The big news this week comes from the Fed, which announced two things. One, it hiked the Fed Funds rate another 25 basis points. The target is now 1.00 to 1.25%, and there will be further increases this year. Two, the Fed to reduce its balance sheet, its portfolio of bonds. It won’t do this by actually selling, but by not reinvesting some of the principle repaid as the Treasury rolls over each bond at maturity. This is like reducing the workforce by a hiring freeze and attrition, rather than by layoffs.

We are no Fed insiders, but if we were to take an educated guess, we would read the last part as a shuffle between the Fed and the banks. No one can afford rising long-term bond yields, as the banks hold plenty of them and this would be a capital loss. Also, if bond prices drop then all other asset prices would drop too. Banks would take another hit.

Right now, the banks are lending to the Fed at 1.25%. The Fed uses this cash to finance its purchase of long Treasury bonds. The 10-year bond closed on Friday at a yield of 2.16%. If the Fed can arrange for the banks to swap, basically slowly draw down their excess reserves and buy the bonds, then it would not cause the bond market to crash. At the same time, the Fed can say that it has shrunken its balance sheet. There would be no change in the bond market, but the banks can bypass the Fed, while increasing their net interest by about 0.9%.

This move would have one nonobvious side effect. The duration risk moves from the Fed to the banks. This is the risk of capital loss, if the interest rate should move upwards. At least the risk moves to the banks nominally. In practice, the Fed will have to bail out the banks should they get hit by this (or assure the banks that the Fed will do everything it can to prevent long bond yields from rising).

We present the issue in these terms, because bank solvency (and the Fed’s own solvency) is the real motivation of the Fed. Price stability—defined to make Orwell proud, as rising prices of 2% per year—is not occurring right now. That is, the Fed has failed to stimulate the price increases that it wishes.

And the Yellen Fed does wish for rising prices. In a key paper she wrote in 1990 with her husband George Ackerlof, Yellen presented her theory of inflation and the labor market. Let’s strip the academic regalia, to see it in plain terms.

- Disgruntled employees don’t work hard, and may even sabotage machinery.

- So companies must overpay to keep them from slacking.

- Higher pay per worker means fewer workers, because companies have a finite budget. Yellen concludes—you guessed it:

- Inflation provides corporations with more money to hire more people.

It’s not much as a theory of labor, but does rationalize money printing rather neatly.

The mainstream belief held by Yellen, along with her most trenchant critics, is that rising quantity of money causes rising prices. Never mind that it has failed to work out that way since the Fed turned on the printing press afterburners in 2008. It remains the prevailing belief. So it is somewhat amazing that, with consumer prices falling short of the Fed’s official policy goal of 2% per annum, the Fed is decelerating.

Maybe, Yellen feels that jawboning—saying the economy is getting stronger, etc.—will be more effective than another round of quantitative easing. Maybe. The Keynesians have a cherished belief that so called animal spirits animate markets (and Yellen is a member of the New Keynesian School).

Or, it could be that banks are getting strangled. Banks don’t care about unemployment, nor about consumer prices. They don’t even care about the dollar, being both long and short. That is, they are both borrowers and lenders. They borrow short to lend long.

While the short-term rate has been rising, the long-term rate is back to falling again (which has been the trend since 1981). The effect on banks is: margin compression. The banks are choking, for lack of net revenue oxygen. They will breathe a bit easier if they can make 2.16% rather than the 1.25% as now.

What does this have to do with inflation? Another news item this week illustrates. Amazon bought Whole Foods. Amazon has unlimited access to credit through the bond and stock markets. The lower the interest rate, the more access the big corporations have, to dirtier cheaper credit. They can’t necessarily use this credit to grow their real businesses (one cause and also effect of it being so cheap) but they can use it to make acquisitions. Acquisitions that would not be economic at higher rates.

What will Amazon do with Whole Foods? We would guess that they will pursue Jeff Bezos’ stated vision for the future: that people will always want faster delivery and lower prices. Amazon will use its superior information technology, logistics, scale—and dirt cheap credit—to drive down costs, prices, and margins at Whole Foods. And all other grocers will likely have to follow suit.

So much for higher prices. An expansion of the credit supply (the dollar is not money, which would be gold) is supposed to stoke higher prices, and here is a case where it causes lower prices.

By the way, lest anyone think that this is good because consumers get lower prices, it’s not. Sure, consumers benefit for now. But the real damage comes from the fact that the whole process is fueled by burning investor capital. That is the real nature of too-cheap credit.

And this right here is the indictment of the dollar. Not rising prices, skyrocketing prices, or hyperinflation. At least not now nor the foreseeable future. Falling interest, capital consumption, wage pressures, and unfair advantages handed to crony corporations. All managed by a Fed Chair with a frivolous theory on inflation who knows not what she does.

What does this have to do with the price of gold? Well, the price jumped up early on Wednesday as weak retail sales and inflation data numbers came out. But when Yellen spoke, the gold price fell back down, giving back the whole move and then some.

Which is all just noise. Speculators gonna speculate, but the fundamentals of gold supply and demand do not change with an inflation data report or a Fed Chair monetary policy announcement.

Over time, if people perceive gold as an inflation hedge, and continue to see a lack of inflation, maybe they won’t buy gold or even sell it. If so, they are betting on the dollar as it continues on in its ultra-low interest rate (and long-term falling) environment.

We will take a look at the Wednesday intraday gold basis overlaid with the gold price, below.

…

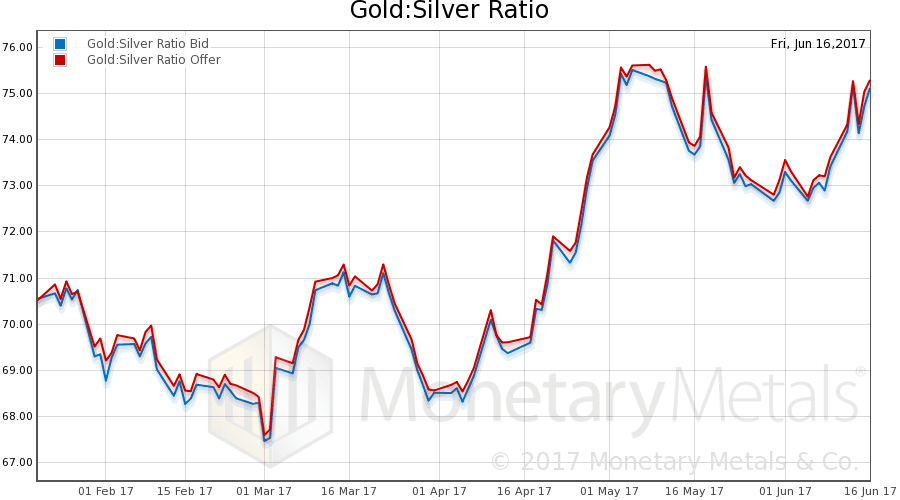

This week, the prices of the metals fell. Gold went down about $13, and silver about 50 cents. As always, we are interested in the supply and demand fundamentals. But first charts of their prices and the gold-silver ratio.

Next, this is a graph of the gold price measured in silver, otherwise known as the gold to silver ratio. It moved up a sharply.

In this graph, we show both bid and offer prices. If you were to sell gold on the bid and buy silver at the ask, that is the lower bid price. Conversely, if you sold silver on the bid and bought gold at the offer, that is the higher offer price.

For each metal, we will look at a graph of the basis and cobasis overlaid with the price of the dollar in terms of the respective metal. It will make it easier to provide brief commentary. The dollar will be represented in green, the basis in blue and cobasis in red.

Here is the gold graph.

We had a rising price of the dollar (the mirror image of the dropping price of gold). The abundance fell (the basis) and the scarcity increase (the cobasis).

Our gold fundamental price shows an increase of about $10 to $1,334 (see chart here on our website).

Here is the intraday graph of Wednesday (all times are London) showing the gold price overlaid with the August basis.

The basis starts a little over 0.6% and droops along with the price from about $1,266 to $1,265. As the price shoots up $12, the basis shoots up 12bps. Later, the price begins to drop and so does the basis.

While the amount is coincidence, the relationship is not. It is causal. This is what first speculative buying, then speculative selling, looks like. All in one day.

Now let’s look at silver.

In silver terms, the dollar rose more (i.e. the price of silver fell more). The decrease in abundance and increase in scarcity were correspondingly greater.

Our silver fundamental price increased two cents (to $17.54). That gives us a fundamental gold-silver ratio of 76.07 (see chart on our website). Not too far from the close on Friday of 75.12 bid and 75.29 offer.

Monetary Metals will be exhibiting at FreedomFest in Las Vegas in July. If you are an investor and would like a meeting there, please click here.

© 2017 Monetary Metals

:

:

“Our gold fundamental price shows a decrease of about $10 to $1,334.” Did you mean to say “increase”?

Yes, correct, thanks for picking that up, I’ll fix it now.

Great post Keith. One of your best. See you at Freedom Fest!

Amazon’s deal with Whole Foods may not be deflationary. Whole Foods is a little more upscale and doesn’t seem a good start for competing on price. Amazon may not be gunning for margins in the grocery business, but is buying the customer information they will acquire by filtering through all customers’ in-store communications and their behavior (location, how long they pause at the cheese counter, etc). For Google and Facebook, the money is also not in the services they sell, but in advertisement and especially in selling information on their customer base. Amazon wants more of that type of action, because most of its activities aren’t exactly long term profitable.

Great Post Keith. I’ll have to read this a few times. As the Fed sells bonds, banks pay in exchange with excess reserves. So, shouldn’t this reduction of the Fed’s balance sheet have a marginal effect on banks’ ability to expand credit?