Monetary Metals Gold Outlook 2021

This is our annual analysis of the gold and silver markets. We look at the market players, dynamics, fallacies, drivers, and finally give our predictions for the prices of the metals over the coming year.

Introduction

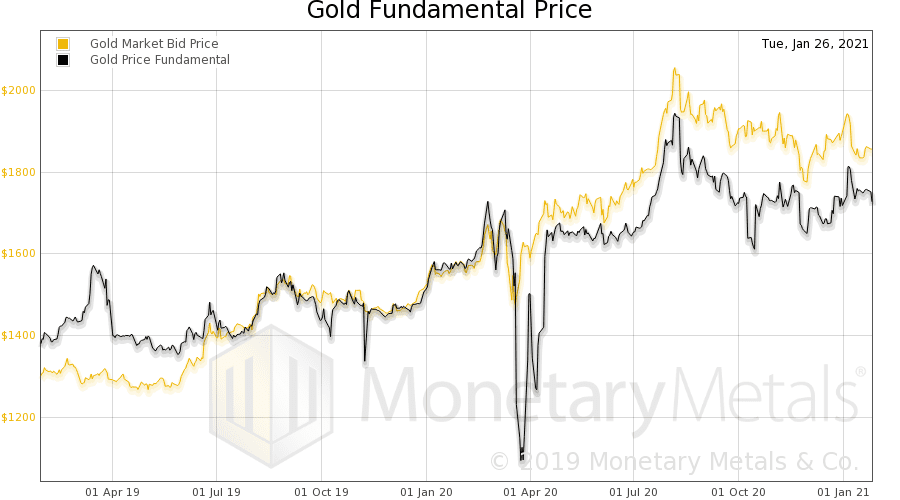

Predicting the likely path of the prices of the metals in the near term is easy. Just look at the fundamentals. We calculate the gold fundamental price and the silver fundamental price (methodology described below) every day, and our data series goes back to 1996. Here is a graph showing the gold fundamental for three years.

Last year, with the price of gold around $1,575 our call was:

“We believe it is likely that gold will trade over $1,650 during 2020. We would not bet against it trading higher, perhaps much higher.”

As it turned out, the price briefly spiked over $2,000. Of course, that was the initial reaction of the market to the Covid lockdown. We did not predict Covid, but the fundamentals were pointing to a higher price. After the initial spike, the price subsided to a new level that is about $200 over our call.

A year ago, and with the price of silver around $18.30, we called for silver to hit $23.50 and a gold-silver ratio of 70. The price is now well over that, and the ratio is well below 70.

These calls weren’t bad, considering that for the long years after 2011 we got a reputation for being “permabears”.

Of course, the market price can diverge from the fundamental price, sometimes by a sizeable percentage and sometimes for a long period of time. And it tends to converge again, sooner or later. Right now, the market and the fundamental prices are $130 apart.

Since the Covid lockdown, the gold and especially silver basis have been reading artificially high (and thus their fundamental prices are too low). Because of logistics problems in delivering gold in the carry arbitrage, and because market makers are pulling out of the market, the high basis does not indicate high abundance of the metal. So we will not dwell further on our calculated fundamental price.

Anyways, to predict the price over the longer term, one cannot focus on the current basis too much. The basis shows the relative pressures in the spot and futures markets, but only a snapshot. It does not predict how those pressures might change. For that, one looks at the dollar of course, credit, interest rates, other currencies, the economy, and even wild cards like bitcoin.

In fourth grade math class, Miss Jennifer didn’t want the kids to just write “42” (with due respect to Douglas Adams). She wants to see the work all written out. It’s not so valuable if we say, “silver to $10” or “$100”, without saying why.

Below, we will show our “long division” work before getting to our bottom line numbers.

How Not to Think about Gold

It may seem odd to begin by discussing how not to do it.

However, there are some very common approaches that are very wrong, including analysis of retail bullion products, price manipulation conspiracy theories, rumors, out-of-context-factoids, or mining production and manufacturing consumption data.

Let’s talk about those for a moment.

At the time of this writing, it’s popular to juxtapose high retail product premiums with the drop in price, on days when the price falls. Advocates of this idea treat it as obvious, like a truck barreling down on you, that retail product premiums are the market. And therefore, if the price drops it proves that there is some kind of nefarious manipulation scheme.

We liken this to the idea that if the price of a mocha latte served in Midtown goes up, that the price of a 37,500 pound lot of coffee in Jakarta must be up. Or, there could be a more prosaic reason: perhaps Covid regulations have tripled the cost that goes into serving a cup of coffee.

Manufacturing capacity for products such as coins is limited and inelastic. If retail demand surges, as it has in the wake of Reddit-related activities, it can pull product out of the distribution channel. But after that, the price of coins has to surge to match demand to the supply.

This does not say anything about the global bullion market, which does not deal in 1-ounce coins. Just as the global coffee market does not deal in cups of mocha latte.

Obviously, persistent (as opposed to a one-day spike) retail demand will pull silver from the global bullion market. But it’s like pulling water from a 1000-gallon tank with a straw.

We have lost track of the number of prominent people who have published a hard date for some catastrophe to occur. These dates have all come and gone—we have been watching this page reschedule Armageddon every six months for years (this year, finally, it says that the offer has “expired”). Some of these guys have predicted dozens of the last zero hyperinflations. But despite their best efforts, the dollar is still intact.

Our view is that the dollar is indeed dying, but it is not via the white-hot thermonuclear blast of hyperinflation. It is by the cold drowning when even a strong swimmer, exhausted, slips below the waves at sea. It is not going to die when “the sheeple wake up,” or due to some meeting of the G20, or a declaration from the IMF or China that the dollar’s reserve status is gone. That is not how it works.

These approaches are unhelpful. They can confuse long-term holders, and cause traders to make costly mistakes.

We have written a lot to debunk claims of price manipulation. Here is our Thoughtful Disagreement with Ted Butler, which has so far not been answered by him or anyone else.

Broadly, conspiracy theories fall into a few categories. One, central banks are selling gold. Maybe, but what explains the even-larger price drop in silver that occurred since 2011? They don’t have any silver. So if gold was manipulated by central bank selling of metal, then silver should show us what a not-manipulated price looks like. And the gold-silver ratio would be closer to 10 than to 100.

Two, banks are short-selling futures naked. This would cause backwardation. It would also cause expiring contracts to move in the opposite direction than they actually do. When each contract expires, someone who is naked short would have to buy it with urgency. If there were really a massive naked short position, there would be a buying frenzy and the expiring contract would be bid up higher relative to the spot price. The basis would rise. The reality—and we show a graph of every expiring contract back to 1996 in our response to Mr. Butler—is the opposite. Falling basis.

Three is just what we have to call magical thinking. For example, the bigger a trader’s position, the more he controls the price. How’s that supposed to work?

We would put rumors, Indian gold import numbers, and news into the same non-predictor bucket. Even when factual, these items are the investing world’s equivalent of an attractive nuisance—they can lure you to financial harm. Most importantly, one should never trade based on what the Fed has done (increase the quantity of dollars) is doing (increase it) or will do (increase it some more). That is not what drives the gold price.

Finally, we come to the numbers for electronics and jewelry consumption, and mine production. We firmly insist that gold and silver cannot be understood by looking at small changes in production or consumption. The monetary metals cannot be understood by conventional commodity analysis.

This is because virtually all of the gold ever mined in human history is still in human hands (to a lesser extent for silver). No other commodity comes even remotely close. The World Gold Council estimated the total gold stocks at 188,538 metric tons at the end of 2017. We believe this understates the reality, perhaps by a large multiple. People have been hiding gold from their acquisitive governments and nosy neighbors for thousands of years. Gold has always been the sort of thing that most people would rather keep quiet about. It defies any systematic inventorying process.

In any case, annual production is a tiny fraction of even this conservative number. The World Gold Council reported annual mine production has averaged 3,247 tonnes over the past three years. This is just 1.7% of then-existing stocks. In other words, it would take 58 years at current production levels just to produce the same amount of gold as is now stockpiled. In regular commodities, this same ratio—stocks to flows—is measured in months. We just don’t hoard wheat and oil for the long term, for obvious reasons. Nor even iron or lumber or other durable materials.

If total gold mining is 1.7% of gold inventories, then small changes within that 1.7% are not likely to have much impact on the gold price.

How We Think About Gold

The implications of this are extraordinary.

All of that stockpiled gold represents potential supply, under the right market conditions and at the right price. Conversely—unlike ordinary commodities—virtually everyone on the planet represents potential demand. If someone offered to pay you 1,000 barrels of oil, where would you put it? The same value of gold could easily fit in your pocket.

A change in the desire to hoard or dishoard gold, even a small one, can have a big impact on price.

There is no such thing as a glut in gold. Over thousands of years, the market has been absorbing whatever the miners put out. Gold mining does not collapse the gold price, as oil drilling or copper mining does, when inventories accumulate.

The whole point of gold is that inventories have been accumulating at least since the time of the ancient Egyptian Empire.

Why would people be willing—not just today, in the wake of the great financial crisis of 2008 and unconventional central bank response, but for thousands of years—go on accumulating gold and silver?

There is only one conceivable answer. It’s because these metals are money. Compare gold to oil. The marginal utility of oil—the value one places on the next barrel compared to the previous—declines rapidly. For oil, it falls rapidly because once your tank is full, you have that storage problem. Assuming you even directly use oil at all (and unless you are an oil refinery, you don’t).

People are happy to accept the 1,001st ounce of gold, on the same terms as the 1,000th or the 1st ounce. It doesn’t hurt that you could carry those 1000 ounces in a backpack, nor that you can find a ready market for it anywhere in the world, from London to Lisbon to Lagos to LA to Lima to Laos.

So if gold is money, then what’s the dollar? The dollar is a small slice of the US government’s debt. It is a promise to pay, though it comes with a disclaimer that says the promise will never be honored. The dollar is credit, whose quality is falling.

This turns our discussion of the gold price inside out.

The Paradigm Shift

We don’t look at it as most people do, that gold is worth $1,800. This is backwards, upside down, and inside out. It is like saying your meter stick is 143 gummy bears long. Instead, we insist that the dollar is worth 17.3 milligrams of gold. This is not merely semantics. It is a paradigm shift—easy to say, but harder to get your head around. The advantage of this perspective is that you can see the market much more clearly.

If you are in a rowboat, tossing about in stormy seas, would you say the lighthouse is going up and down? If you have rubbery gummy bears would you use them to measure a steel meter stick? Can you say that the steel is getting longer, as the gelatinous candy compresses? No, the lighthouse and steel are stable, while the waves and rubber band are not.

When you say “gold is going up”, you can’t help but think you are making a profit. But if you say “the dollar is dropping” then you realize the truth.

Sure, the gold owner may have more dollars, but those dollars are worth less than they were. He should not be so tempted to spend down his gold savings, merely because the value of the dollar fell. The idea of spending one’s capital, of consuming one’s wealth, is a persistent theme across our writings.

You cannot profit merely by holding gold. You can avoid losses (which is a good thing, of course). But avoiding a loss is not the same thing as making a gain.

We go further. We advocate that everyone calculates his net worth in gold, and measure profit or loss based on gains or losses in gold ounces. If you had 100oz and later you have 110oz, then you got richer. If you went down to 99oz—even if the price of gold is higher, and your reduced gold is worth more dollars—you have suffered a loss. We encourage you to get into the discipline of dividing your dollar net worth amount by the then-current price of gold. Keep a record and track it every month or every quarter.

You can profit from holding silver, when silver goes up. We don’t mean its price in dollars, but in gold. For example, if the silver price begins at 400mg gold and it rises to 600mg, then you have made a profit of 200mg or 50%. It is about 250mg right now, and it was last at 600mg in 2012.

You can sometimes profit by going long the dollar. It is declining in a century-long downtrend, but that doesn’t mean there aren’t corrections along the way. For example, the dollar hit a low of 16mg gold in 2011. After that, its rally was impressive.

At other times, you can profit by shorting the dollar with leverage, for example buying gold futures on margin. Suppose you have 100oz gold, or about $180,000 today. You need $11,000 cash to have a futures contract position. $180,000 would enable you to buy 16 100oz contracts. In other words, futures offer 16:1 leverage. If the price of gold goes up $54, or 3%, then you profit $86,400 or 48oz gold. Not bad on a bet of 100oz, though of course the risk is extreme with leverage this extreme.

As they say on those shows on TV when they blow up stuff with high explosives, “now kids, don’t try this at home”.

How We Analyze the Gold Market

We think of the market as the coming together of 5 different primary groups.

- Buyers of metal. The end buyers (not intermediaries, e.g. jewelry manufacturers who make the gold products for the hoarders) are typically hoarders. So there is no particular price that is necessarily too high, other than whatever they think is a fair price at any given moment. The demand for gold for hoarding is monetary reservation demand. Their idea of the fair price changes with market conditions, Federal Reserve announcements, monetary policy, etc.

- Sellers of metal. They are dishoarding, for whatever reason. They may think the price has hit a high enough level to attract their greed, or a low enough level to activate their fear. Miners are a subcategory of sellers, though miners are price takers (and a small fraction of the supply in any case).

- Buyers of paper (e.g. futures). These are speculators, with three key differences from buyers of metal. One, they use leverage. Two (for that reason and others), they have a short time horizon. Three, they trade for dollar gains.

- Short sellers of paper. Not nearly so big a group as popularly imagined, there are people who take the two lopsided risks of (1) shorting something with limited profit and unlimited loss potential and (2) fighting a 100-year trend. These people are nimble and aggressive and certainly their trades are short-term.

- Warehousemen, aka market makers. If few people are willing to bet on a rising dollar (i.e. falling gold price), then who sells gold futures? Aren’t futures a zero-sum game, with a short for every long? Enter, the warehouseman. He stands ready to carry gold for anyone who wants future delivery. If you buy a future, you are signaling that you want gold, not to be delivered now, but at some date in the future. For a profit, the market maker will sell it to you. How does he do that? He buys metal in the spot market and simultaneously sells a contract for future delivery. He doesn’t care at all about price, as he has no exposure to price. He responds to spread. Suppose he could buy gold in the spot market for $1,800 and sell it for December delivery for $1,836. That is a 2% profit, not unattractive in this market.

It’s important to keep in mind that virtually all of the gold ever mined is in someone’s hoard. Again, there is no such thing as a glut or shortage. However, the market can experience relative abundance and scarcity and the spreads of the warehouseman provide a good signal to see it.

If there is a big spread between spot and futures—called the basis—then this means two things. One, speculators are bidding up futures contracts. And two, the marginal use of gold is to go into the warehouse. This is a sign that gold is abundant to the market.

Normally, the price in the futures market is higher than the price in the spot market. This is called contango. Contango means it is profitable to carry the metal, which is to buy a metal bar and sell a future against it. However, the basis spread can invert—and it has many times since the crisis of 2008. When it is inverted—called backwardation—it is profitable to sell metal and buy a future. Such decarrying is, by conventional standards, risk free (it’s not, see below). It should never happen in gold, as it is a sign of shortage and there is no such thing as a shortage in a metal which has been hoarded for millennia. Backwardation is a signal to the warehouseman to empty out the warehouse.

In backwardation, the marginal supply of metal is coming from the warehouse (carry trades are unwinding). Obviously, there is only a finite supply of gold held in carry. Thus, backwardation presages rising price.

This is the only way to analyze supply and demand fundamentals for the monetary metals. They are not consumed, and only accumulate over time. They have a stocks to flows ratio (i.e. inventory divided by annual mine output) measured in decades. As they’re not bought to consume, there is no particular price ceiling.

The five market participants interact to form a constantly changing dynamic. It is this dynamic that we study when we look at spreads between spot and futures, and changes to these spreads. Monetary Metals has developed a proprietary model based on this theory, which outputs the Fundamental Price for each metal. This is updated every day.

We have published more on the theory.

Macroeconomic Conditions

Last year, we wrote:

“As of the last writing of this annual market outlook, it was common belief that we are in for a period of rising prices and interest rates. We didn’t agree then, and we don’t agree now. The idea of rising rates is a bit less popular, now that the Fed has reversed itself and (so far) cut the effective Fed Funds rate by 80bps.”

And just like that—with the interest rate much lower than in 2018—this idea is now quite popular again. Indeed, one would be hard pressed to find anyone who doesn’t think rates will rise from here, along with consumer prices.

The mainstream view holds that bond buyers will demand higher rates as compensate for the loss of purchasing power that will come from the mass quantities of money printing.

The only problems with this view are: (1) the bond buyers may have a desire for higher rates, but Roosevelt’s move in 1933 has disenfranchised them, (2) one cannot compare interest rates to falling purchasing power, (3) if prices are rising, they are rising due to regulatory forces (i.e. mandated useless ingredients) and supply destruction in the wake of Covid, (4) the Fed is borrowing to finance its bond portfolio, not printing.

In his theory of interest and prices, Keith Weiner describes the falling interest rate environment that began in 1981 when interest rates were above the productivity of the marginal entrepreneur. With each downtick in the rate, the incentive to borrow more becomes greater. Businesses borrow to add capacity. That is, hamburger restaurants add hamburger supply, pencil manufacturers add pencil supply, automakers add car supply, and farmers add wheat supply. If supply is added—not in response to rising demand—but in response to falling interest, then it must cause prices to fall.

However, it should be noted that rising useless ingredients is a force in the opposite direction. The net result may be prices do not fall, or do not fall by much. There are two differences between this case and when rising interest rates drives ever-higher prices. One, profit margins are under pressure. Two, prices are soft. The cost to deliver the goods may be rising, but consumer demand does not match it. The present environment is nothing like the 1970’s.

At the same time as the number of dollars of debt is rising exponentially, the net present value of each dollar of that debt is rising. NPV of a dollar of debt doubles with each halving of the interest rate.

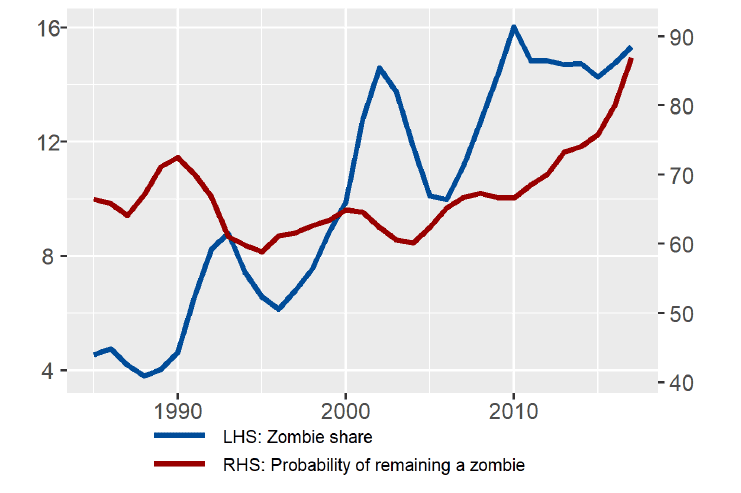

The Bank for International Settlements publishes research on the debt of zombie corporations. BIS defines zombie as a company whose profits are less than interest expense (and recently added some other stipulations). In other words, a zombie survives only by grace of ultra-low rates and ultra-loose credit markets. Here is a graph published in the latest BIS report on Zombies.

BIS Working Papers No 882, Corporate zombies: Anatomy and life cycle by Ryan Banerjee and Boris Hofmann

This is a clear demonstration that interest is above productivity for marginal firms. And the margin is no thin line for a few outcast losers, but a big chunk of the market. Currently about 15%. And note that BIS estimates their odds of remaining a zombie (i.e. not recovering) to be nearly 90%.

So what happens if the Fed tries to raise rates? It should be obvious, even to the dirigistes, that the zombies will collapse. Their employees will be laid off, putting them under pressure to default on their own creditors. And reducing their spending on everything from pizza to petrol. Which reduces revenues to firms which are not currently counted as zombies.

Rising rates is also the inverse of falling asset prices starting with the bond. The so-called wealth effect is put into reverse. If people spend more as they keep making capital gains and profitable trades, what happens when their portfolios shrink? They buy less, if not pizza, then Porsches and pinot noir.

If falling rates incentivize companies to borrow to buy their own shares, and in some cases to pay dividends, what happens when rates rise?

The environment of the past four decades is a damning indictment of the regime of central banks, their irredeemable currency, and central planning generally.

Credit demand is only generated with a downtick of the interest rate.

Profit margins are soft but if the cost of borrowing goes down, then there is a business case to open that next store, to develop that next strip mall, etc. If the cost of borrowing were to go up, then the game would be over.

In this Covid lockdown economy, commercial real estate is under stress. Even here in affluent Scottsdale, the major indoor mall has vacant spaces. Every strip mall has empty storefronts. Those restaurants which are still in business are struggling even to fill the 50% capacity allowed by law. The building where we have our office has several major corporate tenants, but those offices have been vacant since lockdown began almost a year ago.

Yet developers are building more retail, restaurant, and office space! Something tells us these developers aren’t stupid. They will fill their glorious new buildings—with tenants poached from older shabbier buildings. And at the lower rents that they can accept, thanks to lower interest rates.

A year ago, we wrote that 6-month LIBOR was 1.87%. Now even the 10-year is about half of that, and 6-month LIBOR is around 0.2% (lower, even, than in 2014 before Fed Chair Janet Yellen’s abortive rate-hiking episode).

Her rate hikes were a big increase in cost for business borrowers (to say nothing of governments). For every $1,000,000 financed in 2014, the annual cost of interest was $3,200 a year. She pushed it up to $28,000. Now it is around $2,200.

One further proof point that the demand for credit falls off a cliff if rates rise is the curious case of the automakers’ subsidized financing. All through the abortive rate-hike episode, they kept offering 0% for 72 months. Rising rates gave them a bitter choice: either eat the additional costs or else pass the cost on to consumers and sell fewer cars. They ate the cost. Perhaps they needed to sell those cars to generate the revenues to pay the interest expense on the debt they previously incurred to expand the capacity of their factories.

The Federal Reserve does not have control over the interest rate on the long bond the way it has over the short end. This has particular poignancy to the banks. The banks borrow short to lend long. They profit from the spread between LIBOR and 10-year Treasurys.

At the time that LIBOR was 0.32%, the 10-year Treasury was 2.2%. Banks were raking almost 2% from this trade. Today, the Treasury yields 1.1%, with 6-month LIBOR at 0.2%. Banks today can earn a small spread (though they need leverage to make enough to stay alive). This is now better for them than at any time since Covid and the lockdown. At the start, the 10-year bond yielded only around 0.5%.

We are headed back down to 0.5% and beyond (just look at Switzerland, the Euro zone, the UK, and Japan for a roadmap).

Falling interest is enormously destructive. We are not proposing a monetary policy of continuing to cut rates. Or indeed any monetary police. There is no right central plan. We are simply saying that the Fed is boxed into a corner by its own past bad policies. We don’t think it wants a repeat of 2008, and it won’t, so long as it has a way to postpone the reckoning. Even if the very postponement makes the inevitable reckoning worse in the end.

Falling rates creates massive capital gains for bond holders, and the rising bond price is propagated to other markets. These gains are not from rising productivity. They are from monetary policy, which cannot create wealth but merely the illusion of it, i.e. the so-called wealth effect. The wealth effect is not wealth, the way pasteurized, homogenized whipped cheese in a spray can is not cheese.

These capital gains for bond holders come at the expense of bond issuers, who are, in essence, short their own bonds. If you short something and it goes up, you incur losses (we acknowledge that this is not recognized in current accounting practice).

We will talk about rising vs. falling interest rates and its impact on the price of gold below.

Not the Drivers of the Big Price Move

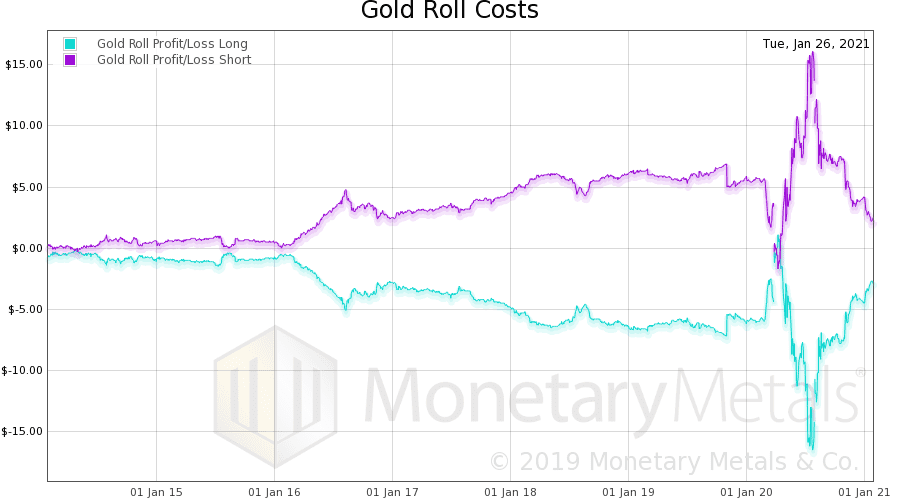

Speculators view gold and especially silver as just a vehicle to ride, to make more dollars. They can pull the price pretty far, at least for a while. Like stretching a big rubber band. However, it gets exhausting to keep up the force. Eventually, if they’ve gotten the trend wrong, they must let go. At some point, fatigue sets in (not to mention the cost of the keeping and rolling a futures position). Here is a graph of the cost of rolling a futures contract, showing seven years.

For long positions, look at the cyan line which is negative. For quite a while, it cost almost nothing to roll each futures contract, around 50 cents. The cost went up quite a lot, but has recently come down again. It is now around $3. A speculator had better expect a decent price move, to be willing to pay that cost at each contract roll (six times a year).

Many in the gold community expect big price gains in gold. So they don’t think of the cost of carry. But most people don’t like to pay to carry an investment. Monetary Metals is getting rid of the cost of owning gold, and instead making it pay.

If you want a durable move, it will not be driven by people who spend about $25 per ounce per year to hold their betting position. It must be people who change their preference from holding the government’s official money to holding money in fact.

Next let’s move on to inflation, so called.

We said it in Outlook reports years ago, and we reiterate now: we would not put capital in harm’s way betting on the thesis that inflation is going to jump up, and that this will cause the gold price to jump up.

For one thing, commodities continue their falling trend. And car manufacturers offer 0% for six or seven years (we are once again seeing ads for 0% for 84 months) as a desperate attempt to stimulate sales. What kind of inflation is this? Car manufacturers have no pricing power.

Do not cite the rising cost of meat in a lockdown world where plants have been shut, and vast herds had to be destroyed (or now, in China, there is another disease ravaging pigs). This is nonmonetary.

It also has nothing to do with the price of gold. There is no reason to expect the price of gold to go up every time a local regulator increases the cost of producing products included in the consumer price index.

Inflation

Milton Friedman famously declared that “inflation is everywhere and always a monetary phenomenon.” But we have written about the concept of useless ingredients: when the government mandates that companies add something to their product or production process that consumers do not know about and do not care. For example, gasoline must have a certain amount of ethanol or MBTE added. This drives up the cost, and hence the price.

Per Friedman’s nostrum, this is lumped in with all the other upward price pressures. Meanwhile, there is also downward pressure. One source of downward pressure is improving efficiency. Another is falling interest rates.

Upward forces are netted against downward forces, and the result is the inflation statistic for the year. Everyone knows that ethanol makes gasoline more expensive, but this fact is forgotten in discussions of inflation. And people turn to the Fed to respond to this somehow. What is the Fed supposed to do about the cost of ethanol mandates?

In 2020, a new force for higher prices hit the market like a shotgun blast. Government lockdown policies disrupted supply chains, and in the case of meat packing plants in the US, outright destroyed production capacity and hence supply. What happens when supply is reduced and demand is relatively inelastic?

The price of meat skyrocketed.

Other government policies—most notably tariffs—have the obvious effect of causing certain prices to rise. So far, the new Biden administration does not seem to be interested in reversing any of these supply-reducing policies. Instead, they are looking to reduce the supply of oil, for example. And to force up the price of unskilled labor.

The great Heavyweight Bout of the ‘20s will be:

Falling Interest vs. Supply Destruction

Let’s get one thing out of the way first. In markets where supply is not destroyed, and imports are not a significant source of product, prices will fall.

Second, in low-margin products like gasoline, the price at retail will go up dollar for dollar with whatever costs are added due to government policy such as a hike in the gas tax or shutting off supply from shale.

These are the two obvious calls. In many markets, there will be a more even balance between government attempts to force prices up and the Fed’s attempt to force prices down (via forcing interest rates down, which the Fed does not realize causes prices to fall). We will have to watch the action, blow by blow, to make a call. We may see more of what occurred in 2020, that is rising price of meat along with falling price of clothing.

And this brings up another important point. The government can destroy demand, too. When people do not go to work in offices, they do not need to wear business attire. When large gatherings for weddings are outlawed, people do not need to dress up. We don’t have the statistics, but surely the number of formal suits sold in 2020 was massively down compared to 2019.

This means that even if the government destroyed some formalwear supply, the price could be down due to greater destruction of demand. And this balance is different in each market. Alcohol comes to mind. With bars closed, people may drink less. Or with their futures destroyed, people may turn more heavily to drink. And within the alcohol category, there could be a drop in the kind of products that are popular in bars, while at the same time there is an increase in the stuff preferred by people who drown their sorrows at home.

Oil supply may be reduced, but with people not commuting to work, gasoline demand may be down even more.

One thing is clear. Gold is not debased or debase-able. So if there is a general dollar debasement, owning gold is the way to protect yourself from its ravages. To avoid the loss imposed on dollar holders.

However, things get rather more complicated if one tries to measure dollar debasement using consumer prices. Consumer prices are a weak proxy for dollar debasement, like traffic collisions are a weak proxy for speed or movie theater revenues is a weak proxy for the average amount of time people spend being entertained.

If the price of meat at supermarkets goes up because the regulators shut down meat packing plants (while the price of live cattle crashes, and ranchers are forced to destroy whole herds) then do not expect this to cause the price of gold to go up.

Loss of the Dollar’s Reserve Status

This is a perennial theme. It comes up every so often, and right now it seems to be making a new surge in popularity. In essence, it confuses a few things.

One, what currency is used to pay for goods bought by one party and sold by another party. For example, China may try to foist off its yuan to pay for oil. If the world demand for oil is collapsing (perhaps due to people not commuting to work), and supply is robust (perhaps due to falling interest rates), they may find a seller of oil who can be strongarmed into it.

However, what China cannot control is the currency preference of the seller for holding. All major currencies trade in liquid markets. If you want dollars and someone pays you the yuan equivalent of $1 million, you can trade the yuan for $1 million. You lose only the bid-ask spread.

What would influence the oil producer’s preference for dollars over yuan? Obviously, if it expects that sellers of the things it needs (including labor, engineering contractors, tooling, motors, etc.) will want dollars, it will tend to prefer to hold dollars. This is especially so if it has long-term contracts denominated in dollars.

The elephant in the room is debt. If the oil producer owes a billion dollars, this gives it a strong preference for dollar revenues and holding dollars. That is, it will price its oil in dollars. It will say “pay us $1 million in USD or equivalent.” If the seller wants to pay a million bucks worth of whatever amount of yuan—or bitcoin—that trade for a million bucks at the time of the transaction, then that’s OK. The seller will just exchange immediately for the one million dollars it needs.

And notice that the dollar is on both sides of this hypothetical oil producer’s balance sheet. It owes dollars (liability) and prefers to hold dollars (asset).

The balance sheet is not so easy to change. And there is something that is even harder to change: millions of balance sheets. This is the network effect. Every website uses HTML because every web browser can read it. Every browser can read HTML because every website uses it. These kinds of things tend not to change.

Speaking of China and the dollar as reserve currency, two things must be mentioned. One, the People’s Bank of China holds about a trillion dollars of US Treasurys. There is no other currency that could support the inflows, if China were to decide to sell its dollar holdings and buy an alternative. The only thing that it could do is incur dreadful losses.

Two, the people in China want to get their money out of the yuan. The government fears what would happen to the value of the yuan if it allowed such lopsided selling pressure. So it imposes capital controls. And the people find ways to evade them (even risking dreadful punishment, so strong is their desire to escape the yuan). And the government ratchets up the controls, and the people find more creative ways through. The point is that if there were a candidate for a currency to surpass the dollar as reserve currency—it’s hard to imagine it would be a currency that the natives have to be forced to hold under dire threats.

The attraction of the loss-of-reserve-status story to the gold community is that if the dollar were to lose its status, then the price of gold—as measured in dollars—would skyrocket. This is kind of like saying that if a rock falls over the edge of a cliff, then the top of the cliff would rise rapidly. At least if you had a measuring instrument attached to the falling rock. Maybe the top of the cliff is soon 100 meters higher than the rock. And maybe the ounce of gold is suddenly $100,000 higher than the falling dollar. But is that a gain of altitude for the cliff-top or a gain in value for gold?

Reset Gold/Dollar

Closely related to the idea of loss of the dollar’s reserve status, is the idea of a “reset”, so called, of the gold price or the dollar (these two are inverse to one another). No one party has made the dollar the reserve asset. It is the reserve asset because of millions of choices, made by the managers of millions of balance sheets from central banks to commercial banks to insurers, pension funds, corporations, businesses, and individuals all over the world.

And no one sets the price of gold/dollar either. Therefore no one has the power to reset it.

Whenever we say this, a reset proponent inevitably says “in 1933, FDR reset gold from $20 to $35.” This shows a fundamental confusion. The world prior to 1933 was quite different. There was not a price of gold per se. One did not buy gold per se.

From before the Founding of America, until FDR in 1933, a paper bank note was evidence of money—i.e. gold—deposited. People redeemed the paper to get back their gold. $20 was not a price. It was a standardized unit of the deposit contract, saying that one deposited gold at a rate of (approximately) one ounce to twenty dollars. Resetting gold meant a partial default on the sacred obligation to return your gold.

Today, no paper Federal Reserve Notes came into existence as deposits of gold. And no paper note carries the right to demand redemption in gold. If you want gold, you must find someone who has it and who wants your paper. Tomorrow, the exchange rate may change.

The government cannot do today what it did in 1933, because gold is not part of the banking system. The most they could try to do is declare a price-fixing scheme. Aside from the fact that they don’t care about gold enough to bother, it would be guaranteed to fail.

Every price-fixing edict in history has failed.

Bitcoin

With bitcoin hitting a price well over $40,000 no analysis of gold would be complete without addressing a few key questions. One, does the high and rising bitcoin price tell us anything about the likely direction of gold?

Some people say that bitcoin is “taking over” gold’s role. That as money flows into bitcoin, that means it is flowing out of gold. This is not even wrong (to borrow a phrase from physicist Wolfgang Pauli). It’s not money, it’s dollars. And anyways, the dollar does not go into anything. The dollars stay in the banking system. The seller gets the dollars, and the buyer gives up the dollars to get the bitcoin. The dollars are not consumed in the transaction; the seller can exchange them for something else, and that seller can exchange them for another thing including bitcoin. Or gold. There is no limit to how high a price can be bid up, even if the quantity of dollars is not changing. And no limit to the number of things whose price is bid up, either.

The idea of taking over gold’s role confuses price with function. There is no dispute that bitcoin’s price has risen meteorically. The debate is whether high price or rising price conveys a monetary status. Does a nonmonetary thing become monetary at a certain threshold?

No. People may buzz about it more, as its price rises. And the buzz, make no mistake, is how to use it to make more money! Ironic, to debate if a thing becomes money when its price goes up and more people talk about—how to use it to make money. That is, it’s a popular trade.

There is one way that bitcoin and gold are alike. Both come to mind when people think of the government’s profligate spending, and the Fed’s rising quantity of dollars with falling interest rates. So in a sense, more buzz about bitcoin is more buzz about the failing monetary system and that can lead more people to buy gold. Which drives up the price. Hence, in this sense, bitcoin awareness drives gold awareness.

Monetary Metals

We are referring to our company here, not to promote it, but in the context of our discussion of the price of gold.

Many people have referred to buying gold as a non-expiring call option on a return to a gold standard. Once in a while, something comes along in the news about a policy proposal that could lead to the gold standard, or someone writes a paper about it. And some people buy gold based on their perception of an increase in the odds.

Monetary Metals has issued the first gold bond in 87 years, and has many more coming. When news of the return of gold bonds and the gold interest rate spreads more widely, it is possible that this will be perceived as a more credible path to remonetizing gold. And for every one investor who buys a gold bond there could be a thousand who buy gold itself.

This effect will obviously be small at first, and grow with the number and size of the gold bonds issued. We would not expect it to affect the price of gold in 2021, but we would not rule it out either. In 2022, it may get more interesting.

Be Careful What You Wish For

Many gold speculators would love the gold price to rise rapidly to $5,000 or more (we saw one gold dealer touting $65,000 in a talk at a conference). We would first like to point out $5,000 means the dollar drops to around 8mg gold. The whole world runs on dollars. Think what will be happening to people, pension funds, insurance, banks, farmers, employers, etc. if the dollar drops by almost two thirds.

It is tempting to look around, see the fat cats driving their Ferraris to skyscraper rooftop bars, wearing Swiss watches and Italian suits, and think “If only gold goes to $5,000 or $10,000, then that will be me.”

We don’t think so. If the price action happens slowly, say over 10 years, it will represent a steady erosion of the world’s capital base. Holding gold will keep you (mostly) safe from that erosion, but will not make you rich.

If it happens rapidly, it will be something else entirely. The collapse of 2008 was ugly, until central banks put it on pause. They agreed to an unfathomable Faustian deal with the devil. When the collapse resumes, it will make 2008 look like a dress rehearsal.

Those rooftop bars will be closed. There may be Ferraris for sale cheap, but with refineries and gas stations failing, getting fuel could be a challenge. Moving dollars out of your bank account to buy the fuel could also be a problem. The mood on the street will be ugly, and few people will dare flaunt their Ferraris openly. Even today, in relative calm, many municipalities are having a hard time keeping up vital services such as police and fire. They will find it much harder when they can’t keep getting more free money, which they pretend is borrowing (borrowing without means or intent to repay is counterfeiting, monetary fraud).

Something will inevitably happen to remind people that gold is not just for hedging inflation or speculating for dollar gains. To understand, put yourself in the position of a citizen of Cyprus in February 2013. On one Friday afternoon, you had what you thought was a few hundred thousand euros deposited in a bank.

And then, on Monday morning, you didn’t.

It turned out that the Cypriot banks had invested in Greek government bonds. They had long since lost your deposit but continued to operate in a state of insolvency. They eventually got to the point when they could no longer keep up the pretense. People who had their euros locked up in closed banks nervously waited. There were tight limits to withdrawals. And haircuts for depositors—losses shared with other classes of creditors. Virtually everyone on the island was in this vulnerable and terrifying position.

Those few Cypriots who had previously bought gold, found they could easily get on a boat and go to the mainland where conditions were better. We spoke with a gold bullion dealer in Nicosia, Cyprus. He told us that very few had bought gold. Most did not realize their peril (or did not want to see it) until it was too late.

The virtue of owning gold, for Cypriots, was not in the hope its price would rise. In fact, it did not rise at the time. It was more elemental than that. Gold is not someone else’s liability. It is a lump of metal, which means that it cannot default. It is not subject to a negotiation of the International Monetary Fund, the European Central Bank, and the European Commission. Unlike these central planners, gold will not sell you up the river.

If you own it on Friday, you still own it on Monday, and it gives you the freedom to do as you please.

Events are coming that will remind people of this. We think these reminders are likely to be very pointed. When hundreds of millions of people in Europe, South America, and even North America eventually, wake up one day to the reality of losses on what they had assumed was money safely in the bank, the buying pressure in gold and silver will be truly ferocious. Notably, the selling will not be comparable. There will be some fools who are eager to book their illusory profits as the price rises. But most won’t trade their metal for bank deposits of unknown provenance and unknowable risks.

We will come to a time of exponentially rising price combined with exponentially rising backwardation. That is, the gold futures market will cease to work.

It will be a time of woe, though a bit less horrible for those who own gold compared to everyone else. Not a time of 100th floor rooftop bars, $50 cocktails, and jetting off to London for the weekend.

We emphasize that the endgame of the dollar is not imminent. We will continue to update the picture as events inexorably play out.

In 2015, we published an article about the coming collapse of the Swiss franc. We were early (though we did not say the collapse was necessarily coming in 2015). This collapse, when it comes, will shake up the monetary system. The yield on Swiss bonds is negative for all durations.

How Not to Predict the Gold Price

In the Outlook 2016, we addressed the belief that the money supply (i.e. quantity of dollars) drives the price of gold. Short answer: it doesn’t. In Outlook 2018, we showed that interest rates are not correlated with the price of gold.

Both of these ideas are very popular. If you think about it, the first one is obviously wrong. The Fed is always increasing the quantity of what it calls money. The gold price goes up, sideways, and down. The second just does not work either. The price of gold shot up during the period of rising interest rates in the 1970’s. Since 1981, the interest rate has been falling. During that time, the price of gold has gone up, sideways, and down.

These supposed correlations just don’t work.

That said, there is a connection between interest and gold. It’s just not a simple correlation. We will address that below.

First, we want to comment on two things that have many buzzing today. One, the fall of the dollar cannot be measured in euros, pounds, yuan, etc. These currencies are dollar-derivatives! When they go up, it does not indicate the dollar is going down. It indicates that the risk-on trade is back on. It indicates a boom, where market participants are borrowing dollars to exchange for other currencies to buy assets denominated in those currencies. This can either be to profit from a higher interest rate, or in the hopes of capital gains. In other words, the euro or pound is going up.

You cannot infer that because the euro is on a tear, that this means the dollar is going down and therefore gold will go up (just as the dollar cannot be measured in terms of euros, gold cannot be measured in terms of dollars).

What Drives the Gold Price

Excluding speculators, people buy and own gold for the long term because it is money. Nearly all of the gold ever mined in human history is still in human hands.

This is how you’d expect money to behave.

So of course lots and lots of people own some. If we want to try to predict the price, we want to look at change at the margin. Will those who own now have a reason to sell? And will those who do not own it have a reason to buy?

The first question is: why does someone own money? Basically, it’s because he does not want to be a creditor. There are two reasons for this: risk and interest that compensates savers for taking risk. Let’s first look at risk.

To own a paper dollar bill, one is a creditor of the Federal Reserve. If you think that the Fed’s paper is risk free (which it is defined to be by modern finance), then you have no reason to own gold. If you look at the Fed’s balance sheet, and wonder what happens as its cost of funding goes up and at the same time the yield of its portfolio remains flat and the value of assets is declining, then you see risk and hence have a reason to own gold.

To deposit that paper bill in a bank is to add bank credit risk on top of Fed credit risk. Once upon a time, the banks paid interest on deposits. But now, not so much.

An increased awareness of risks in the banking system causes people to buy gold, and hence the price rises.

Now let’s look at payment to creditors, otherwise known as interest. Everyone has a price he demands, in order to give up his money and extend credit. If the interest rate offered to him is below this preference, he will not want to lend.

Central banks have a prime directive: to make it cheaper for the government (and its cronies) to borrow, so it can spend in excess of revenues. It seems such a simple exercise. Just buy government bonds. Push up the price of the bond, and that means the interest rate goes down (rate is a strict mathematical inverse of price). Unfortunately, they set in motion a dynamic system characterized by resonance and positive feedback.

To picture resonance, watch this video of the collapse of the Tacoma Narrows Bridge. The wind gusted at the resonant frequency of the bridge structure.

To picture positive feedback, watch this video of a guitar lesson on how to make that sound at the beginning of Foxy Lady by Jimi Hendrix (you have to hold the guitar up to the amplifier in just the right way).

The central bank may be able to push down the rate of interest, at least initially. However, they have no control over the time preference of savers. Normally interest is above time preference. But if they push interest below, then the violated savers will take action. Suffice to say that in this state, they prefer to hoard commodities rather than buy the bond offering interest that’s too low (read Keith’s theory of interest and prices for the full detail). If gold is legally permissible to be hoarded, then it’s the best good for hoarding.

The last time interest was below time preference was in the 1970’s. And boy did the gold price rise during that decade. Not because the interest rate was rising per se, but because interest was below time preference. Alas, as interest rose, so did time preference. Like a ratchet.

We are looking at a spread—interest to time preference—and it cannot be measured directly, as there is no economic data series for marginal time preference or the marginal saver.

Notwithstanding the Fed’s recent toying with higher rates, we are still in the same falling trend ongoing since 1981. Each downtick in the interest rate may push it below some dollar holder’s time preference. These marginal dollar holders may buy gold.

Our Call

Gold closed the year 2020 around $1,900 (the Monetary Metals calculated gold fundamental price was a few hundred below that, but as we said earlier, we believe this is an artifact of the disruption due to Covid lockdowns and increasing regulatory pressure on bullion banks, and not an accurate fundamental price).

Silver closed the year around $26.50 (our calculated fundamental price was $23.72).

Every year, we note that fundamentals can and do change. And longer-term predictions demand more than just looking at the basis. We are trying to imagine what will happen after the Reddit threads about silver, after the rumors that buying silver will harm the banks subside (again), and after the momentum of the moment inevitably dwindles.

Last year, we wrote:

“From the crisis through 2011, the prices of the metals ran up due to the inflation trade: “Oh my God, they are printing money to infinity! Buy gold and silver before they go to the moon!”

Then, that trend ended. While the money supply certainly did not collapse, supply and demand fundamentals caused lower prices in one commodity after another. Copper, for example, peaked in early 2011. Oil had an epic collapse. Wheat dropped through the end of 2016, though it’s bounced a bit since then.

The next several years were a period of despair alternating with hope as the prices of the metals fell and fell, and then rallied. It took from August 2011 when the price of gold hits its peak just under $2,000 until December 2015, when the price hit its trough a bit over half that level.

Since then, we think most chartists would agree that the gold price is in an uptrend. But the question is: where to, from here?

The central banks have been fighting mightily to keep the current boom going. It has been going so long now, that it has to be a record length without a bust. We have been saying for many years that this requires the interest rate continue to drop. The Fed briefly tried to disagree, but has now been forced to concede. We believe that they are now in the position, known in the game of chess, as zugzwang, at least regarding the gold price.

If they continue to succeed for a while longer, they are pushing the interest down even further. As it falls below the time preference of more and more savers, more and more of them will turn to gold in preference to dollars (let alone Swiss francs or euros with negative yields). This will drive up the price.

If they fail, then risk (or the perception of risk) will begin skyrocketing. People will turn to gold as the financial asset without counterparty risk. This will drive up the price.

We believe it is likely that gold will trade over $1,650 during 2020. We would not bet against it trading higher, perhaps much higher.”

Nothing fundamental (pun intended) has changed since last year. Covid has accelerated the then-existing fiscal trend (bigger and bigger deficit spending, weaker and weaker job market especially for unskilled labor and skilled trades, not necessarily for IT security consultants or digital signal processing software experts). And the then-existing monetary trend of falling interest rates.

At the start of 2019, the 10-year Treasury paid a yield of 2.7%. At the start of last year, this rate was down to 1.9%. In the wake of Covid, it plunged to 0.5%. Now it appears to be in an “uptrend”, currently around 1.1% (a level far below any historical precedent prior to Covid).

The risk of being a creditor to the government has dramatically increased. The baseline deficit was $1.7 trillion. This is the increase in debt from April 1, 2019 to March 31, 2020, just prior to the spending unleashed by the so-called CARES Act (the official deficit number is lower than this, due to an accounting gimmick). Then CARES and its supplement added another $2.8 trillion of spending. Biden is now adding $1.9 trillion. So $4.7 trillion of spending is added to a baseline of $1.7 trillion, for a total deficit in a 12-month period of $6.4 trillion. And this does not count the drop in tax revenues, which we estimate to be many hundreds of billions (not to mention cumulative over the coming years).

At the same time, the return has dropped precipitously. Who seriously thinks that it is a good deal to lend for ten years and get 1.1% return on dollars? We remind everyone that the Fed promises to debase the dollar at 2% per annum.

It feels to us, and this is based on observation, conversations with clients and industry professionals (especially those who have not been perma-bulls), that we are in a different era for the gold market than the bear market period 2012-2018. Or the bull market period 2002-2008. There are monetary system problems and pressures which are much more serious—and much more obviously serious—than the halcyon days when President Bush told everyone to buy a house and go shopping.

And compared even to the manic period of 2009-2011, the reasons for buying gold are not so often cited as inflation per se. Many felt that the unprecedented policy responses in 2009 were justified due to the crisis. Today that justification has faded and people are more cynical about a “crisis” that appears to still be ongoing 12 years later. And skeptical that there is any way out.

The biggest difference is that, at the moment, there seems to be little awareness that gold is in a bull market. There have been a few mentions of a silver “short squeeze”, but otherwise this is akin to the “stealth bull market” of 2002 through 2006. It happened, but “nobody” knew about it.

It has the feel of something that could be sustainable for a long period of time. Unlike, say, frantic panic-buying to protect against an “inflation” that never seemed to come as in 2009-2011.

We predict that the price of gold will test $2,000 again this year, perhaps not dropping below ever again. And what’s the opportunity cost to buy gold? A risk of a temporary price drop? Compared to what within the dollar? All but zero interest (and zero or negative in other currencies), ongoing debasement, and the mother of all credit crises inevitable (if not imminent). It seems a no-brainer, not just to Monetary Metals’ readers, but we think to a growing number of people.

Whither gold’s little brother, silver?

Silver is more the plaything of retail (also the best physical metal to buy, if one is buying 10% of one’s weekly wage). However, institutions have been noticing that it is relatively undervalued compared to gold.

And we note that the gold-silver ratio showed a bear market for silver since 2011. That is, the price of silver, measured in gold, had been falling. It eventually hit a low of 1/125th ounce of gold in March just when Covid lockdowns began. Since then, it’s been falling (i.e. the price of silver has been rising). The ratio is now well under 70.

This trend is still young, about 3 quarters. We see little reason for it to end now. That is, we expect the gold-silver ratio to keep falling. So along with gold over $2,000, we would not be at all surprised at a gold-silver ratio under 60 by year’s end. $2000 gold divided by ratio of 60 would give us a silver price over $33.

To anyone who does not yet own gold or silver, we offer the same advice as always. You should own some, period. Without regard to price.

We will continue to chronicle the changing dynamics in the Monetary Metals Supply and Demand Report every week. Subscribers will be the first to see any shift when it occurs. And, of course, if we see signs of a credit crisis, we will write about it.

It is important to note one caveat. As with equities, fundamental analysis does not help you time the market. Timing is not what we are trying to do. We are doing something that has become unfashionable.

We are interested in valuing the market.

Thank you.

Your frequent lighthouse-and-boat analogy comes to mind as I think of Monetary Metals as a steady lighthouse across seven years of reading.

Jasno, przejrzyście i na temat. Dziękuję i pozdrawiam serdecznie.

I have one more thing for you to price relative to gold.

The education you just gave us in this article. Priceless.

Keith – an example of capital destruction that comes to mind is what can happen to a nice clean well-run laundromat. I’ve seen it happen twice, once slowly and once rapidly. I used to call it ‘asset-stripping’, but after reading here will call it ‘capital destruction’. It’s not just the lack of maintenance on the machines, allowing them to fail one-by-one, and accumulate dirt and grime. It’s the broken money-machine, the floors, the glass, the counter-help, and over time, the clientele itself. It’s a process that you can adapt to like our 30-year fling with outsourcing and off-shoring, but there comes a point where as a customer you’ve ‘had it’. The ‘magic’ of turning capital that someone patiently grew into mere dollars is a bane on society at large. The laundromat example is the polite version of a mafia bust-out, usually of a restaurant or club, where after loading-up an enterprise with debt and quietly selling-off the equipment, they burn it down for the insurance too, before declaring bankruptcy.

Bring me in!

I am a convert after reading this report.

I first saw Keith Weiner on a Delingpod early this week and he seemed to have an answer to my stress of having too many US$ held in accounts. I have been aware that I needed to divest quickly, but to what?

Now I know…Thanks for the lifebelt Keith. I’m in!