When it comes to analyzing precious metals, the right methodology isn’t immediately obvious. Fundamental analysis in stocks and bonds is well understood. One can discount cash flows, examine the balance sheet, review the income statement, look at growth prospects and arrive at a fundamental value for the company. And there is a sophisticated ratings system for the debt of those same companies.

Commodities are different. Oil doesn’t have a balance sheet. Sugar doesn’t have an income statement. Gold doesn’t have cash flows (though it does generate a yield thanks to our Gold Fixed Income program). Not to mention that while sugar, oil, and gold may be part of the same class (commodities), it would be a grave mistake to consider them the same species. Cheese and chalk are not the same, despite both words starting with the same phonetic “ch.”

Conventional analysis for commodities hinges on understanding supply and demand dynamics for each commodity. This would involve looking at both the supply side and the demand side and answering questions like; Are there shortages or surpluses? Is demand growing or shrinking? From which markets? And what are the drivers of those increases or decreases?

We would never say this analysis is easy, but it is simple, as in, an 8th grader can understand it. But does this same kind of conventional analysis apply to gold and silver?

No.

It is precisely because gold is not just another commodity that it defies this kind of conventional analysis.

Gold, Not Just Another Commodity

It’s important not to gloss over this point. Thanks to the rise of bitcoin, and the increasingly obvious failure of the dollar, questions about the nature of money are more popular and relevant than ever before. So, what are the reasons why gold and silver are monetary metals, and not just mere commodities?

To begin, gold is not consumed in the same way that oil, sugar, and wheat are. As the famous refrain goes, “You can’t eat gold!” Well, actually you can but the broader point is, “Why would you want to?!”

It’s not consumed because it’s too valuable. We would rather hold onto it, in some form, than dispose of it. That’s not true of oil, sugar or wheat. Not to mention how difficult it would be to “hold onto” those things. In the case of oil, by difficult we mean toxic, hazardous, and costly. You would need some serious square footage and heavy equipment to store any meaningful amount of oil. Whereas you can hold 500 – 1,000 oz ($1-$2Million) of gold in your backpack.

Second, even if we wanted to “consume it” we couldn’t. Pure gold is virtually indestructible. Unless you’re within walking distance of Mount Doom in Mordor, good luck trying to destroy your gold!

These two reasons lead us to a startling conclusion–all of the gold ever mined in human history is still here.

The implications of this are extraordinary.

And the least of them is that you may be wearing the same gold as Cleopatra. Or that the gold interest you earn with Monetary Metals may be the same gold the De Medici family used to finance the Renaissance.

And, the implications go far beyond mere curiosities.

Understanding Gold Supply

The first implication is that the number that represents the total “supply” of gold is a very, very large number. The World Gold Council estimates this to be about 201,296 tons. That’s over 6 billion ounces, and just shy of $12 trillion dollars (as of this writing).

We think this number underestimates it, potentially by multiples. Why? For two reasons. Humans have been accumulating gold for a very, very long time.

The oldest known gold coin has been dated to the 7th century B.C. by historians. But that’s the earliest evidence we have of gold coin. To find the earliest record of humans valuing and accumulating gold itself, we go an additional several thousand years further back in history for that.

Second, gold isn’t exactly the kind of thing people mention that they have. That’s as true today as it ever was.

The fact is that every ounce of gold that humans have ever accumulated could be potential supply. On short notice, it’s just a quick trip to a refiner to turn jewelry or objets d’art into bullion.

This fact should turn any attempt at conventional analysis for gold upside down. It means there’s no such thing as a glut in gold. There’s no such thing as oversupply. People are happy to keep stacking gold today, and for all the today’s going back thousands of years.

It means annual mine production numbers are virtually meaningless (though not to the miners). Using the official estimate, annual mine production accounts for about a 1.7% increase in the total supply of gold. In other words, it’s the proverbial drop in the bucket. There can be more gold volume traded in a day, than what is produced annually.

The technical term for this is Stocks to Flows. In regular commodities, this same ratio—stocks to flows—is measured in months. We just don’t hoard wheat and oil for the long term, for obvious reasons. Nor even iron or lumber or other durable materials. But for gold, and to a lesser extent silver, the stocks to flow ratio is measured in decades of annual production, not months. Increases in gold production does not pose a threat to collapsing the price the way that increases in oil production might.

Understanding Gold Demand

So, we’ve covered the supply side. What about demand?

What would lead humans to demand gold and silver this way, for all those years?

There is only one conceivable answer. It’s because these metals are money.

Consider the marginal utility of gold compared to other commodities. People are happy to accept the 1,001st ounce of gold, on the same terms as the 1,000th or the 1st ounce. It doesn’t hurt that you could carry those 1,000 ounces in a backpack, nor that you can find a ready market for it anywhere in the world, from London to Lisbon to Lagos to LA to Lima to Laos. The same cannot be said for any other commodity, with the exception of silver.

the marginal utility of gold compared to other commodities. People are happy to accept the 1,001st ounce of gold, on the same terms as the 1,000th or the 1st ounce. It doesn’t hurt that you could carry those 1,000 ounces in a backpack, nor that you can find a ready market for it anywhere in the world, from London to Lisbon to Lagos to LA to Lima to Laos. The same cannot be said for any other commodity, with the exception of silver.

This too has profound implications. One, if gold and silver are money, then what is the dollar? We’ve asked and answered that question many, many times and we won’t rehash here.

We want to discuss the implications of gold and silver’s moneyness on attempts to analyze their “price.” We put “price” in quotations because it’s really gold that should be the lens through which we talk about the price of the dollar, not the opposite.

To recap, here’s where we are:

Supply: All the above-ground gold that humans have been accumulating for millennia, under the right conditions and at the right price.

Demand: Virtually everyone on the planet under the right conditions and at the right price.

This leads to the following.

A change in the desire to hoard or dishoard gold, even a small one, can have a big impact on price.

So, how does one go about measuring the desire to hoard or dishoard gold?

The answer to this question forms the basis (pun intended, if you know, you know) of our Supply and Demand model for gold and silver.

The Only Way to Do Fundamental Analysis of Gold and Silver

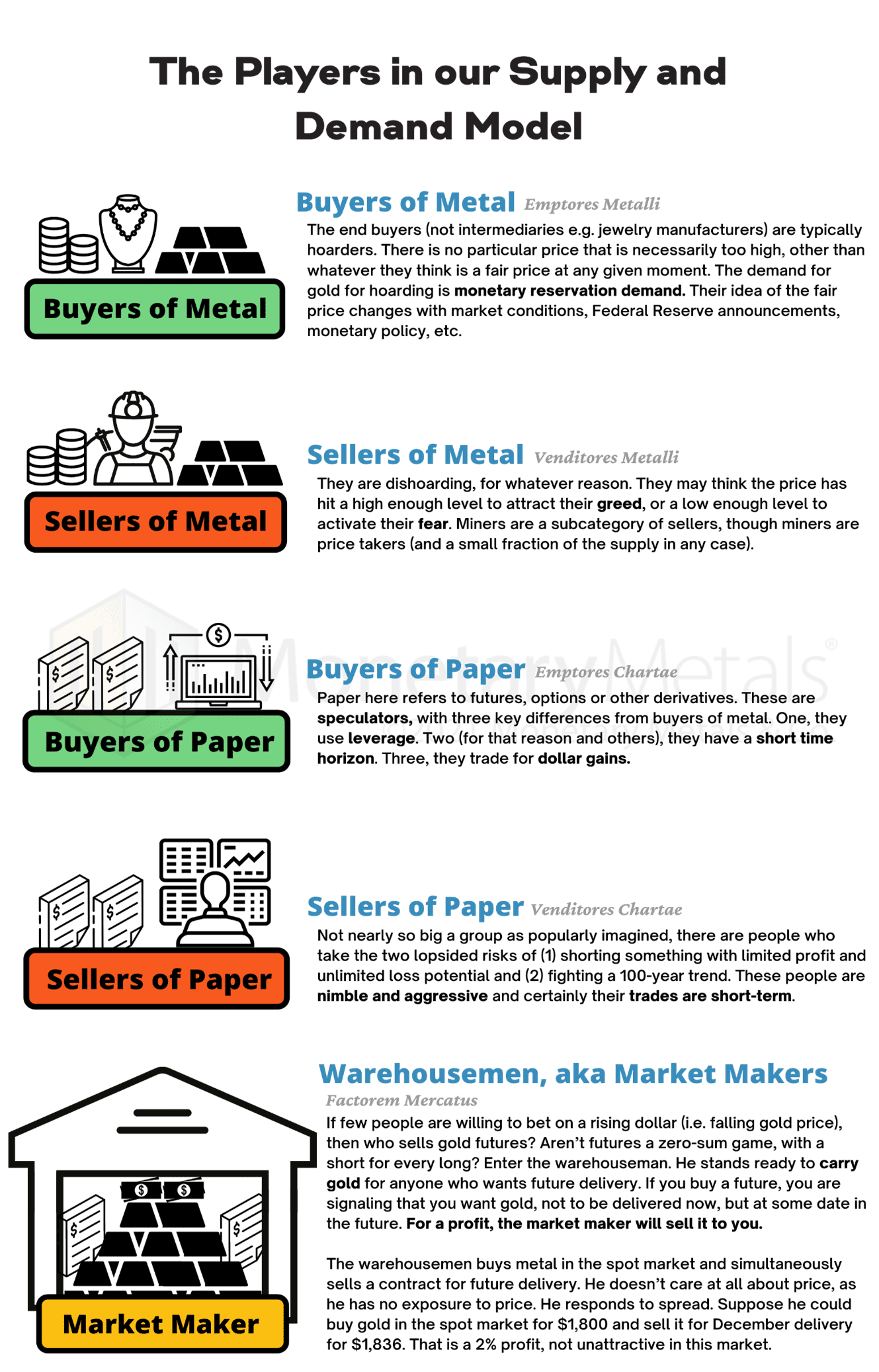

To understand our Supply and Demand model, you must first understand the players. We divide the market into five different actors. Here’s a graphic to orient you to our framework.

It’s important to keep in mind that virtually all of the gold ever mined is in someone’s hoard. However, the market can experience seasons of relative abundance and scarcity. The spreads of the warehouseman provide a good signal to see it.

If there is a big spread between spot and futures—called the basis—then this means two things. One, speculators (typically buyers of paper) are bidding up futures contracts. And two, the marginal use of gold is to go into the warehouse. This is a signal that gold is relatively abundant in the market.

Normally, the price in the futures market is higher than the price in the spot market. This is called contango. Contango means it is profitable to carry the metal, which is to buy a metal bar and sell a future against it. However, the basis spread can invert—and it has many times since the crisis of 2008. When it is inverted—called backwardation—which means it’s profitable to sell metal and buy a future. Such decarrying is, by conventional standards, risk free (it’s not, see below). It should never happen in gold, as it is a sign of shortage and there is no such thing as a shortage in a metal which has been hoarded for millennia. Backwardation, therefore, is a signal of relative scarcity of gold in the market. It’s a signal to the warehouseman to empty out the warehouse.

In backwardation, the marginal supply of metal is coming from the warehouse (carry trades are unwinding). Obviously, there is only a finite supply of gold held in carry. Thus, backwardation typically heralds a rising price.

To recap, by analyzing the spreads of the market makers in precious metals, we get a glimpse of the activity of all five market participants. A rising basis (growing profitability to carry gold) signals relative abundance. A falling basis/rising cobasis (growing profitability to de-carry gold) signals relative scarcity. Generally, rising abundance warns of a price decline, while rising scarcity presages a price increase.

This is the only way to analyze supply and demand fundamentals for the monetary metals. The five market participants interact to form a constantly changing dynamic. It is this dynamic that we study when we look at spreads between spot and futures, and changes to these spreads.

Supply and Demand Report

Monetary Metals has developed a proprietary model based on this theory, which outputs the Fundamental Price for each metal. This is updated every day on our website. We provide many charts and analyses of our indicators. We also have a newsletter, The Supply and Demand Report, where we chronicle changes in the fundamentals for gold and silver. You can subscribe to that report by clicking the “Subscribe” button in the right side of this post.

The supply and demand fundamentals are a great signal for where prices are likely headed in the short term, but they are not suited for longer term predictions. That is because the model tells us what the participants are doing, not why they’re doing it. To understand the why, we must incorporate broader macroeconomic analysis like inflation, interest rates, the madness of Central Bankers, and even wildcards like Bitcoin. You can read more about our macroeconomic outlook and other views that affect gold and silver on our Economics and Gold Research page. It’s our tradition every year to survey the macroeconomic landscape and publish where we think gold and silver prices are going in our annual Gold Outlook Reports.

Make sure to subscribe to our YouTube Channel to check out all our Media Appearances, Podcast Episodes and more!

Additional Resources for Earning Interest on Gold

If you’d like to learn more about how to earn interest on gold with Monetary Metals, check out the following resources:

In this paper we look at how conventional gold holdings stack up to Monetary Metals Investments, which offer a Yield on Gold, Paid in Gold®. We compare retail coins, vault storage, the popular ETF – GLD, and mining stocks against Monetary Metals’ True Gold Leases.

The Case for Gold Yield in Investment Portfolios

Adding gold to a diversified portfolio of assets reduces volatility and increases returns. But how much and what about the ongoing costs? What changes when gold pays a yield? This paper answers those questions using data going back to 1972.

:

: