The United States, and every country, is subject to a monetary authority and legal tender laws. Here in the U.S. we have the Federal Reserve, a central bank that plans money and credit. The Fed thought they had perfected their planning (but of course it cannot be perfected). They thought they had ended the boom and bust cycle, and brought us into a brave new era, their so-called great moderation that ended in 2008. All they really did was manage the banking system to the brink of insolvency.

Let’s try a thought experiment. Suppose the monetary central planner attempts to fix the problem of insolvency by massive injections of liquidity. The central bank buys bonds. It dictates rates near zero on the short end of the yield curve, and promises not to raise rates for years to come. What perverse outcome would we expect?

Arbitrageurs see a green light, telling them that they can safely borrow short to buy long bonds. As the price of a bond goes up, the rate of interest goes down—it’s a rigid mathematical inverse. This is how suppression of short-term rates causes suppression of long-term rates.

This poses a problem for investors. Every investor has a minimum yield he must earn in order to meet his goals, such as retirement. When the yield available in government bonds falls, this gives the investor a strong push to other bonds with higher yields. Some Treasury bond owners sell, and go into AAA corporate bonds. This, of course, pushes up bond prices and pushes down the yield. This pushes some AAA corporate investors into AA bonds. And so on.

The net yield earned by every investor is pushed lower. However, at each step in the process, the effect is diminished. The wave of credit does not quite make it all the way to the other side of the pool, where the small businesses are trying to get wet.

In a free or semi-free market, credit is generally plentiful and inexpensive for mature, large enterprises. When well managed, these companies offer a low credit risk. Conversely, it has always been difficult for startups to obtain credit. When they can get it, they have to pay dearly. In other words, there is a credit gradient.

A gradient describes a change in concentration of something as you move through a range of coordinates. For example, this is a color gradient.

Of course, there is always a credit gradient. Only now, the Federal Reserve has exaggerated it to an extreme. They have made the gradient steeper.

The biggest players are drunk, chugging as much as they want. At the same time, the scrappy disruptors with the greatest opportunities to improve our world are more dehydrated than ever. Worse yet, the innovators have to try to compete for resources with the large corporations.

The credit gradient is artificially enhanced. The end result is not surprising.

I came across this paper, by the Brookings Institute. Authors Ian Hathaway and Robert Litan found that “Like the population, the business sector of the U.S. economy is aging. … The share of firms aged 16 years or more was 23 percent in 1992, but leaped to 34 percent by 2011—an increase of 50 percent in two decades.”

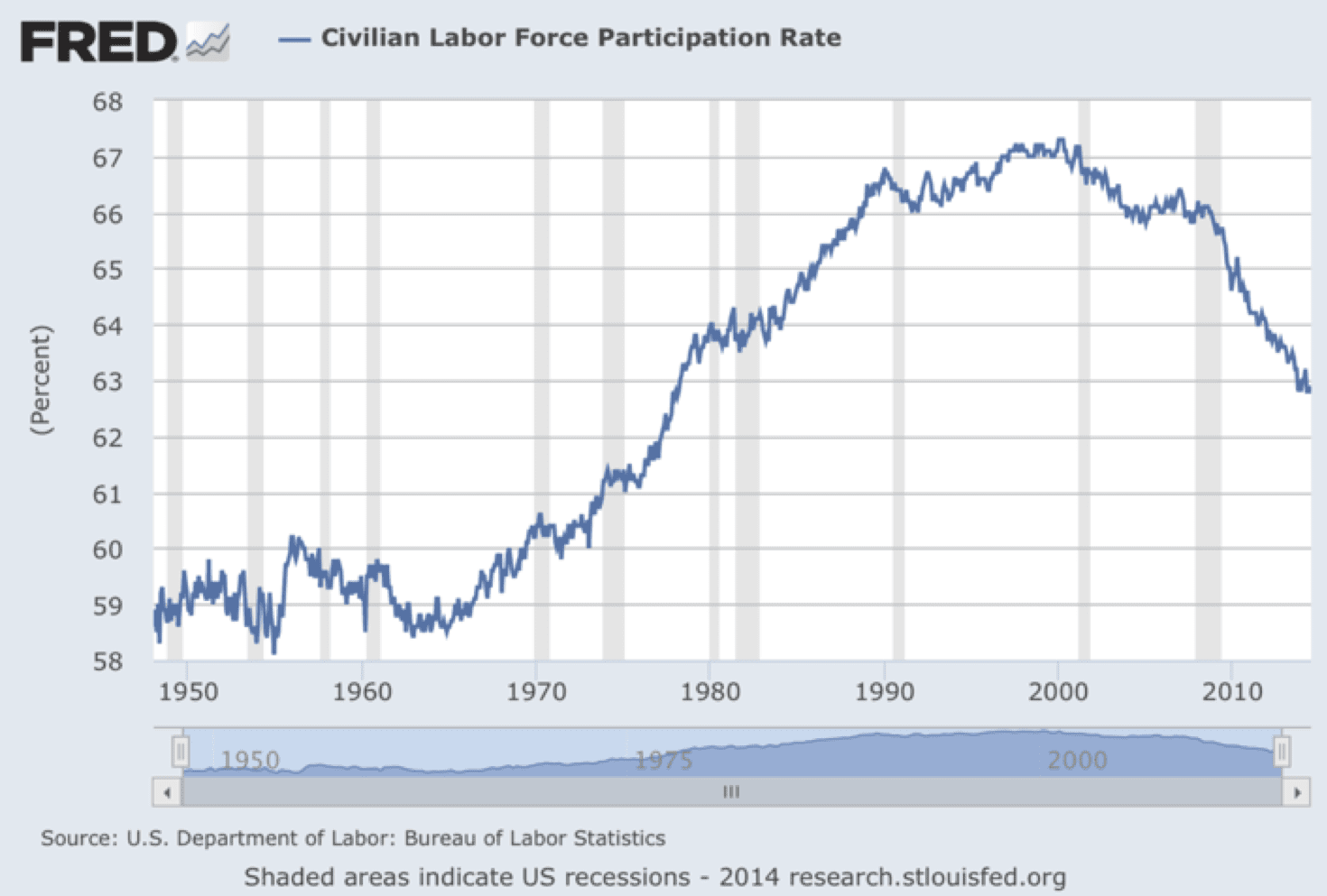

Entrepreneurial young companies are not hiring, or in many cases, surviving. The older, larger ones are all that remain. Their hiring is anemic compared to that of younger companies. The proof is in the labor force participation rate, which shows the percentage of working age people who are employed or seeking employment. It is now down to a level last seen during the Carter Administration in the late 1970’s.

Although there are other factors that contribute to this dismal reality including minimum wage and labor law, taxes, environmentalism, subsidies for crony companies, and regulations, the artificially enhanced credit gradient deserves the lion’s share of the blame.

:

:

Perfect explanation.

Keith, agree with the view. However, where one funding source vacates another one takes its place. There are more angel investors / venture capitalists now because they are willing to take on higher risk in exchange for higher reward.

The side effect to a ultra low interest rate environment which I observed, and personal opinion is the speed of change / innovation cycle have sped up. In the past new innovations will enjoy a good number of years recouping ther cost plus reaping the profits but nowadays they have a much shorter cycle and have to constantly stay on the edge.

There’s a equilibrium and yet almost a vicious cycle that spirals downwards. I wonder when it will ever stop.

Yuhanni: I think the angels and VCs have been in a process of moving away from risk, which began after 2001. Today there are more angels I am sure, but they’re pretty picky about deals. To the point of this article, angles are not typically interested in financing a restaurant, factory, car dealership, or the like.

And of course angel capital is extremely expensive to the entrepreneur. While the large corporation is gorging on credit it can have for the low cost of 100 basis points or so, an entrepreneur has to give up a third or more of the equity in his company. The large corporation can use the proceeds to enrich management by buying back shares, driving the price up, and triggering executive bonuses tied to stock performance. The entrepreneur may not be able to use the proceeds even to pay himself a salary.

Yuhanni, in my industry, venture capital has been scarce for the past 10 years. There are a couple of factors involved. First, my industry (Electronic Design Automation) is relatively mature in the high tech sector. However, more importantly, VCs want to put their money into social media startups due to the perceived payback. If a VC invested $10M in an EDA startup, they’d be extremely lucky to get 3-5x on their money in 10 years. That much money in a social media startup could return 10-100x in less than 10 years. (Historically. I think that era is just about over.) This is surely due more to the mania in social media stocks than anything else. However, money goes where the promise for return is biggest.

Meanwhile, we are left to contemplate why millions and billions are going into social media which has a spotty record of actual productivity gains and seems to gain most of its value by obsoleting old-style advertising (shifting revenue from an established bucket to another bucket, not growing the bucket). The productivity gains are real, but very hard to measure. For those old enough, how much more do you get done today given that 50% of your work day or more (certainly true for many people in my industry) is consumed with email reading and responding? Yeah, all that information is worth something, but half a person’s day in productivity every day? On the other hand, my industry is critical to enabling the semiconductor industry, which generates >$100B/year. Without EDA, there could not have been Moore’s Law (2x increase in function and speed every 18-24 months) in computers, enabling smartphones, tablets, the internet, etc. That is real and relatively easily measurable productivity. Yet, VCs don’t want to touch startups in EDA.

I’ll give one example. It is my job to analyze and direct my division into new technology areas. As a result, I talk to startups and evaluate whether they have anything worth acquiring. One that I talked to recently is working in an area of interest. We already did one acquisition that puts us into that same market. However, this startup has ~$10M in VC funding. In order for a large EDA company to acquire a startup for an amount that pays back the investors (0 return), the startup must achieve on the order of $30-50M in annual revenue. That would take years to achieve even with a standout product and good marketing/sales. I cannot comment on whether they have a standout product. The finances are such that it isn’t worth our time to do the due diligence. I expect this company to fail. It makes no sense for the investors to put more money into this startup. They’ll try to sell it off. Without adequate revenue and no funds to build a sales force to generate it, the VCs are looking at getting <$0.50 of every $1 they put into this startup.

Sure, there are situations where the investors could've gotten back their investment and maybe a bit of a return. But, this example shows that something's broken in this industry. It isn't particular to this one startup company. The VC risk-reward analysis is upside down.

Another example is a networking startup that has ~$160M invested. Will this company generate a return for its investors? In this case, it is possible. They appear on the verge of reinventing how network chips are designed and implemented. But, this is a different industry from EDA. It is networking. VC funds are still flowing to semiconductor companies (the customers of EDA), but not as much as social media and the heyday of the 1990's.

Keith – I’ve been enjoying your newsletters for some time now and I really respect your insight and opinions. I do wonder about a few things in this particular commentary. I’m not sure I understand why newer businesses are “dehydrated.” It seems they’d have little trouble issuing debt since people are buying lower and lower rated bonds to get the higher interest. I also wonder if the aging population would account for a good share of the decrease in the labor force participation rate due to retirement or the choice to reduce hours?? Thank you for all your wonderful commentaries.

Update: I see the participation rate refers to working age.

bvigorda: The typical startup does not have access to the bond market. At best, it can borrow from a bank, and the bank might be able to securitize the loan and sell off a pool of such loans into the bond market (if the regulators allow it).

Thanks Keith!

Very few can write the way you do Keith. Thank you , your explanations are always very concise and genius !