How Not to Predict Interest Rates

We continue our hiatus from capital destruction to look further at interest rates. Last week, our Report was almost prescient. We said:

The first thing we must say about this is that people should pick one: (A) rising stock market or (B) rising interest rates. They both cannot be true (though we could have falling rates and falling stocks).

We write these Reports over the weekend. At the time of last week’s writing session, Friday’s close on the S&P was 2757 (futures). Monday this week saw a crash, with the S&P down to 2529 at the low point in the evening. That is a drop of -8.3%.

We are not stock prognosticators, and we will neither tell you “short the market” nor “buy the dip”. We have a different point to make.

Rising interest rates, by a variety of mechanisms, cause stocks and all asset prices to go down. We have touched on a few in this Report. One is that investors have a choice between the risk-free asset—the Treasury bond—and anything else (note: the Treasury bond is not risk free, but if it defaults then everything else will be wiped out in the collapse). Why would they accept a lower yield on stocks along with the greater risk? Another is that corporations can borrow to buy their own shares. Management may do this if the interest rate is lower than their shares yield. But they can sell shares to pay off debt if the shares have lower yield than the interest rate.

Let’s look at a few more.

Consider home buyers. It is well understood that most people are monthly payment borrowers. That is, they have a budget for the mortgage payment and fit the house to that budget. If the typical middle class family can afford $2,500 a month, that’s it. When the 30-year fixed mortgage rate was 3.4% in 2013, this family could afford to finance $565,000. Today, at 4%, the amount is down to $525,000.

Interestingly, the 30-year mortgage rate illustrates our ongoing theme. Demand for credit is soft. In a time when 12-month LIBOR was under 0.8%, the 30-year mortgage rate was 3.4%. Now that LIBOR has risen to 2.3%, a gain of 1.5%, the 30-year mortgage is going for 4%, or only 0.6% higher. If the mortgage had increased by the same 1.5%, it would be 4.9% and this family would be down to financing $472,000.

And it gets worse. In a falling rates environment, many people take Adjustable Rate Mortgages (ARMs) with a balloon payment at the end, which is another form of duration mismatch. So the relevant 2013 comparison is not 3.4% but 2.6%. At 2.6%, someone willing to use an ARM—we will call him the marginal home buyer—could finance $625,000.

In rising rates environment, we assume that most people will want to fix their mortgage rate. And now there is a consensus, from Fed propagandists to the gold bugs and everyone in between. Everyone thinks that rates are rising. So the relevant comparison for amount financed between 2013 and today is $625,000 to $472,000, a drop of -24%.

Let’s move on to the automakers. At least in the US (we don’t know if this occurs in other countries), they are advertising 0% to finance a new car for 72 months. Of course, the carmakers cannot borrow for free. Let’s assume they are playing the duration mismatch game, and using 1-year maturities, because it’s a lower rate. The disadvantage of financing a 6-year loan with a 1-year liability is that you must roll the liability five times, on each anniversary. The advantage is that the rate is lower.

In any case, their cost of borrowing has increased substantially. In late 2014, 1-year LIBOR was 0.56%. It has risen relentlessly since the end of 2014. Today, it is 2.31%, a gain of +1.8%. This adds $18 million a year of cost, for every billion financed.

Ford sales for the last 12 months are over $150 billion. Even if a quarter of their sales were financed this way, the increase in cost of borrowing over the last three years is $690 million. That covers a year’s worth of sales. But since the company has to carry this debt for up to 6 years, assume annual increase in interest expense is double that (it would be complicated to calculate and we would need more information, but double seems conservative), or $1.38 billion.

Rising interest has added costs which are a big in relation to the automakers’ annual profits, Ford makes around $5 billion a year.

This situation—rising rates to the car companies, but zero interest to consumers—helps proves our case that we are in a falling-rates regime. A falling rates dynamic has soft demand for credit, which increases only when the interest rate ticks down.

The car companies rightly fear what would happen to sales volume if they tried to pass through even just the increase in the cost of borrowing. If they offered 1.8% financing, they would sell fewer cars. Many fewer.

If the rate ticked down enough for them to offer financing at -1%, then that would really boost sales!

This same thing is playing out in all consumer durables, from four-wheelers, to furniture, to boats, to kitchen cabinets.

And likely in commercial real estate. When a landlord finds a creditworthy tenant who is willing to sign a 5-year lease, the landlord may spend some money building out the space to the tenant’s needs. The cost of this has to be amortized in the rent. How much should the landlord be willing to spend, and how does the landlord calculate amortization? A higher interest rate means it’s harder to subsidize the cost of accommodating the tenant’s needs. But if there is a high vacancy rate, the landlord may be caught between a rock and a hard place. Either don’t do it, leave the space empty, and default on the mortgage. Or do it, add to the monthly debt service burden, and risk default—in hopes of increasing the chance of finding other tenants for the other empty spaces in the building.

The rising cost of borrowing is squeezing landlords, making them less willing (and able) to borrow more for new projects.

Now let’s get back to that most people expect rates to rise. Last week, we discussed the causes and effects of the rising cycle (which last occurred 1947-1981) and the present falling cycle since 1981. We said it would take either a miracle or a calamity to reverse and cause a rising cycle. A miracle would be rising productivity and rising profits. A calamity would be rising time preference. And rising rates would cause a calamity—a cascading series of defaults.

However, the idea of rising rates persists. One idea we have seen discussed this week is the effect of rising debt. Massive growth in the national debt is likely coming to America, thanks to a deal between the party of spend more and the party of tax less. This will likely cause an increase in money supply. Because of this, it is argued, interest rates must rise.

Let’s look at that. Here is a graph of the M2 money supply and US government debt along with the interest rate on the 10-year Treasury (all data courtesy of the St Louis Fed).

For this time period, we see that M2 and debt are highly correlated, and anti-correlated with interest. We have indexed debt and M2 as we are only trying to show the correlation.

We went back only to 1981, not because it’s the start of the current falling rates cycle, but because the data does not go back farther. If we had looked 1947 to 1981, we would see debt going from $258 billion to $998 billion, an increase of 287%. At the same time, M2 went from $146 billion to $1.8 trillion (courtesy econdataus.com), or 1,133%. Due to a change in sources in this data set, the change could be overstated by perhaps 400%.

The point remains, the rising cycle and the falling cycle both have rising government debt and rising quantity of dollars. That’s just how a centrally banked fiat currency works. It’s a feature, not a bug. But it does not always have rising rates. It can have—and does right now—falling rates.

Therefore, we emphasize our conclusion. You cannot say that rising debt or rising quantity of dollars will cause rising interest rates. Rising debt/M2 has not correlated with interest rates for 37 years.

If you think that as of 2018 a new correlation will begin, we encourage you to describe your theory. And please write to us. We would love to look at a new theory.

The above ideas are an application of Keith’s Theory of Interest and Prices in Paper Currency.

Geocentric vs Heliocentric

Before Copernicus, people believed that the sun and planets revolved around the Earth. But it was pretty complicated to explain the retrograde motion of the planets. And it led to a question. What would cause an object to slow down and reverse? Nothing on Earth behaves like this.

The heliocentric model of Copernicus is much simpler. Each planet goes around the sun in a circle (later they realized the orbits are actually not circles but ellipses).

Today, we have a dollarcentric view analogous to the geocentric view of the Medievals. Analogous to retrograde motion of planets, is the question of whether gold or stocks are outperforming. According to the dollarcentric view, the S&P stock index fell from 2,757 to 2,619, or -5% this week. And gold fell from $1,333 to $1,316, or -1.28%. So most people say stocks underperformed. And most gold bugs are excited, because this (supposedly) supports a case that gold is going back into a bull market. For reference, silver fell from $16.56 to $16.32, or -1.45%. So silver underperformed gold. Which would not be supportive of the gold bull market thesis.

When the markets realize that the dollarcentric view is wrong, we will have a revolution in monetary science, just as Copernicus ushered in a revolution in physical science.

We should be saying that the dollar went up, from 23.3mg gold to 23.6mg. And stocks fell from 2.07oz to 1.99oz gold.

This should not be a radical idea. Even dollar advocates admit that the dollar goes down—indeed the stated goal of the Fed is 2% decline per annum. And they also admit that there can be long leads and lags, years or decades. So this unit, which is an ever-stretching rubber band subject to unpredictable volatility is supposed to be the unit of measure.

And gold, which is not subject to central planning, is just one alternative of many investments—all to be measured in centrally planned rubber bands.

You cannot understand the solar system, if you are trying to measure the backward motion of Venus against the forward travel of Mars, using the Earth as the center. And you cannot understand the markets if you try to measure the upward motion of gold against the downward motion of stocks, using the dollar as the center.

Gold standard aside, this revolution is necessary, and we believe that it’s coming. It will have to, as our currency becomes more volatile. Those stuck believing that our gyrating, failing currency is the center, while it goes off the rails, will not be able to grasp what happens.

Supply and Demand Fundamentals

Let’s take a look at the only true picture of the supply and demand fundamentals for the metals. But first, here is the chart of the prices of gold and silver.

Next, this is a graph of the gold price measured in silver, otherwise known as the gold to silver ratio (see here for an explanation of bid and offer prices for the ratio). The ratio rose.

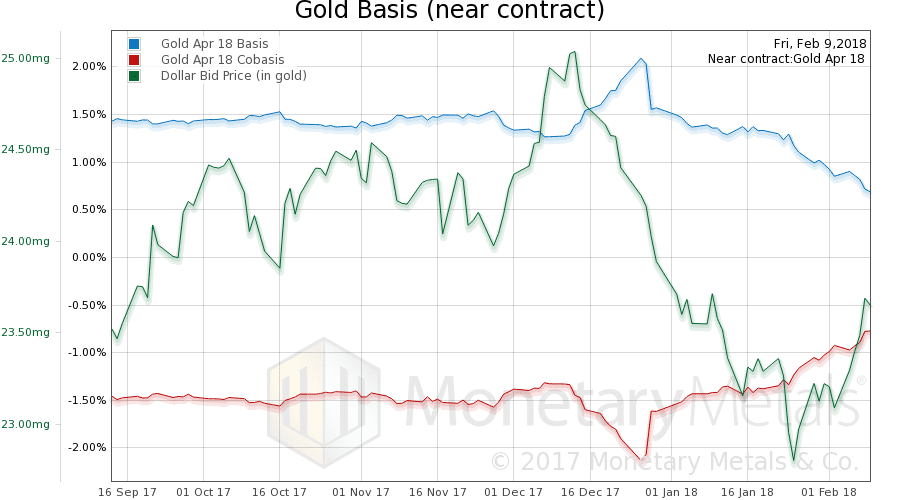

Here is the gold graph showing gold basis, cobasis and the price of the dollar in terms of gold price.

The uptrend of the cobasis (scarcity) continued this week. Not surprising with falling price. The Monetary Metals Gold Fundamental Price rose $14 this week, to $1,386. Now let’s look at silver.

The same thing is happening in silver (though beware the effect of the control roll, this is the March contract which hits First Notice day in a few short weeks). The Monetary Metals Silver Fundamental Price fell 30 cents to $16.93.

We promised to write an article about the silver price and basis action of Friday last week (Feb 2). We did not do that, so please see the chart below.

What we look for when analyzing intra-day price moves is the behavior of the price in relation to the basis. Friday’s action is similar to many of our previous intra-day Forensic Analysis, where we see that price and basis move together, in this case both falling.

This is a picture of selling primarily in the futures markets, or to put it another way, that futures selling led the spot market lower. It is a common pattern because speculators in futures market predominantly operate on margin/leverage compared to the spot (physical) market, where a higher proportion hold fully paid up positions.

© 2018 Monetary Metals

:

:

I’m not in the crystal ball gazing business so I don’t know where interest rates are headed. I do know that all value is subjective. I also think that it is not impossible that interest rates might rise. One possible mechanism would be that prices for goods and services are perceived to be rising by market participants and those participants then start to demand an interest premium when loaning money to account for the perceived “inflation premium.” This could possibly cause a rise in nominal rates. While I don’t disagree with Keith that this would wreak havoc with many governments and businesses through an increase in their borrowing costs and that this outcome could well be catastrophic for them, I’m not as sure that this “proves” that rising rates are impossible. I also admit that I don’t fully understand Keith’s ” Theory of Interest and Prices in Paper Currency.”

Thanks for another good post Keith. Your six part series, by the way, is excellent.

In terms of another theory as to how rates could keep moving up, i agree with your views on how a highly leveraged system such as what we have now will move to the black hole of zero rates and revulsion of money via that route. I do think it is important to explore the avenues that change time preference. To get to the holy grail of consistent rising rates (tight margins (check), rising wages, money stock (check) and velocity) a shift in liquidity preferences with distributional conflict must occur. The former, which is a velocity issue, relies on your already mentioned budgetary issues and goes into Cochranes FTPL where money holders forsee direct fed to treasury monetization of fiscal deficits and exit. But where too, as you have stated? Perhaps commodities (rising rates weaken the case for share buybacks and strengthen CAPEX – more plants and equip for companies to meet EPS targets and maybe short term but unsustainable profit increases) and hard goods for consumers as time pref rises. Rising wages could be anticipated with an anticipated change to a more liberal administration (Bernie Sanders and universal basic income or even trump and aggressive tax rebates if economy falters). Finally, there aren’t any cases of sustained i-rate rises in a high debt situation (which is really hyperinflation) that has not been preceded by war that destroys supplies and production facilities. Assuming we don’t have a real hot war, I am not sure that trade breakdown with China would have the same results but together with a series of natural disasters, an energy/food crisis (unlikely for some years as fracking helped immensely), and/or social tension could be enough to present the necessary distributional conflict for resources.

So generally I agree that higher sustained rates are unlikely unless the above events transpire.

In 1931 we had rising rates (10 Yr Us Treasury) with falling stocks.

The US is the world’s largest debtor nation. A rising interest rate cycle can occur simply from a widespread preference to stop using the dollar, concern that the national debt will not be repaid, or that the dollars themselves will not have value in the future.

The Federal Reserve itself could precipitate the crisis with their selling of treasury securities. If their bid to purchase during QE was a risk free opportunity for bond speculators to front run their purchases and drive the interest rate down – then their offer to sell is a similar incentive to front run their selling and drive interest rates up.

This Fed selling seems to be occuring right as the foolish budget deal to jack up spending will lead to even more increased debt issuance. With fed selling, budget deficits swelling and repayment concerns rising, there is every incentive for the bond market to revolt and drive up the interest rate. When unhindered bond markets sniff out that governments won’t be able to repay their debts, they are pretty good at spiking rates higher in short order (ex. Greece).

It can be argued that the Fed will simply reverse course, and resume QE, but the damage they could do beforehand in unquantifiable. There is also no guarantee that renewed QE would be “successful” again and may lead to the foreign exchange markets punishing the dollar (ie. gold going up rapidly) and leading to a dollar selling flurry by sovereign central banks that had been warehousing dollars and USD securities for decades. It is similiar to the thesis espoused by those like Peter Schiff.

This world view that all other currencies will fail first before the dollar, because they are “dollar derivatives” is flawed and very poorly justified. It relies on a “hunch” about how various independent thinkers will act in the future under extremely volatile and uncertain circumstances. Possibilities of reform or competition and displacement by other currencies are ignored. The rest of the world makes the useful products in the world and sends them to the US for their dollars. There is much greater incentive for the rest of the world to abandon the dollar rather than go down in ruin with the sinking ship.

My crystal ball says Keith is right, demand for credit is soft. Of course he’s referring to consumer credit. The demand for credit by governments, however, is as robust as ever. And increasing at a rapid rate.

Still, interest rates remain near 5000 year lows. At some point they are bound to go up, sure. That’s obvious. But odds for that kind of sustained material rise doesn’t appear to be high until markets begin to smell the stench of default. For clues to when that might begin, watch the high yield market. That will be first to go.

What do you think is the reason in the recent tight Gold Lease Bid-Offer Spreads?