Silver Smoking Gun to Stop Dishonest Dealing

Last week ZeroHedge reported on the amended London Silver Fixing Antitrust Litigation which included damaging chat logs provided by Deutsche Bank that reveal collusion between bullion bank traders to “shade”, “blade”, “muscle”, “job”, “spoof” and “snipe” the silver market.

While the amended complaint only provides selected examples from the 350,000 pages of documents and 75 audio tapes that the plaintiffs received as part of the settlement with Deutsche Bank, what has been provided shows cliques of traders who worked together against the interests of their clients.

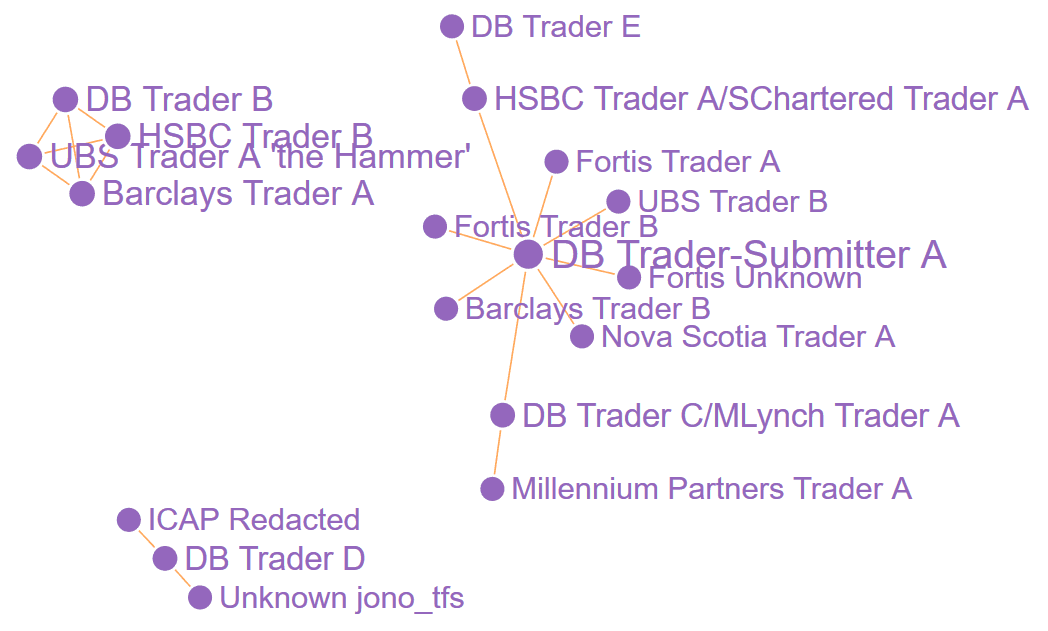

Below is a network map of these cliques, which shows every trader mentioned in the complaint with the lines indicating who chatted with whom (view the map online here).

The key ringleader is DB Trader-Submitter A (submitter refers to their role submitting orders into the London Fix) and this sort of hub and spoke model is common in social networks. The two persons with a slash and two banks in their name indicate that they moved banks during the period of the complaint. This is not uncommon in bullion banking since it is a small industry and would increase the risk of collusion between former workmates, something the management of the banks should have been alert to.

The lack of connection between these groups is likely due to them being in different timezones. The group of four in the top left corner are most likely in Singapore, given the use of Singlish terms like “lah” in the chats. The larger group is based mostly in London with one in New York, based on references in the complaint. The group of three at the bottom may be in Dubai, although that is speculation.

The chats have a jovial feel with traders calling each other “bro”, “dude” and “mates” and show no care for clients on the other end of their schemes: for example, Deutsche Bank Trader B talks about “wanna ramp it up like really just buy at mmkt and fk everyone so bad”. No doubt these chats will now be a lot more stilted as traders realise that collusive behaviour brings with it personal consequences like jail terms, as it did with LIBOR.

Nick Laird at goldchartsrus.com has collated all the chats in chronological order here with a chart of the silver price underneath to help put the chats in context of market price action at the time. In general, the chat logs show collusion to tactically/short-term manipulate the London Silver Fix and spot market (curiously, there is no mention of Comex futures, but the plaintiffs are only giving us a sample in this complaint).

With the Deutsche Bank chat logs showing a collusive network across banks, it would seem unlikely that the defendants will be able to refute the antitrust claim by the plaintiffs. The next question is that of damages. As it stands, the tactical nature of the manipulations means that the defendants are likely to argue that the members of the class action can only claim damages if they traded at the same time as the chat evidence shows market manipulation.

To cover the entire class and increase the damages, the plaintiffs need to show that the traders’ actions resulted in ongoing suppression of the silver price.

In the chats the traders do not explicitly indicate any plans to suppress the price on an ongoing, multi-day/month/year basis or reference having to manage a large naked futures short position (which many have said is necessary for ongoing price suppression to exist). Monetary Metals has written on the naked short theory in the past, noting that it is not supported by observation of prices as contracts approach first notice day. To implement such an ongoing suppression using futures, the bullion banks would need to roll their oversized short position by purchasing the expiring contract and shorting the next contract. Such massive buying of an expiring contract would cause the basis to rise, yet the opposite occurs – see here for more details.

Absent such explicit proof of suppression, the complaint masses a number of different econometric analyses to show that the London Silver Fix impacts other silver prices in the wider market.

The analysis does not start off well where, on page 40, the plaintiffs fall for the “correlation proves causation” fallacy claiming that “the prices of COMEX silver futures contracts are directly impacted by changes in the Fix price, which determines the value of the physical silver underlying each COMEX silver futures contract” on the basis of a regression analysis between futures closing prices and the Silver Fix of 99.85%. The defendants will be able to rebut such claims by referring to papers like London or New York: where and when does the gold price originate? which show that neither London (spot) nor New York (futures) are dominant in terms of price and that the dominant market switches from time to time.

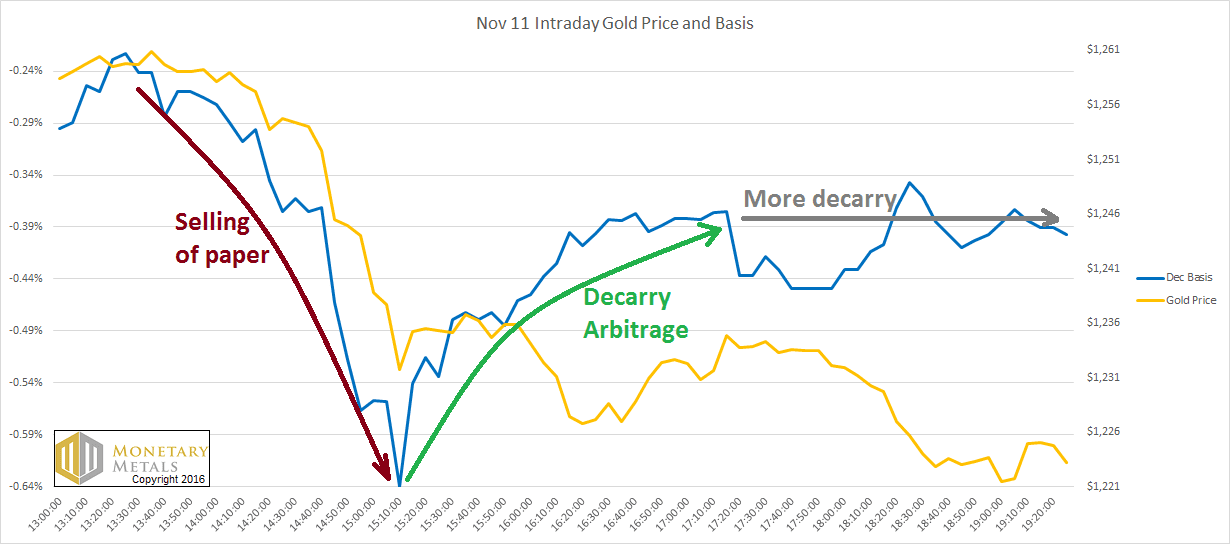

We feel the plaintiffs are on stronger footing when comparing spot and futures price movements around the fix (see page 71 onwards, figures 24 to 28). The plaintiffs’ show a few charts demonstrating a spot to futures linkage but we would suggest that to win the case the analysis would benefit from looking the spread between spot and futures markets, or the basis, which we report on each week. For an example of the application of basis to forensic price analysis, see our November 13 report where we show that the drop of $30 in the gold price around the London Fix on November 11 was driven by selling of futures as the gold basis began to fall before the price did (see below).

The final challenge for the plaintiffs is to prove that the impact of the banks’ manipulative actions persisted “well beyond the end of the Fixing Member’s daily conference call” (see pages 81-83). While the plaintiffs claim that this is proven because the mean of the cumulative unadjusted returns “on Down Days does not recover fully from the price drop that occurs at the start of the Silver Fix”, the very wide confidence interval implies that on a number of days it did recover. It will be interesting to see how the defendants respond to this crucial claim.

The Deutsche Bank chat logs have enabled the plaintiffs to get over the first huge hurdle of showing antitrust behaviour. The focus of media reports to-date on the colorful chats gives the impression this is a closed case but the lack of explicit chats discussing management of a large naked futures short position and/or plans to supress the price over months is unusual. One would expect that managing such a large ongoing supression would be the main focus of discussions between traders. It is possible that the plaintiffs may have withheld this evidence for strategic purposes but if not, this case may end up turning into a battle of the bookworms with academics arguing econometrics and questioning what does the “mean of the cumulative unadjusted returns” really mean.

Whichever way the case develops, bullion banks now have increased costs of supervising and managing the risks that precious metals trading desk “bros” might be looking to “fk” their clients. Combined with the potential that the “cost of doing business will jump – perhaps by 300% on one estimate” due to Basel 3 rules, some may decide to do a Deutsche Bank and pull out of the market. The result may be further consolidation in bullion banking and give regulators more justification to push those that remain out of “dark” OTC trading and on to “lit” exchanges.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!