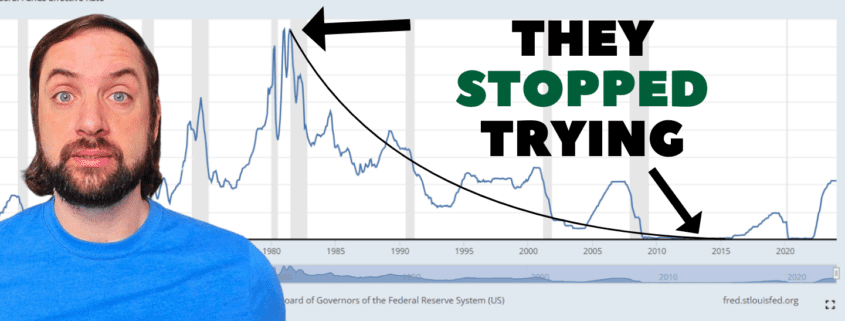

Jeff Snider: Their System is Malfunctioning

Jeff Snider joins the podcast to discusses the current economic climate, highlighting the disconnect between stock market performance and underlying economic indicators. Jeff explains how he sees gold and silver regaining their monetary status and why the Eurodollar system is no longer working.

Additional Resources

Earn a yield on gold, paid in gold

The Case for Gold Yield in Investment Portfolios

Podcast Chapters

00:00 – Jeff Snider

00:30 – Economic indicators

02:14 – Labor markets

04:34 – Economic cycles

05:30 – Impact of government debt

07:41 – Washington’s lack of incentive

09:57 – Global economic outlook

13:18 – Stock market disconnect

16:49 – Importance of market interest rates

21:18 – Demand for treasuries

26:54 – Eurodollar system replacement

31:16 – Benefits of a new monetary system

35:37 – The gold and silver ratio

38:07 – Eurodollar university

38:48 – Moneyness

39:22 – Earn a Yield on Gold, Paid in Gold!

Transcript

Ben Nadelstein:

Welcome back to the Gold Exchange podcast. My name is Ben Nadelstein. I’m joined by the one and only Jeff Snider from Euro Dollar University. Jeff, how are you doing today?

Jeff Snider:

Great, Ben. How are you?

Ben Nadelstein:

I’m doing great, Jeff. I wanted to start off with kind of an interesting question, which probably everyone has asked in some form or another, which is, why is the economy doing so well? Stock market is high. That euro dollar guy is screaming, everything’s going to be lit on fire. We’re heading towards a recession, and yet gold’s hitting all time highs. Stock markets are hitting all time highs. Jeff, aren’t you just some kind of doomer here? You think everything’s going to go to heck? Jeff, I’ll let you respond.

Jeff Snider:

Well, yeah, I don’t know how much of a doomer I am as far as I don’t think the world is going to crash or the world is going to end. But I understand the idea because, yes, I’m more pessimistic than maybe your average commentator for a variety of reasons, including the fact that gold is going up to a record high. To me that sounds like, hey, people are pretty nervous here about something. And of course, there are plenty of potential candidates and catalysts around the world, maybe not specifically United States, but when you look around the US economy, yeah, I understand why people are saying the economy is great because most people’s sense of it is, as you mentioned, the stock market, the unemployment rate and maybe GDP if they pay a little bit closer attention. And all three of those look absolutely terrific. But if you spend any more than just a few seconds on some of the other statistics, you realize that there’s a whole lot to be more pessimistic about starting with the labor market. I’m not even just talking about the statistics or the stats. I’m talking about people’s perceptions of the labor market.

You see mainstream media stories that have filled up so many pages recently about people can’t get a job. While we know that there’s been layoffs happening, it hasn’t been the type of layoffs that you would associate with a recession. But the other part of a recession is the fact that companies stop hiring. And in a lot of cases, they also cut back on workers hours. And those are two things that we have seen and have documented to a substantial degree over the last six, seven months and even going back further to last year. So while you can think of, okay, the economy looks good because there haven’t been layoffs. There has been at least a half a recession in the labor market. That’s not just about stories and anecdotes either. We have tons of data. Just yesterday, jolts came out with their figures on labor turnover. Hiring has absolutely fallen off. Quitting the great resignation. Well, that’s a distant memory. American workers know that there’s no point in quitting because there are no jobs available for them to go anywhere else. So as far as the economy goes, it doesn’t look like a recession, but it also doesn’t look like a boom either, which is why you keep seeing these stories in the Wall Street Journal, CNBC about how it feels like a recession, but it isn’t.

Well, maybe it feels like a recession because it actually more is than is not. And so what I would add is that the one thing that’s different in the United States economy this time isn’t just the layoffs, it’s the length of the cycle. The cycle has been especially prolonged and elongated for a variety of reasons. And that has led to this disconnect between what we expect to happen and what actually is unfolding. But when you look at the statistics, you look at the data, you look at the evidence, you listen to these stories, it’s very clear that this is still a cycle and that cycle is still heading in the wrong direction, the downside direction, even if it hasn’t caught up to GDP. And another issue, too, is that a lot of these statistics that we look at, they’re bifurcated. GDP looks great. GDI looks like a recession. The establishment survey looks great. The household survey looks like a recession. We got another one just recently, S P global PMIs look relatively okay, heading in the right direction. Ism says, nope, going in the wrong direction. So really it’s almost a pick and choose at this point, which is why I go back to the marketplace and the market view hasn’t changed this entire time.

And so more and more, the data ends up looking like the market. We hear more about troubles in the labor market, at least on the hiring side. It does suggest that the economy is very slowly, very gradually, still moving in that cyclical direction.

Ben Nadelstein:

And I think one point that you mentioned in another interview was that this cycle, even though it can take longer, and the question of when is obviously always a looming question. But the question of probabilities, of will this actually happen is much more certain because a business cycle is a business cycle. It ends where it ends, when the actual moment is obviously where all money is made. But it doesn’t seem like adding trillions of dollars to the debt and only getting a couple of billion in GDP means that the economy is healthy. Clearly there’s got to be some issue happening. And where do you see that kind of debt GDP question? Do you think they’re related at all? Do you think people should be worried about that? Or is it just more to the point of this bifurcation where some statistics look awesome while others look, well, not so great?

Jeff Snider:

Yeah, I think that’s the more immediate problem and impact is that how much of last year’s GDP was just the government doing what governments do? How much of that was the actual private economy being resilient and strong? You have to step back. I mean, think put yourself in the shoes of a business owner. Why would you be cutting hours? Why would you stop hiring workers if you thought the economy was just fine or if you thought that we were in a shallow, very temporary downturn and the recovery is going to be great in 2024, you would hire workers to get everybody back online to anticipate the recovery that’s coming. So the fact that businesses are telling us that there is something wrong, they aren’t willing to lay off workers just yet, and that may be the labor hoarding, that’s a unique aspect of the supply shock cycle. They aren’t willing to lay off workers, but they are definitely taking steps. We see the nominal incomes especially. So businesses are reacting to something. It may not be a full on, complete, obvious recession, but it is something like one. And so if that’s the underlying private economy case, maybe.

Certainly the government deficits and expenditures in the third quarter definitely played a role in the GDP number. But how much of an impact that has in the real economy? That’s completely unclear, but it’s something we should definitely think about. The other question, the more interesting one, the longer run question, the government’s finances and debts. Well, after the pandemic, politicians in the United States have figured out they have carte blanche here. They can spend as much as they absolutely want, and there’s no downside consequence to doing so, at least not one that they can directly identify. There obviously is downside consequences but nobody connects to one with the other. I mean, the more the government tries to allocate resources, the more the government gets involved, the worse it’s going to be in the long run, which they don’t care. Long run. That’s not our problem. So now that governments have figured out that they can issue as much debt as they want and interest rates are going to be relatively low, if the Fed would actually get out of the way, they would be even lower. Of course they’re going to do what politicians always do.

Politicians want to buy your vote. They’ve always wanted to buy your vote, and they have always tried to do so. They were just afraid that if they went too far, it would trigger the idea of vigilantism and the bond market would just blow up. Well, we’ve experimented over the last several years which suggested that many people said without the Federal Reserve, that would be the case. QE is the only reason the treasury rates haven’t gone through the roof. Well, that proved to not be the case, although we had ample proof before 2020 in the QE era and the experiences in the 2010s. But every excuse that was put forward, why interest rates were low and politicians were a little bit unsure about whether they would go that far, those have been completely obliterated in 2020 so far. So why would we expect Washington to get its house in order when they have no incentive to do so? That’s the bigger long run question, is it’s going to be up to the voters, which not too optimistic about that. It’s going to be up to the voters to rein in spending, which is absolutely something that needs to be something that needs to happen, because the long run consequences are much more dire than the immediate consequences of the government interfering in the economy and maybe making the statistics look a little bit better than they otherwise would have.

Ben Nadelstein:

And I think that’s such an important point, which is that the short run incentive for politicians is, hey, let’s paper over any crisis with more borrowing, more borrowing, more borrowing and more debt. And the immediate consequences are not obvious. While a lot of people, you know, there’s all this inflation, what about this record high inflation? And my argument would be that we had an incredible supply shock. I mean, we had a war in Ukraine. We had a global pandemic which shut down all business, all trade. So obviously that’s going to show up in higher prices. The monetary question, which has been going on since, like you mentioned, forever, has not really had much inflation. These bond vigilantes, these people who would bid up the price of these bonds are dead. I mean, if they’re alive, they’re very quiet and very small. If they ever, if they ever existed at all, they might be like a theoretical construct like unicorns or something like that. And so this has obviously led policymakers to either slowly or over time realize, hey, we can pretty much do whatever we want with no consequences. How are those no consequences affecting people outside of the United States?

Because inside of the United States feels like everything’s okay. What about outside the United States? Let’s talk about China, let’s talk about Europe, and let’s talk about the rest of the world.

Jeff Snider:

Well, the rest of the know, not directly a consequence of the United States, but more so their own problems related to the global economic circumstances. One of the reasons why I’m relatively pessimistic is the long run outlook for the global economy isn’t good, especially as we continue on this deglobalization trend, which began with a monetary crisis back in 2008. And that’s really the underlying fundamental case that I look at is that really nothing has changed. As you said, 2021 was about the supply side more than anything else. And while the supply side has normalized, guess what’s happening? Prices are themselves normalizing. That doesn’t mean they’re going to go back to where they were in 2020 or before 2020. That’s never going to happen. But they’ll stop rising because the artificial imbalances have largely been worked through. And so just to bring this back to what we were just talking about, as far as governments are concerned, they were afraid that they were the cause of the inflation or the cause of the consumer prices. They’re realizing, hey, that wasn’t us. We didn’t actually do that. That was more about the supply. Let’s issue more debt.

Isn’t that what Janet Yellen was basically saying last year? She’s like, hey, there doesn’t seem to be any consequences. So, sure, let’s issue a trillion dollars in debt in a single quarter. And guess what? There were no consequences. They actually did it. So as far as the government goes, consumer prices, the rest of the world really has to deal with that underlying circumstance, which is it looks like we’re going back into more of the 2010s for the 2020s after we got through the supply shock period, which is not a good thing to be in. That’s an enormous problem if you’re a place like China, which has built itself for many decades to be an economy that looked like the 2000s, not the. So in one respect, they’ve been trying to transform their own economy to prepare for the 2010s, moving forward into the having an enormous amount of difficulties doing so because of course they do. They have massive imbalances themselves that they have to take care of or at least try to manage and not let it get out of control like Japan in the 1980s and early 1990s. That’s what really drives and motivates the Chinese.

But there are also downstream consequences for China being stuck in that situation, because the rest of the global economy, that depends upon the Chinese to do those chinese types of growth things, they’re no longer happening. It causes strain in emerging markets. There are spillover impacts in finances. One of the things I’m concerned about is that chinese financial system and developers, they own a lot of properties outside of China, too. And as they run into liquidity problems inside of China, what are they going to do with their outside? Are they going to start fire sailing commercial real estate, which could actually trigger something happening in commercial real estate in the United States or Europe, which also has a commercial real estate bubble. And that’s another risk, too, because we also have the imbalances, some of the leftover imbalances from 2000 and 22,021 in financial markets. While we’ve dealt with the price aspect of consumer prices, we haven’t dealt with the financial prices yet, too. And that’s going to play out around the world. That’s not a specific US problem either. There’s a european issue, and it’s all interconnected Chinese, not just the Chinese, but asian markets as well.

So as we go forward in 2024, and I think as more economies fall into recession, we’ve already got Europe in recession. Japan fell into recession. Even though they’re talking about rate hikes and inflation, China continues to go get worse in its economy. That puts more pressure on all of these imbalances to maybe deal with them in ways that we’re not prepared for, that leaves us looking ahead at a lot more of the same, maybe even worse risks.

Ben Nadelstein:

And Jeff, you mentioned a point which is know the japanese economy is in a recession, and yet what about the japanese stock market? Can you talk a bit about the disconnect there? Some people say, well, if the economy is bad, that means the stock market, which is just kind of the economy, right? They’re the same thing. At the end of the day, they got to both be bad. Or if one is good, that means the other must good, right. If stocks are at all time high, the economy must be great. You don’t know what you’re talking about, Jeff. Right. These are correlated things. Stock market equals economy. What do you think about that?

Jeff Snider:

They are uncorrelated completely. You spend more than 2 seconds, you see how uncorrelated they are. And Japan has probably been the best example, which is why you’re bringing it up, the best example of uncorrelated share price behavior with economies, because the Nike has been rising since 2012, ever since Abenomics was introduced. So Abenomics has been a boon for share prices in Japan because they’ve been on basically a 45 degree ascent ever since. Not directly. I mean, they’ve taken some pauses here and there, but you can almost a straight line from Abenomics forward. So at the same time, Japan’s economy hasn’t changed. It’s been in the same stuck state ever since then. So the economy is like this and the stock market is like this, and we see that all around the world too. We see it in the United States. The S and P 500 has had a terrific 15 year run here, or 14 years after it got going after the great Recession. The US economy, on the other hand, has never recovered. It’s still in that same post 2008 state even after 2020. 2020 did help. It actually made it worse. Yet, share prices continue to go high.

And of course there are questions about what stock indexes are actually telling us anyway. Is it really all the stock market looking really good, or is it just a narrow slice of it? But even if it was, all the stock market stocks do not correlate to fundamental macroeconomic situations. Really, outside of recessions, that’s the only time where they really sync up, because in a recession you worry about, okay, maybe some companies are going to go bankrupt, so I’ll start selling stocks. That’s really the only direct link, or even really indirect link between the economy and share prices. So it’s not unusual in this section of economic and financial history that we’re living in to see share prices do one thing and the economy do something completely different. So if you’re looking for the stock market to tell you what’s happening in the economy, you’re looking at the wrong thing.

Ben Nadelstein:

Okay, Jeff, what should we be looking for in the economy? And what is maybe a signal? Obviously there’s the euro dollar market you mentioned. Gold hitting all time high actually might be a bad thing. Right? People are running to safety. And one thing you mentioned as well, which is that why is the Fed talking about rate cuts? If everything is so great, if everything’s so awesome, why not stay at 5%? Right? If the economy is super healthy, if the job market looks great if our GDP is growing. Well, let’s keep rates here. Obviously things are fine. Right? So what are some indicators investors should be looking at? People who want to understand macro, if not the stock market.

Jeff Snider:

Yeah, good place to start, Ben, as you point out, interest rates. Not Fed interest rates. Market interest rates. Because market interest rates are a fundamental signal of the economy. I know you’ll hear everybody say that. No, that’s not the case. The Fed has spoiled interest rate signals because of QE, because of how much they manipulate the short end of the curve, and it’s just not true. And the last couple of years have been a perfect demonstration that bond markets do operate on a fundamental basis, because all the excuses that have been used to dismiss these fundamental signals from interest rates have been absent the last couple of years. The Fed hasn’t been doing QE yet. What have interest rates done in the face of the US treasury supplying an unbelievable amount of debt? And yet interest rates have been steady to actually lower over the last couple of years. The Fed hikes its short term rates. Long term rates are steady. That’s not a good sign. If you understand that this fundamental signal is actually fundamental and that those fundamentals mean a high degree of demand for safety and liquidity, that’s not a good sign.

That’s really not. That’s not inflation. That’s not a soft landing. It sure as hell isn’t a no landing Goldilocks scenario. That’s the market saying as the supply shock continues to normalize, what are we actually normalizing to? We went through a period in the 2010s where it was basically like a prolonged depression, and then we got a supply shock that looked like, okay, we’re going to have a brand new paradigm where the economies are going to be robust forever. We got to worry more about inflation than anything, except as we go further and get further away from the supply shock, it looks like maybe we’re going to go back into the 2010s again. So how do we go from here to the. Suddenly the demand for safety and liquidity starts to make sense because that’s not necessarily a positive transition from the, everything’s great, red hot economy of 2021 to, holy crap, we’re back to 2011 all over again. That’s a potentially dicey and messy transition from one to the other. So the market, the fundamental signal from interest rates, they don’t tell you any of these details, but what they tell you is the background looks more demand for safety and liquidity over a longer period of time.

Therefore, that’s a lot like two thousand and tens. And we know that just fundamentally, interest rates are a combination of growth and inflation expectations. So when you factor what the short term curve, the Fed’s influence over the short term end of the curve is saying, there’s a really depressed signal from high demand of safety and liquidity, therefore lower growth and inflation expectations, which that doesn’t sound to me like everything that everybody’s talking about in a soft landing. And as you mentioned, why is the Fed talking about rate cuts? Why is the ECB talking about rate cuts? If everything was perfectly fine and we found out that the rates up around 5%, or five and a half percent, didn’t cause any damage to the economy, what possible reason would you have to cut them? And what the Fed will tell you is that, oh, well, once we’re confident that inflation is gone, we just want to take out a little bit of insurance in case our super ultra powerful rate hikes do go too far and they do trigger something like a recession. It’s just a little bit of insurance. It’s sort of like the 2019 ridiculous example where the same thing, it’s basically the same setup.

The Fed thought inflation was the greatest risk, started hiking rates in 2018, realized the economy was going in toward recession. A lot of economies around the world did fall in recession in 2019. And the Fed started out saying, well, we’re just cutting rates just to make sure. Of course, we never know how that would have turned out, but that’s the message that they’re going to sell us with the rate cuts. It’s just a little bit of insurance to make sure that everything’s just fine.

Ben Nadelstein:

And why do you see the demand for treasuries? It’s so broad, it’s so deep. It feels endless. You would think that a lot of people would say, what are treasuries at the end of the day, right? They’re just a promise to pay more dollars. And the guy who’s promising me is going into ever increasing amounts of debt. So why do you think treasuries still have this kind of almost endless appeal, even as we pump out more of them? And do you think that the rally in assets like bitcoin, rally in assets like gold? Do you think that’s some people waking up and saying, oh, my gosh, this debt is just eye watering, they’re never going to pay it back? Or do you think there’s just some other reasons here? Maybe people want some short term safety, some short term bets against the economy. Do you think that this kind of, like, this safety this trade, this trade to safe haven assets is slowly pushing away from T bills, or do you think now it’s t bills until we see something really drastically shift?

Jeff Snider:

Yeah, I think that’s really the case, as sad as that is. Again, I’m just the messenger here. I don’t recommend this. I’m certainly not an advocate for government going completely insane like this. But yeah, the Japanese have proven for as long as they’ve been doing it that, yes, there can be an endless demand for safety and liquidity. And the reason why it is treated as safety and liquidity has nothing to do with what you just proposed. It’s not about the federal government going broke. It’s about the use for these financial instruments in the way that they’re actually used, not just as financial collateral, but also perceptions of short run safe harbors in a short run crisis. If everybody goes into government debt, there’s no risk of default for the government debt, even as screwed up as their finances can be in the short run or the long run. So government debt is treated, and it should be government debt, but that’s just the way it developed. Government debt is treated in that fashion. Unless something else radically changes, then that’s going to be the way it is, and it can be the way it is for a very long period of time.

So the interesting question that you just raised is, is bitcoin or gold starting to move in the direction of becoming the alternate to that thing? As far as bitcoin goes? Well, we’ve seen this in bitcoin three times already. It’s actually more than three times, but three massive spikes like this. This has more to do with the quirks and the properties of bitcoin than it does any fundamental value in some fundamental uses, because there is no use for bitcoin right now in the financial system or the real economy. So bitcoin, I don’t think, has anything to do with the short run or even really the long run issues with the federal government and the debt. That’s just more about institutional acceptance of bitcoin as a portfolio asset, which is all it’s really doing. It’s becoming a value that people stick into their portfolios and they just look at it and say, hey, it’s great. The irony is they have to transfer it to fiat money in order to use the damn thing. So it’s like, okay, so no bitcoin, that’s not an alternative. That’s not becoming an alternative to the US system. The other option, gold, that you mentioned, I don’t think gold is doing the same thing either.

I think gold is going up because of the same reason that there’s so much demand for treasuries at the moment. People are saying, holy crap, there’s a lot of really bad stuff potentially happening here. And it’s not just one or another. It’s basically everywhere you look. China’s got a real estate bubble. There’s a commercial real estate bubble in the US. Europe is really. You can’t even list all of Europe’s problems, and that’s just the big ones. How about all of the problems around the rest of the world? I mean, geopolitics, what’s. Egypt is going bankrupt, Pakistan. I mean, just everywhere you look, there are issues. I know there’s always issues throughout history, but in the world, in this state currently, these issues are even more profound than they are in, say, normal times. So what do you want to do in case one of these things really does kick off something pretty big? Why not own a little bit of gold, just in case? And if you’re owning a little bit of gold and this person’s owning a little bit gold, they’re owning a little bit of gold. That tells you that there’s some substantial degree of maybe not consensus, but moving toward a consensus that there is every reason to be concerned that some of these things are indeed very troubling developments and can become even more troubling as it goes.

So gold, to me, I think it’s more about the safety hedge than anything else at the moment.

Ben Nadelstein:

I do think one interesting thing to note, which is obviously there’s this flight to safety. Gold benefits from that. But what’s even more interesting, other than for clients of monetary metals who do earn a yield on gold, gold is usually seen as an asset that has no yield at all. And so gold hitting all time highs against T bills paying 5%, or CDs paying 5%, is even more interesting than gold hitting all time highs in a zero interest rate policy environment.

Jeff Snider:

That is a huge, powerful signal that something people should be paying attention to, especially those who aren’t. Your clients are smart enough to realize that you can get an interest rate on gold. Look at the behavior of gold over the last couple of years. It spiked and surged right up into what, August of 2020? Which made sense. Pandemic worldwide shutdowns. We don’t know how this is going to let’s buy gold. And then during the period when CPI started accelerating, and this long standing idea that gold is an inflation hedge when it’s really not, as the CPIs are accelerating gold was sideways to a little bit lower, which was somewhat impressive, especially as interest rates started to move up. You would expect that given the fact that gold, for most people outside of your clients, doesn’t pay an interest rate, gold should have collapsed. It should have gone back down to what, thousand or even less? Given the aggressive move in interest rates, you would expect that to happen, and it didn’t. Instead, gold kind of hung in there until October of 2022. October, November 2022, it starts to rise again. At the same time, you see all sorts of fireworks in bond markets.

Bond curves all over the world, especially like the german curve. We’d never seen the german curve invert like it did in October 2022. So there’s a corresponding relationship there. As those curves have continued to develop in the same way, gold has gotten stronger and stronger and stronger, regardless of interest rates, in the face of rising real interest rates, which are supposed to be one of the biggest correlations. So you have to ask, what the hell is going on here? Everything that we thought about gold, it seems to be hanging in for one reason or another. So to me, it makes perfect sense when you look at what the curves have been saying and what gold is saying in that respect. Those two are actually, I hate to say it, two sides of the same coin.

Ben Nadelstein:

How do you see the rest of this playing out? So, obviously, there’s this short term moment, right? Maybe assets like gold and bitcoin are getting a bid here, but just because of this kind of short term question of, will there be a recession? Are we in one right now? Will stock markets kind of ravine into a cave down here where GDP really is? Will people start doing this? But these are short term questions in terms of the medium and long term. Do you see that these euro dollar system, the dollar kind of whole universe, is it strengthening? Is it weakening? Has there been a break? Do you think something happened in 2008 that just set us on a different course than we were on before? Or do you think 1971 was the real moment when things changed or something before that? Do you see that we’re on a similar trajectory? And where do you see that trajectory going past where maybe this short term volatility starts?

Jeff Snider:

Yeah, the Eurodollar system needs to be replaced. It’s been malfunctioning since August 9 of 2010. You actually put a date on it. And really, the big picture, the banking system realized that the way it was operating and keeping this global ledger just wasn’t going to work going forward. So there’s really no going back to that. The problem is we don’t have a solution available to transition from a euro dollar based monetary global reserve system to something else. And so that’s where cryptocurrencies are coming from, is the idea that we can develop the something else. And I know there’s a lot of people working in the gold market to try to transition back in that direction too, because there does need to be a something else. The problem is we have to have something else that actually undertakes and overtakes the euro dollar’s capacity to do what it is that it’s supposed to do as a reserve currency, which is make it widely available, flexible, and widely acceptable. Which, I mean, gold has some of those properties, cryptocurrencies might have other those properties, but neither of those are anywhere close to being able to undertake the reach and the functionality of the eurodollar.

So we’re stuck with this stupid thing until the technology progresses, or God forbid, something big happens and forces a transition, which I don’t necessarily think is the case. I do think there’s a very optimistic path forward here, which is that as all these alternative monetary systems continue to be developed, they get better and better and better and better, and do more and more and more, and are acceptable in more and more places. And just like the euro dollar took over in the really before then, but sixty s and seventy s, we don’t really notice before the end. One day you look around and the US dollar is still there. The euro dollar is kind of still there, but we’re also using other forms of money that are actually more important to us than the euro dollar used to be. And we don’t really notice that. There was a transition. We just kind of transitioned and the world started flourishing again. And there was no big crisis moment that everybody said, okay, this is what’s happening. That’s, I think, the most optimistic way forward. The problem, Ben, as you know, is how much longer do we have before these other alternatives develop enough capacity and capabilities to do all those things?

That’s what we really need to worry about, because as we continue in the same eurodollar era, it leads to more economic stress, more financial volatility, more inequality. The great migration, where does that come from? Well, that’s a post 2008 reality of economies around the world that are falling apart. So, I mean, there are all sorts of real world, as well as monetary and financial consequences to this situation. And it’s like, which one is going to get there first? Are we going to get these alternative solutions to come up online in the way we need them to or are we going to continue to go too far and it leads to something breaking? It’s impossible to say for sure. So on the one hand, there’s every reason to be optimistic. On the other hand, there is some doom and gloom to the trajectory that we’re on now. But at the end of the day, the problem is we have a monetary system that doesn’t work and we have monetary officials and politicians that either don’t know it or they don’t want to admit it. So they’re no help either, because you won’t hear Jay Powell saying, yeah, we need to develop some alternative currency system.

He’s never going to say that. So we have to do it outside, which makes it even more challenging, which makes more difficult and more of a prolonged process. But there’s a good way forward and there’s still a bad way forward and there’s lots of stuff in between.

Ben Nadelstein:

And as we begin to wrap up here, I do like that there’s this kind of positive note. Obviously, monetary metals were hoping to be one of those positive impacts. But I want people to think about this, right? If you’re on the Titanic and it’s sinking, everyone can agree that the Titanic is sinking. But if the life rafts are 75ft on the water, you’re jumping onto concrete, right? Like you’re going to die just by hitting the life rafts. You need to have the life raft one step, ideally right off the boat, or it’s actually on the boat, right? And there’s a better boat that comes right nearby and everyone just hops over. Right? So you need to have these kind of payment mechanisms. You need to have this kind of like, medium of exchange question answered. You need to have this. Well, how are we denominating our currency, right, as a unit of account? There’s lots of these things. As, like you mentioned in one of our episodes, the plumbing of the financial system is so complex and integrated and obviously globally there, that if you’re just going to say, well, everyone’s going to start doing XYZ, that’s a big.

Just doing a lot, a lot, a lot of work. So maybe before we end here, what are some things you think a new monetary system should be focused on? You can talk about gold, you can talk about crypto. What are some kind of barriers, some challenges you think should be faced? And what do you think some benefits you might see from a gold system or even a crypto system?

Jeff Snider:

Well, stability would be one. Right, let’s start with stability. The euro dollar is inherently unstable. It just appeared to be stable for a long period of time because it was working. It was working in a commercial GDP growth around the world sense, but it was always inherently unstable. That was one of the flaws. So yeah, let’s fix the stability issue. But as far as a new monetary system, I think the focus should always be on commerce. Money itself is not the point. Money is a tool and is a tool with a specific. Well, a couple of specific purposes. But its true specific purpose is to allow a specialized economy to be continuously specialized. It allows it to be efficient. So money isn’t wealth. Money doesn’t create wealth. It is a tool that greases the wheels. It’s a little bit more important than the grease. It’s actually maybe the wheels. But essentially that’s the point. Money should be focused on making commerce efficient and sustainable in order to do that. Stability is one part, but it also needs, as I said, flexibility, reach, and those types of things. There needs to be that focus on medium of exchange that I don’t think is always present in some of these alternative, I mean, bitcoin is a perfect example.

Bitcoiners could not possibly care about it being a medium for them. It’s only a store of value. And they have it in their minds that money has to be a store of value first before it becomes a medium. When history shows, I mean, deposit money was a medium first. Euro dollars was a medium first, a commercial focused medium of exchange that has some stable properties in it. Okay, sign me up for that. I think that’s the way we need to work toward. But those are difficult things to put together because medium requires some flexibility, some adjustment functions, and stability is kind of rigidity. So there are some big picture and some small scale questions that need to be solved in order to get to where we want it to again. I mean, we need something to happen, and there is a pathway to do all this. There’s so much technology and there’s so many. I was just at the ETH conference in Denver just recently, and there are so many smart people, forget about crypto, just working on these monetary issues. Whereas before everybody, I go back a long way, I remember the 1990s, you talk about money, nobody cared.

Nobody had any interest in it. It was all just, hey, the Fed’s got it covered. What do we care? So in that sense, there’s every reason to be optimistic. There are a lot of people, there’s a lot of resources, there’s a lot of talent, yourselves included, working on these problems. And eventually you’re going to find a solution. We’re going to find our way forward. And I think just to finish up one last property or one last thing I would like to see is we don’t necessarily need one form of currency. How about competing forms of currency? If the free market has taught us anything, competition is always a good thing, so why not competition and money too? I think that would be a tremendous way forward. So if all of these things could come together, and I think they will at some point, just hope it’s before it gets too late with the rest of everything, all these things come together, there’s every reason to be long run optimistic.

Ben Nadelstein:

I did have a question for you. As monetary economics started to happen, right. People, just out of their own self interest, these incentives came where money was not only just gold, but also silver. Right? So for large transactions, there was gold, smaller transactions there was silver, and there actually became this ratio between gold and silver where you could kind of trade them back and forth. Obviously, governments imposed stricter ratios, which obviously led to things like Russia. And that obviously never works.

Jeff Snider:

That didn’t work too well.

Ben Nadelstein:

No, that worked horribly. So, final question for you here, and this is just maybe of interest to clients of monetary metals. Do you see a reversion back to this historical ratio between gold and silver? Or do you think that there’s kind of this demonetization of silver, and soon silver is going to have its own story, the same way that platinum and copper, they have some relation to gold. But it might silver start look to be a more commercial metal instead of a monetary metal or just a precious metals like platinum? Or do you see that silver really does kind of hold on to its monetary status?

Jeff Snider:

I think if gold were able to move closer to becoming more useful money again, I think you would see silver start to develop its monetary properties because there would be a need for it, just the same way that historically it was the lower denomination, everyday use coin. So that would be the case. And I think that’s why silver, like copper and all the other metals have they become industrial commodities. And so they mostly reflect industrial prices, which is. I talked about this recently. The gold to silver ratio has gotten way out of line over the last, what, 5678 years, because silver is treated almost specifically as an industrial metal, which makes sense. It’s being used a lot in some of those electronic capacities, whereas gold has done really well as a precious metal hedge, but not necessarily a monetary metal. And silver hasn’t been able to follow along. Neither has copper either. So, yeah, I think silver and copper and some of the other metals are more strictly industrial commodities. But if gold were to get itself back into the monetary game, I think there would definitely be a need. And of course, if gold prices continue to go up, then silver prices would have to catch up, which would mean a huge move in silver, which then would probably create a need for copper to come along behind.

So that’s really a long run key there, too. But until we get to that point, they have shown repeatedly that they’re industrial commodities first and foremost.

Ben Nadelstein:

Jeff, it has been an awesome conversation with you. I’ve seen you guys have done some incredible webinars, commercial real estate, eurodollar stuff. Where can people find more? Jeff Snider, more eurodollar information? I mean, people obviously can’t get enough of you. There’s the YouTube channel. We just want more. Jeff Snider where can we find you?

Jeff Snider:

It’s Eurodollar University, both as the YouTube channel title as well as the website, which is just Eurodollar university. We’ve got memberships and subscriptions available there where we go into all of these monetary details, the history, the background about the eurodollar system, what it is, why it matters, what is a global reserve currency, really need to do that kind of thing? So that’s Eurodollar university. And again, as you said, Ben, the YouTube channel is Eurodollar University, too.

Ben Nadelstein:

Jeff, what’s a question I should be asking all future guests of the Gold Exchange podcast as we move forward?

Jeff Snider:

Oh, boy, that’s a tough question because you could ask any number of things. Just for my own sort of area of expertise, I guess I would say try to find out their appreciation and their ability to understand how useful money needs to be in order to be useful money. In other words, what’s the moneyness aspect of any instrument? It’s really about usability and medium of exchange. So some kind of question along those lines

Ben Nadelstein:

Jeff, thank you so much for coming on the Gold Exchange podcast. I’m sure we’ll have to have you back again soon.

Jeff Snider:

My pleasure, Ben. Thanks for having me!

Additional Resources for Earning Interest in Gold

If you’d like to learn more about how to earn interest on gold with Monetary Metals, check out the following resources:

In this paper, we look at how conventional gold holdings stack up to Monetary Metals Investments, which offer a Yield on Gold, Paid in Gold®. We compare retail coins, vault storage, the popular ETF – GLD, and mining stocks against Monetary Metals’ True Gold Leases.

The Case for Gold Yield in Investment Portfolios

Adding gold to a diversified portfolio of assets reduces volatility and increases returns. But how much and what about the ongoing costs? What changes when gold pays a yield? This paper answers those questions using data going back to 1972.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!