Liquidity Preference Rising, Report 3 Jun 2018

Picture a scene in one of those action moves. Two guys are fighting for control over the steering wheel. The car is going 75mph, the road is narrow, and there is a drop over a cliff on one side. And there are lots of sharp curves.

Central Planning

This is a pretty good picture of the action at our central banks. Desperate men are fighting for who gets control of the monetary steering wheel, and for which rules to use to determine when to turn left and when to turn right. One side wants central planning with discretion and the other wants central planning with rules. Among the latter, a debate now rages whether to use inflation, GDP, or another measure.

For decades, the central banks have centrally planned our economy. Just as the guys fighting in the car don’t notice the abyss they keep not falling into, these central planners don’t notice the falling interest rate.

Perhaps it’s because they scoff at the actual rate at which actual lenders lend actual dollars to actual borrowers in the actual market. This, they dismiss as the mere nominal rate. But they calculate inflation, averaging apples and oranges, gasoline, and housing. Then they subtract inflation from nominal interest to get the real interest rate. That’s what they call this fictitious number, at which no one lends and no one borrows. Their real rate probably isn’t pathologically falling, the way the nominal rate is…

Wait, let’s look.

Oops! Yes, it is. It’s also falling. Huh.

Well, we must throw our hands up at this point. Mainstream economists don’t address falling rates, either the cause or the effects. It’s the grand inconvenient truth of our very model of a modern monetary marvel (with due apologies to Gilbert and Sullivan).

Anyways, while they struggle to control the wheel of the falling monetary system, there is something else that they miss. So let’s discuss it today.

Central planning renders economic planning impossible. It is government forcing outcomes that it wants, onto people who don’t. Central planning is nothing less than a negation of economics as such. It replaces all of the rules of economics, all of the incenfallintives, the hopes, the plans, and the human actions. With a gun. It should not be controversial in 2018 that central planning doesn’t work.

This principle is reasonably well understood, when applied to corn. Corn has an annual cycle. Production and distribution are pretty simple mechanically. Yet every socialist state that tries to plan corn starves its people. Some, like Venezuela and North Korea, still starve their people today.

Credit has a cycle that even the proponents of monetary planning admit can be decades. It is anything but simple or mechanical. Yet many otherwise free marketers advocate a central bank to manage the economy, “to give it a little nudge when it needs it”. They debate only which rule to use in planning. Should the nudge be based on faltering consumer prices, or should it be based on faltering growth of GDP? Or maybe a newer measure instead of GDP, such as Gross Output?

All such debate is beside the point.

Central monetary planning has a few unique features that don’t occur in central corn planning. We have discussed the falling interest rate many times. And today we see that even their so called real rate is falling. And falling. And falling, for over three decades.

As an aside, we acknowledge that the Fed does not dictate the yield on the 10-year bond. However, it has a legal monopoly on the issuance of currency, which is granted the status of legal tender. It is given powers to manipulate the bond market that no private firm would ever have. The Fed establishes a dynamic characterized by positive feedback and resonance. Positive feedback leads to runaway phenomena, like Jimi Hendrix holding his guitar up to the amplifier, or a nuclear fission bomb. Resonance leads to self-reinforcing action, such as the waves that collapsed the Tacoma Narrows Bridge.

The net result is that the interest rate is now on a pathological trajectory.

Everyone knows what happens if a central planner sets the price of corn below the cost to produce it. Farmers stop growing corn, while the hungry people increase their demand. In short, there is a shortage.

What happens if the price of credit is pushed down? There is not a cost of production, a saver’s cost to grant credit per se. So we cannot make the comparison as for corn.

Liquidity Preference

However, savers do have time preference. King Canute could not make the tide roll back. The Church could not make the Sun orbit the Earth. And the Fed cannot make people stop discounting the future. However, Canute could order his men to swing their swords at the surf. The Church could burn men at the stake for daring to say that the Earth revolves around the Sun. And in the Fed’s regime, the interest rate can fall below the time preference of many investors.

We frame it this way, to emphasize that interest is how people discount the future. We are living beings, and we must sustain our lives every minute of every day. To be alive in one year means being alive tomorrow, the next day, next week, next month, etc. We are also mortal beings. We can die. And we are not omniscient. We are not given knowledge of what will come.

Time preference comes from being alive, being mortal, and being fallible. We must, necessarily value money in the hand more highly than money to be paid in a year or in 10 years.

However, in our centrally planned credit market, the actual price of credit (forget the so called real rate, we refer to the actual rate that an investor earns) can be pushed below one’s time preference. What do investors do when this happens?

What they cannot do is proper economic planning. They are impaired in their ability to deploy resources to obtain a return in the future. When interest is less than their time preference, their very calculations depend on rubbish values. It would be as if one was an engineer living under a law that set the value of PI by fiat (Indiana almost did this). A circle is not square, but the Indiana government nearly forced people to act as if it were. Or like opening a complex spread sheet of your company’s business model, and typing 0 in a few random, but important, cells.

Investing, especially in long-range projects is harder and harder to justify. We are not referring to those high-profile companies who attract millions from venture capitalists. In the first place, there are very few companies that get this kind of investment. And it must be noted, that the venture capital firms have been moving steadily towards later-stage companies. VCs have a business model of flipping companies. They buy, help accelerate, and then look for an exit in a few years.

Anyways, this inverts the discussion that we want to have. Most investors don’t run a venture capital firm, nor are they angel investors (and they shouldn’t be). So what do the majority of investors do when their time preference is violated?

They can’t get adequate yield. So what do they turn to? What is the surrogate that substitutes for yield?

Liquidity. The investor figures, if he can’t earn 5% (or whatever he believes is reasonable for a 10-year investment), then at least he will own something that can be sold at a moment’s notice. At the push of a button.

Incidentally, we have seen behavior this with two kinds of investors. The first hears our pitch to pay interest on his gold, and asks, “How long is the lockup?” Our typical deal is one year. “Oh, well, no thanks. I want to stay liquid.” These investors are expressing a preference to spend 0.75% for storage, rather than be paid 2 or 3% interest. Why? The price of gold might go up or it might go down. They might want to take profits or need to cut losses (as they measure it, in the Master’s Money).

The second type heard the pitch for Monetary Metals equity (we just closed a capital raise). They know and agree with our thesis that our monetary system is failing, that the world needs a viable gold alternative, that paying interest on gold is the key, that we have hit major milestones, and are scaling our business. Yet several declined, saying “well I put my money into bitcoin.” The primary issue with them, is not that bitcoin is going down and Monetary Metals is going up (that is a problem for them, but not the primary one).

The problem is that their liquidity preference is so high that they won’t let themselves invest, instead preferring to speculate. This is a problem for the world. Monetary Metals got the funding it needs, because we know a lot of people and have an extraordinary vision. How many businesses ought to get funding, but don’t? Keith wrote about the paradox of flooding big public corporations with dirt cheap credit, while starving the smaller ones who need it in The Credit Gradient.

Liquidity preference becomes the dominant force, when time preference is obliterated. Liquidity becomes the surrogate for yield. And speculation supplants investment.

Markets become dominated by restless churn. Witness bitcoin going from a few hundred dollars to $20,000 in a bit over a year. Then down to $6,000, then bounced, and now who knows?

The people do not repudiate the dollar. This is not Mises’ crack-up boom yet. This is not a one-way trip for commodities prices to run to infinity. This is trading hoping to find an asset that’s going up, and preferring to put money only into things that allow money to be pulled out quick. This is the opposite of a rejection of the dollar, it is a tactic to make more dollars. Not by financing something productive or innovative, but by betting ahead of the other bettors, and being savvy and nimble to withdraw one’s bet at the top.

The world needs a better system. Liquidity is not a proper substitute for yield, as speculation does not serve the same function as investment.

Supply and Demand Fundamentals

Last week, we showed a graph of rising open interest in crude oil futures. From this, we inferred—incorrectly as it turns out—that the basis must be rising. Why else, we asked, would market makers carry more and more oil?

We are grateful to Peter Tenebrarum at Acting Man and Steve Saville at The Speculative Investor for setting us straight. According to their data, oil has been in backwardation for many months. The rising open interest position is due to, among other players, increased hedging by producers.

The gold market is unique, in that all of the gold produced over thousands of years is still in human hands. All of that metal is potential supply, at the right price and under the right conditions. And virtually all of the supply to the market today is existing gold stocks. Mine production is very small compared to the total stocks.

In our oil assessment, we implicitly accepted this unique gold market condition as being true for oil. We assumed that new contracts are carry trades made by market makers. However it is obvious that, as the price rises, oil producers ramp up production. And this creates a need to hedge. They sell their production forward. What is true for gold isn’t true for oil.

Speculators were buying futures, figuring to profit from a rising price as they saw the backwardation (they were right until May 22). Thus there were two sides adding to their position sizes.

That is a bit of an oversimplification, but we will leave it to others who study the oil market to provide full analysis. Anyways, before we get back to our regular scheduled programming, gold and silver, we said something last week that we stand behind:

One, the long-term trend is still falling interest rates.

Two, commodity prices correlate (and are caused by) interest rates. Rising rates causes rising prices, and falling rates causes falling prices for reasons Keith spells out in his Theory of Interest and Prices.

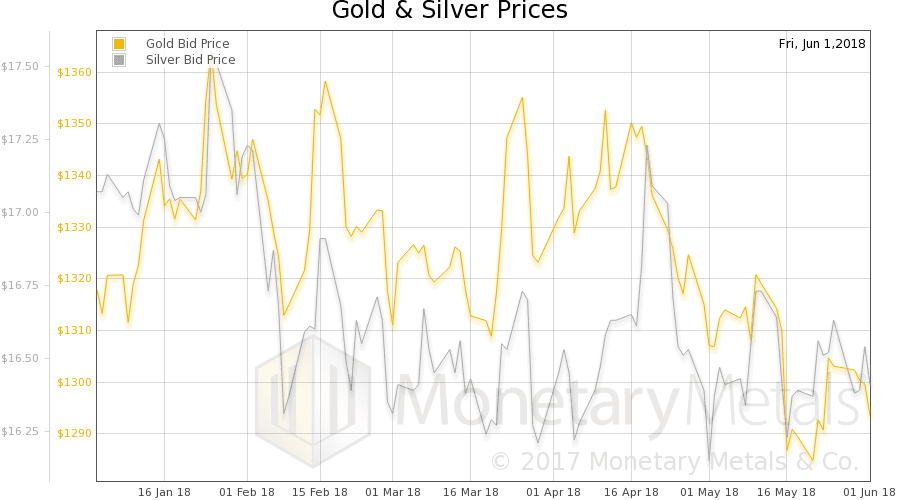

The prices of gold and silver, measured in the inflationary and unstable US dollar that some gold bugs still insist will collapse on July 1, but nevertheless use to measure gold and silver, fell $9 and $0.09 respectively.

Measured in crude oil, whose supply and demand are both subject to massive gyrations due to the unstable interest rate in the dollar, gold rose from 19.18 barrels to 19.65. And silver rose from 0.24 barrels to 0.25 barrels.

All joking aside, we will show the only true picture of the gold and silver fundamentals. But first, here is the chart of the prices of gold and silver.

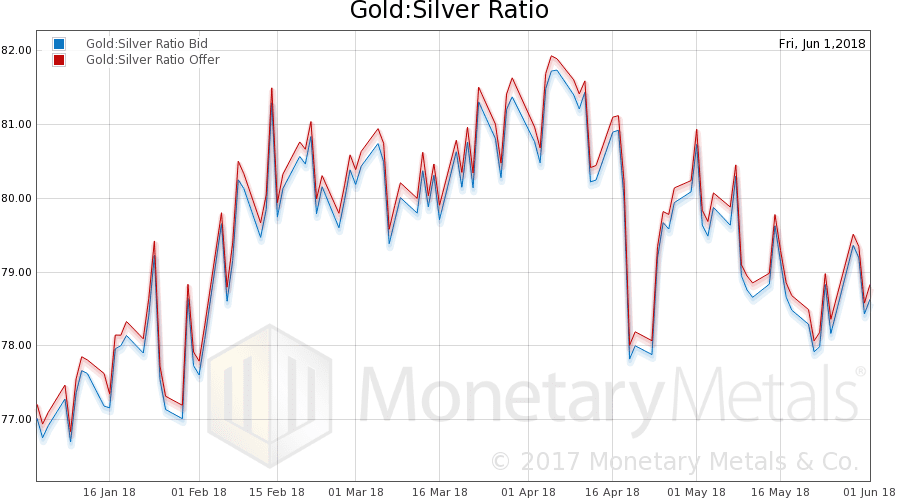

Next, this is a graph of the gold price measured in silver, otherwise known as the gold to silver ratio (see here for an explanation of bid and offer prices for the ratio). It was all but unchanged.

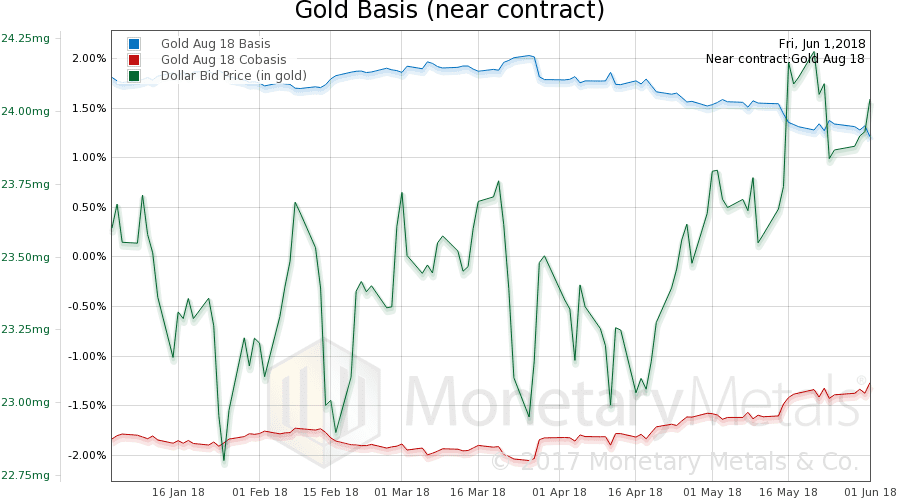

Here is the gold graph showing gold basis, cobasis and the price of the dollar in terms of gold price.

The price of the dollar rose (inverse of the price of gold, measured in dollars). Along with this, the scarcity of gold increased a bit.

The Monetary Metals Gold Fundamental Price fell $12 this week to $1,386.

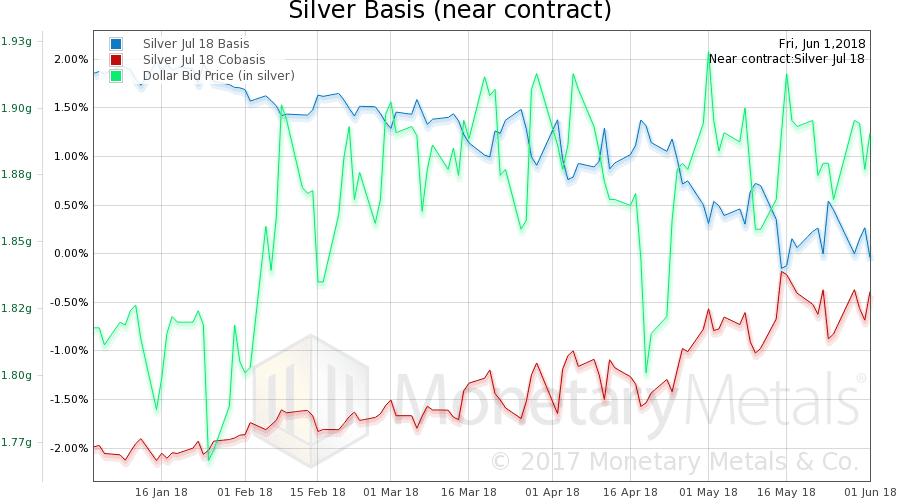

Now let’s look at silver.

The same thing happened in silver, except the rise in scarcity was larger than gold. At least in the near contract. The silver basis continuous shows a much small move up in the cobasis.

The Monetary Metals Silver Fundamental Price rose 9 cents to $17.51.

© 2018 Monetary Metals

There’s another reason people won’t invest. It’s called RISK. Fear of loss. Simply put, because risk can’t be completely eliminated, it just hangs there over the investor’s head, haunting him. In other words, he wonders whether he’ll ever get his gold back after all. Will the insurance really cover a loss as planned… or will they too fall victim to a coming tidal wave of defaults? Is a meager 2.5% really enough to compensate for that sort of risk? Everybody asks that question, and for many apparently the answer is no.

Sure, time preference is important. But “speculating” is a harsh word to use for someone who places value on a core insurance position that depends on no-one, and thus has zero counterparty risk. That is NOT what MM is offering.

lol… dude, that’s harsh! You mean 2.5 doesn’t turn you on?

fascinating… Fundamental equal or perhaps under bullion. That’s a switch!