The Federal Counterfeiter

Suppose you wanted to run an enterprise the right way (we know, we know, this is pretty far-out fiction, but bear with us). And, your enterprise has a $1 million dollar piece of equipment that wears out after 10 years. You must set aside $100,000 a year, so that you have $1 million at the end of 10 years when the equipment needs replacing. There’s a word, now archaic, to describe the account in which you set aside this money. From Wikipedia:

“A sinking fund is a fund established by an economic entity by setting aside revenue over a period of time to fund a future capital expense, or repayment of a long-term debt.”

Whether you borrowed the money to buy the equipment or whether you had equity capital to pay for it, the principle is the same. Unless your business is sinking, i.e. consuming its capital, you must replace your assets when they wear out. You must set aside a sinking fund.

The money to buy a replacement asset does not come out of thin air when the old asset finally bites the dust. It must be accumulated over the life of the asset.

Note that, even if you financed the asset with a loan, you still need to set aside $100,000 a year (beyond the interest payment). This is to pay off the loan itself.

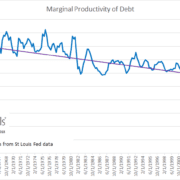

The Federal Reserve is not just a counterfeiter, it is also the enabler of counterfeiters. Corporations accumulate debt, which means that instead of paying loans when the asset is worn out, they just effectively borrow more. Two ingredients are necessary to enable them to get away with this. And these ingredients are served up by the Fed.

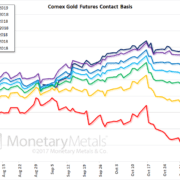

One is the falling interest rate. At a lower interest rate, a company can service more debt—we’re not talking about repayment of principal, only the interest. If the interest rate falls enough, the corporation can service both the debt to finance the worn-out asset plus the debt to finance its replacement for the same monthly payment. If the interest rate is falling at the right rate, it makes it possible for borrowers to keep on accumulating debt.

Two is extremely tolerant lenders. Normally, lenders don’t want to lend to companies who can’t repay their loans and just sink deeper and deeper into debt. But the regime of the Federal Reserve disenfranchises the lenders. It subjects them to ever-diminishing returns (i.e. falling interest rates). More fundamentally than that, it removes their choice to lend or not to lend. To hold a dollar balance is to be a lender, and the only choices left are duration and credit risk. And, as the interest rate falls further, everyone is pushed towards greater duration and greater risk. They take these risks, not because their “appetite” is increasing, but because that’s the only way to earn their required minimum rate of return.

Witness the obscenity known as the Payment in Kind bond (PIK).

A PIK bond explicitly repudiates the principle of a sinking fund. The borrower is not only not setting aside cash to repay the principle—it is going deeper into debt with each interest payment due! A PIK tells the lender up front that the debt shall not be amortized. This is not a proper way to run a company, but consider that the primary victim of this abuse is the lender.

The retort is that the lender is willing. Otherwise, he would not buy the bond. That’s true as far as it goes, the way every choice made in government-controlled markets is still a choice. And, no doubt lenders regard this as a convenience. They can have the full principal amount earning interest for them until maturity (and even have the interest earning interest), and then if they wish they can roll into the next PIK.

The price paid by the lender for this convenience is that it is a willing party to a fraud. That is, the borrower lacks the means or intent to repay its indebtedness, which makes this a counterfeit credit. We identify four elements necessary for proper credit: (1) the lender knows he is lending, (2) the lender is willing to lend, (3) the borrower has the means to repay, and (4) the borrower has the intent to pay. A borrower who sets aside no sinking fund is likely in violation of principles #3 and #4.

Lenders should be more concerned with the soundness of the businesses to whom they lend, and less concerned with other factors (e.g. ease of calculating the portfolio model). The principal of the sinking fund, i.e. of paying the full price of each capital asset during its lifetime, is always true regardless of whether the business is a Mom-and-Pop or a major corporation. The principal of sinking deeper and deeper into debt, i.e. of consuming capital, is also the same regardless of the size of the company.

The process of consumption of capital has a finite terminus. When the capital runs out, when the seed corn is all eaten, then there’s nothing left and the fraud can be maintained no longer. The equity holders, of course, lose everything. And, the lenders suffer dreadful losses as well.

Now, let’s tie this with one more connection to irredeemable currency. In addition to disenfranchising savers, irredeemable currency has another property. It removes the extinguisher of debt (i.e., gold). Without such an extinguisher, there is no way to pay off debt, on net. Yes, yes, it is possible for an individual debtor to get himself out of debt. What is not possible is for debtors in aggregate to reduce their debt, much less pay it off.

In other words, debtors are both prevented from paying off their debts and enabled to just add more at the same cost. Meanwhile, savers are forced into the open arms of these debtors. They are deprived of any real choice and, besides, this kind of debt is terribly convenient.

Investing in gold, either back during the gold standard or now, empowers the lender. This is because gold offers the lender a choice which is not possible with irredeemable paper currency. It’s always an option—and a very good one, at that—to simply hoard one’s gold. One is better off with gold under the mattress than with gold lent to a company that’s sinking in an orgy of capital consumption.

Too many people think of the gold standard primarily in terms of the idea of quantity. It is true that the quantity of irredeemable credit is boundless and the quantity of physical gold is not. However, we present a contrast between these two systems in light of the sinking fund in order to show that the principal difference is not quantity but honesty.

The regime of irredeemable currency is inherently dishonest.

Observant readers may have noticed that we have used the word “sinking” in what seems to be two different ways. The concept of the sinking fund is about paying for the cost of an asset during the life of an asset. The concept of a sinking business is about slowly drowning in debt. They are both about sinking, all right. The difference is whether the debt is being sunk or the debtor.

© 2020 Monetary Metals

Awesomely explained, once again.

Counterfeit credit = irredeemable currency = fraud = dishonesty.

You keep saying this: “What is not possible is for debtors in aggregate to reduce their debt, much less pay it off.” But I have never seen you explain why debt cannot be reduced. A person can generate income without incurring additional debt. Some of that income can be used to pay down existing debt. In aggregate, every person could do that, in which case total debt would decline.

Please explain why this is not so. Thanks.

Let me take a stab at this. Basically there are 3 kinds of debtors: individuals, corporations, and government. Even if all individuals and all corporations paid off all of their debts, the government would increase its borrowing to more than compensate. Actually capitalism is for the most part is dead in our economy. Creditism rules the roost now. The economist Richard Duncan has evidence than unless credit (the flipside of debt) increases by at least 2% per year, the economy stalls out and goes into recession or worse. This is why the Fed is so rapidly increasing its balance sheet to compensate for the lack of demand due to the pandemic and stave off an even worse depression. It is the nature of our fiat money system. This is why the interest rate must fall … to keep the debt still serviceable. Unbelievably this system can go on longer than most can imagine as long as the interest rate keeps falling. However, this system will all of a sudden end very quickly when confidence in the currency is lost. I know this is not the best explanation. Maybe someone else can chime in to correct what I got wrong and/or fill missing gaps.

Is there a reliable measure of total capital which could confirm whether the economy as a whole is undergoing net capital destruction?

Thanks for the effort, dclinde. But I still have never seen Keith’s logic on this point. There is a big difference between what will likely happen to total debt and what is logically impossible. Keith says it is not possible to reduce total debt outstanding. I understand that every paper (or electronic) dollar represents debt, but paying down bank loans reduces the number of dollars outstanding. If people were to pay down more debt than the quantity of new bank loans, the net effect should be a reduction.

As for the “total capital” question, I think you might find the Austrian Economics concept relevant. The Austrian school thinkers postulated a complex capital structure that includes all goods which exist not for direct consumption, but for the purpose of eventually enabling consumption. Some of these capital goods are very close to the point of consumption: product display shelves in retail stores, software supporting online sales, and such. Other capital goods are farther away from direct consumption: warehouses, shipping containers, for example. Other things are even further out: steel factories, iron ore mines, and so on. The only way to aggregate these myriad things is in terms of monetary value – but that ultimately depends on what entrepreneurs think market prices for countless consumer goods will be in the future. In short, it’s an impossible task to estimate “total capital” except in the most trivial and meaningless terms. At least that is my understanding of the Austrian model presented by Mises, Rothbard, Hayek, and others. But I stand ready to learn from anyone who can offer a different or more complete insight.

https://youtu.be/iFDe5kUUyT0 Here, Tom, I found it. Start watching at 12:30. Like I said, if the amount of fiat currency doesn’t keep expanding, there will be a total economic collapse. Let’s assume as you wrote that it is theoretically possible to retire all debt. And the currency is debt. Then no debt = no currency = no economy. In other words, there will be a complete economic collapse and we will be back to square one using barter. I don’t mean to be sensational, but billions of people would die as a result. Creditism can carry you a long way (and it has) but it is a fatally flawed system. It cannot go on forever. Imo, we really need to get back to using real money, i.e. gold and silver, sooner rather than later. I hope this is somewhat helpful.

Regarding the total capital question, I am not sure if it matters much on the precise definition of capital. Also once the definition is agreed upon, I am not sure if it matters much if you can put a precise monetary or currency value on total capital in any particular moment in time. I am pretty sure some really smart economists could make some good estimates. But over time in our falling interest rate fiat money system, the seed corn has to be consumed as articulated by Keith.

I certainly agree that unredeemable currency is a terrible idea. But my one narrow question remains unanswered.

“Let’s assume as you wrote that it is theoretically possible to retire all debt.” Trouble is, that is not what I wrote. Every time anyone has tried to answer my question he has gone right to the reductio ad absurdum. I accept that zero is not possible. But I wonder why the total debt couldn’t move up and down with the net amount of new borrowing? Keith says it is logically impossible for debt to decline.

As for the capital question, I think most government statistics are worthless. Any number claiming to show what is happening to the capital stock would be far worse than most. Capital consumption occurs when people fail to maintain capital assets or when they fail to adjust the capital stock to meet changing needs. To answer the question in an aggregate statistic, the data gatherer would have to make this entrepreneurial judgment about every significant capital asset in the country. Impossible, in my opinion.

OK how do we respond to someone who says there’s no capital destruction, I see buildings going up everywhere, help wanted signs everywhere (before Corona), stock market up.

Every time there is a recession we get a pretty good picture of the capital destruction which has occurred. There is no viable quantification, perhaps, but the results are visible as capital assets go idle and capital asset prices fall to very low levels.

I see a lot of people whining about capitalism. My take is capitalists are not in power. Why would capitalists support a system which destroys capital? When they were in power in the US 1865-1930 they supported the gold system. I would like to get critics of capitalism to redirect their criticism at our debt-money system, not the grocer down the street.