The Swiss Franc Will Collapse

I have worked to keep this piece readable, and as brief as possible. My grave diagnosis demands the evidence and reasoning to support it. One cannot explain the collapse of this currency with the conventional view. “They will print money to infinity,” may be popular but it’s not accurate. The coming destruction has nothing to do with the quantity of money. It is a story of what happens when interest rates fall into a black hole.

Yields Have Fallen Beyond Zero

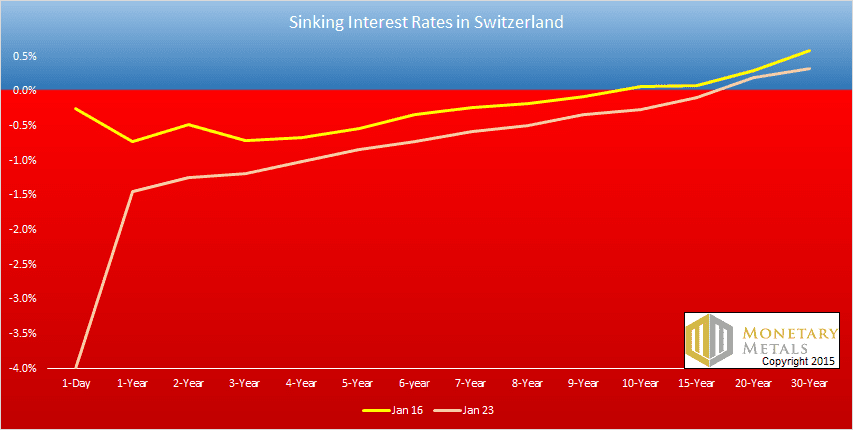

The Swiss yield curve looks like nothing so much as a sinking ship. All but the 20- and 30-year bonds are now below the water line.

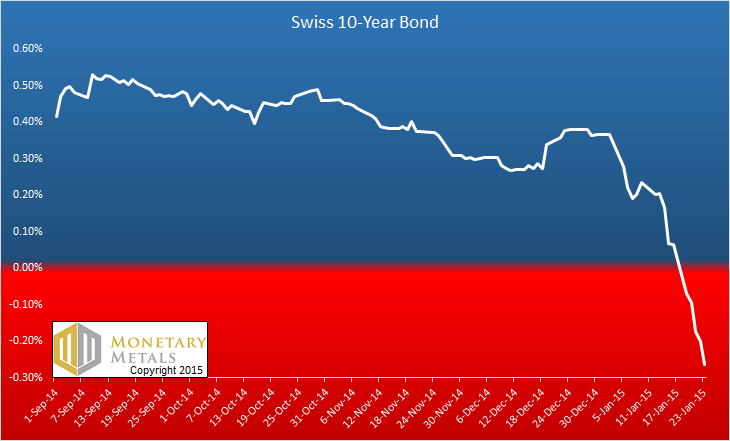

Look at how much it’s submerged in just one week. The top line (yellow) is January 16, and the one below it was taken just a week later on January 23. It’s terrifying how fast the whole interest rate structure sank. Here is a graph of the 10-year bond since September. For comparison, the 10-year Treasury bond would not fit on this chart. The US bond currently pays 1.8%.

The Swiss 10-year yield was as high as 37 basis points on Friday January 2. By the next Monday, it had plunged to 28, or -25%. By January 15—the day the Swiss National Bank (SNB) announced it was removing the peg to the euro—the yield had plunged to just 7 basis points. It has been nonstop freefall since then, currently to -26 basis points.

What can explain this epic collapse? Why is the entire Swiss bond market drowning?

Drowning is a fitting metaphor. In my dissertation, I describe several harbingers of financial and monetary collapse. The first is when the interest interest rate on the long bond goes to zero. I discuss the fact that a falling rate destroys capital, and that lower rates mean a higher burden of debt. If the long bond rate is zero then the net present value of all debt (which is effectively perpetual) is infinite. Debtors cannot carry an infinite burden. As we’ll see, any monetary system that depends on debtors servicing their debt must collapse when the rate goes to zero.

I think the franc has reached the end. With negative rates out to 15 years, and a scant 33 basis points on the 30-year, it is all over but the shouting.

Not Printing, Borrowing

Let’s take a step back for a moment, and look at how the recent chapter unfolded. It began with the SNB borrowing mass quantities of francs. Most people say printed, but it’s impossible to understand this unprecedented disaster with such an approximate understanding. It’s not printing, but borrowing.

Think of a homebuyer borrowing $100,000 to buy a house. He never gets the cash in his bank account. He signs a bunch of paperwork, and then at the end of the day he has a debt obligation to repay, plus the title to the house. The former owner has the cash.

It works the same with any central bank that wants to buy an asset. At the end of the day, the bank owns the asset, and the former owner of the asset now holds the cash. This cash is the debt of the central bank. It is on the bank’s balance sheet as a liability. The bank owes it.

This is vitally important to understand, and it can be quite counterintuitive. If one thinks of the franc (or dollar, euro, etc.) as money, and if one thinks that the central banks print money, then one will come to precisely the wrong conclusion: that there is nothing owed, and indeed there is no debtor. In this view, the holder of francs has cash, which is a current asset. End of story.

This conclusion could not be more wrong.

Certainly, the idea of the central bank repaying its debt is absurd. By law, payment is deemed made when the debtor pays in currency—i.e. francs in Switzerland. However, the franc is the very liability of the SNB that we’re discussing. How can the SNB pay off its franc liabilities using its own franc liabilities as means of payment?

It can’t. This is a contradiction in terms. Thus it’s critical to understand that there is no extinguisher of debt in the regime of irredeemable paper currency. You may get yourself out of the debt loop by paying in currency, but that merely shifts the debt. The debt does not go out of existence, because paying a debt with an IOU cannot extinguish it. Unlike you, the central bank cannot get itself out of debt.

However, it can service its debt. For example, the Federal Reserve in the U.S. pays interest on reserves. Indeed, the bank must service its debts. It would be a calamity if a payment is missed, if the central bank ever defaulted.

The central bank must also maintain its liabilities, which is what it uses to fund its assets. If the commercial banks withdraw their deposits—and they do generally have a choice—the central bank would be forced to sell its assets. That would be contrary to its policy intent, not to mention quite a shock to brittle economies.

Make no mistake, a central bank can go bankrupt. This may seem tricky to understand, as the law makes its liability legal tender for all debts public and private. A central bank is also allowed to commit acts of accounting (and leverage) that would not be tolerated in a private company. Regardless, it can present misleading financial statements, but even if the law lets it get away with that, reality will have its revenge in the end. The emperor may claim to be wearing magnificent royal robes, but he’s still naked.

If liabilities exceed assets, then a bank—even a central bank—is insolvent and the consequences will come soon enough. The cash flow from the assets will sooner or later become insufficient to pay the interest on the liabilities. No central bank wants to be in a position where it is obliged to borrow, not to purchase asset but to service a negative cash flow. That is a rapid death spiral. It must somehow push down the interest rate on its liabilities (which are typically short term) to keep the cost of financing its portfolio below the revenue generated on the assets.

This becomes increasingly tricky when two things happen. One, the yield on the asset goes negative. Thus, the even-more-negative (and even more absurd) one-day rate of -400 basis points in Switzerland. Two, the issuance of more currency drives down yields even further (described in detail, below).

Events force the hand of the central bank. It goes down a path where it has fewer and fewer choices. That brings us back to negative interest rates out to the 15-year bond so far.

The Visible Hand of the Swiss National Bank

So the SNB issued francs to fund its purchase of euros. Next, it spent the euros on whatever Eurozone assets it wished to buy, such as German bunds.

It’s well known that the SNB put on a lot of this trade to keep the franc down to €0.83 (the inverse of keeping the euro down to CHF1.2) l. It also helped push down interest rates in Europe. The SNB was a relentless buyer of European bonds.

That leads to the question of what it did in Switzerland. The SNB was trading new francs for euros. That means the former owner of those euros then owned francs. These francs have to stay in the franc-denominated domain. What asset will this new franc owner buy?

I frame the question this way deliberately. If you have a 100-franc note, you can put it in your pocket. If you have CHF100,000, you can deposit it in a bank. If you have CHF100,000,000 (or billions) then you are going to buy a bond or other asset (depositing cash in a bank just pushes it to the bank, who buys the asset).

The seller of the asset is selling on an uptick. He gives up the bond, because at its higher price (and hence lower yield) he now finds another asset more attractive on a risk-adjusted basis. Risk includes his own liquidity risk (which of course rises as his leverage increases).

As the SNB (and many others) relentlessly push up the bond price, and hence push down the yield, the sellers of the ever-lower yielding bonds have fresh new franc cash balances.

The Quantity Theory of Money holds that the demand for money falls as the quantity rises. If demand for money falls, then by this definition the prices of all other things—including consumer goods—rises. It is commonly held that people tradeoff between saving money vs. spending money (i.e. consumption). The prediction is rising consumer prices.

I emphatically disagree. A wealthy investor does unload his assets to go on an extra vacation if he doesn’t like the bond yield. A bank with a trillion dollar balance sheet does not dole out bigger salaries if its margins are compressed.

So what does trade off with government bonds? If an investor doesn’t want to own a government bond, what else might he want to own? He buys corporate bonds, stocks, or rental real estate, thus pushing up their prices and yields down.

And then, in a dysfunctional monetary system, you can add antique cars, paintings, a second and third home, etc. These things serve as surrogates for investment. When investing cannot produce an adequate yield, people turn to non-yielding non-investment assets.

The addition of a new franc at the margin perturbs the previous equilibrium of risk-adjusted yields across all asset classes. Every time the bond price goes up, every owner of every franc-denominated asset must recalculate his preferences.

The problem is that the SNB does not create any more productive investment opportunities when it spills more francs into the Swiss financial system. Those new francs have to chase after the existing assets.

Yields are falling. They necessarily had to fall.

An Increasing Money Supply and Decreasing Interest Rate

The above discussion describes the picture in every developed economy. Interest rates have been falling for 34 years in the U.S., for example.

In a free market, the expansion of credit would be driven by a market spread: available yield – cost of borrowing. If that spread is too small (or negative) there will be no more borrowing to buy assets. If it gets wider, then banks can spring into action.

However, central banks distort this. Instead of the cost of borrowing being a market-determined price, it is fixed by the central bank. This perverts the business model of a bank into what is euphemistically known as maturity transformation—borrowing short to lend long. It’s not possible for a bank to borrow money from depositors with 5-year time deposit accounts in order to buy 5-year bonds. The bank has to borrow a shorter duration and buy a longer, in order to make a reasonable profit margin.

If the central bank sets the borrowing cost lower and lower, then the banks can bid up the price of government bonds higher and higher (which causes a lower and lower yield on the long bond). This is not capitalism at all, but a centrally planned kabuki theater. All of the rules are set by a non-market actor, who can change them for political expediency.

The net result is issuance of credit far beyond what could ever happen in a free market. This problem is compounded by the fact that the central bank cannot control what assets get bought when it buys bonds. It hands the cash over to the former bond holders. It’s trying to accomplish something—such as keeping the franc down in the case of the SNB, or preventing bankruptcies, in the case of the Fed—and it has no choice but to keep flooding the market until it achieves its goal. In the US, the rising tide eventually lifted all ships, even the leaky old tubs. The result is a steeper credit gradient, and the bank can eventually force liquidity out to its target debtors.

The situation in Switzerland makes the Fed’s problems look small by comparison. Unlike the Fed, which had a relatively well-defined goal, the SNB put itself at the mercy of the currency market. It had no particular goal, and therefore no particular budget or cost. The SNB was fighting to hold a line against the world. While it kept the franc peg, the SNB put pressure on both Swiss and European interest rates.

Something changed with the start of the year. We can understand it in light of the arbitrage between the Swiss bond, and other Swiss assets. The risk-adjusted rate of return on other assets always has to be greater than that of the Swiss government bond (except perhaps at the peak of a bubble). Otherwise why would anyone own the higher-risk and lower-yield asset?

Therefore, there are three possible causes for the utter collapse in interest rates in Switzerland beginning 10 days prior to the abandonment of the peg:

1. the rate of return of other assets has been leading the drop in yields

2. buying pressure on the franc obliged the SNB to borrow more francs into existence, fueling more bond buying

3. the risk of other assets has been rising (including liquidity risk to their leveraged owners)

#1 is doubtful. It’s surely the other way around. It’s not falling yields on real estate driving falling yields on bonds. Bond holders are induced to part with their bonds on a SNB-subsidized uptick. Then they use the proceeds to buy something else, and drive its yield down.

One fact supports conclusion #2. Something forced the SNB to remove the peg. Buying pressure is the only thing that makes any sense. The SNB hit its stop-loss.

The rate of interest continued to fall even after the SNB abandoned its peg. Why? Reason #3, rising risks. Think of a bank which borrowed in Swiss francs to buy Eurozone assets. This trade seemed safe with the franc pegged to the euro. When the peg was lifted, suddenly the firm was faced with a staggering loss incurred in a very short time.

The overreaction of the franc in the minutes following the SNB’s policy change had to be the urgent closing of Eurozone positions by many of these players. The franc went from €0.83 to €1.15 in 10 minutes, before settling down near €0.96. For those balance sheets denominated in francs, this looked like the euro moved from CHF1.20 to CHF0.87, a loss of 28%. What would you do, if your positions instantly lost so much? Most people would try to close their positions.

Closing means selling Eurozone assets to get francs. Then you need to buy a franc-denominated asset, such as the Swiss government bond. That clearly happened big-time, as we see in the incredible drop in the interest rate in Switzerland. Francs which had formerly been used to fund Eurozone assets must now be used to fund assets exclusively in the much-smaller Swiss realm.

In other words, a great deal of franc credit was used to finance Eurozone assets. This is a big world, and hence the franc carry trade didn’t dominate it. When those francs had to go home and finance Swiss assets only, it capsized the market.

And the entire yield curve is now sinking into a sea of negative rates.

The Consequences of Falling Interest

Meanwhile, unnaturally low interest is offering perverse incentives to corporations who can issue franc-denominated liabilities. They are being forced-fed with credit, like ducks being fatted for foie gras. This surely must be fueling all manner of malinvestment, including overbuilding of unnecessary capacity. The hurdle to build a business case has never been lower, because the cost of borrowing has never been lower. The consequence is to push down the rate of profit, as competitors expand production to chase smaller returns. All thanks to ever-cheaper credit.

Artificially low interest in Switzerland is causing rising risk and, at the same time, falling returns.

The Swiss situation is truly amazing. One has to go out to 20 years to see a positive number for yield—if one can call 21 basis points much of a yield.

It’s not only pathological, but terminal. This is the end.

In Switzerland, there is hardly any incentive remaining to do the right things, such as save and invest for the long term. However, there’s no lack of perverse incentives to borrow more and speculate on asset prices detaching even further from reality.

Speculation is in its own class of perversity. Speculation is a process that converts one man’s capital into another man’s income. The owner of capital, as I noted earlier, does not want to squander it. The recipient of income, on the other hand, is happy to spend some of it.

We should think of a falling interest rate (i.e. rising bond market and hence rising asset markets) as sucking the juice (capital) out of the system. While the juice is flowing, asset owners can spend, and lots of people are employed (especially in the service sector).

For example, picture a homeowner in a housing bubble. Every year, the market price of his house is up 20%. Many homeowners might consider borrowing money against their houses. They spend this money freely. Suppose a house goes up in price from $100,000 to $1,000,000 in a little over a decade. Unfortunately, the debt owed on the house goes up proportionally.

With financial assets, they typically change hands many times on the way up. In each case, the sellers may spend some of their gains. Certainly, the brokers, advisors, custodians, and other professionals all get a cut—and the tax man too. At the end of the day, you have higher prices but not higher equity. In other words, the capital ratio in the market collapses.

To understand the devastating significance of this, consider two business owners. Both have small print shops. Both have $1,000,000 worth of presses, cutters, binding machines, etc. One owns everything outright; he paid cash when he bought it. The other used every penny of financing he could get, and has a monthly payment of about $18,000. Both shops have the same cost of doing business, say $6,000. If sales revenues are $27,000 then both owners may feel they are doing well. What happens if revenues drop by $3,500? The all-equity owner is fine. He can reduce the dividend a bit. The leveraged owner is forced to default. The more your leverage, the more vulnerable you are to a drop in revenues or asset values.

Falling interest, and its attendant rising asset prices, juices up the economy. People feel richer (especially if their estimation of their wealth is portfolio value divided by consumer prices) and spend freely. Unfortunately, it becomes harder and harder to extract smaller and smaller drops of juice. The marginal productivity of debt falls.

Think about it from the other side, the borrower. The very capacity to pay interest has been falling for decades. A declining rate of profit goes hand-in-hand with a falling rate of interest. Lower profit is both caused by lower interest, and also the cause of it. A business with less profit is less able to pay interest expense. Who could afford to pay rates that were considered to be normal just a few decades ago? It is capital that makes profit, and hence capacity to pay interest, possible. And it is capital that’s eroded by falling rates.

The stream of endless bubbles is just the flip side of the endless consumption of capital. Except, there is an end. There is no way of avoiding it now, for Switzerland.

How About Just Shrinking the Money Supply?

Monetarists often tell us that the central bank can shrink the money supply as well as grow it, and the reason why it’s never happened is, well… the wrong people were in charge.

I disagree.

To see why, let’s look at the mechanism for how a central bank expands the money supply. It issues cash to an asset owner, and the asset changes hands. Now the bank owns the asset and the seller owns the cash (which he will promptly use to buy the next best asset). A relentlessly rising bond price is lots of fun. It’s called a bull market, and everyone is making profits as they reckon them (actually consuming capital, as we said above).

How would a contraction of the money supply work? It seems simple, at first. The central bank just sells an asset and gets back the cash. The cash is actually its own liability, so it can just retire it. And voila. The money supply shrinks.

Not so fast.

There is an old saying among traders. Markets take the escalator up, but the elevator down. Central bank buying slowly but relentlessly bid up the price of bonds. Tick by tick, the bank forced it up. What would central bank selling do? What would even a rumor of massive central bank selling do?

Bond prices would fall sharply.

The problem is that few can tolerate falling bond prices, because everyone is leveraged. Think about what it means for everyone to borrow and buy assets, for sellers to consume some profits and reinvest the proceeds into other assets. There is increasingly scant capital base supporting an increasingly inflated—as in puffed-up with air, without much substance—asset market. A small decline in prices across all asset classes would wipe out the financial system.

Market participants have to be leveraged. Dirt cheap credit not only makes leverage possible, but also necessary. How else to keep the doors open, without using leverage? Spreads are too thin to support anyone, unlevered.

Banks are also maturity mismatched, borrowing short to lend long. The consequences of a rate hike will be devastating, crushing banks on both sides of the balance sheet. On the liabilities side, the cost of funding rises with each uptick in the interest rate. On the asset side, long bonds fall in value at the same time. If short-term rates rise enough, banks will have a negative cash flow.

For example, imagine owning a 10-year bond that pays 250 basis points. To finance it, you borrow at 25 basis points. Well, now imagine your financing cost rises to 400 basis points. For every dollar worth of bonds you own, you lose 1.5 cents per year. This problem can also afflict the central bank itself.

You have a cash flow problem. You are also bust.

The Bottom Line

The problem of falling rates is crushing everyone, but raising the rate cannot fix the problem. It should not be surprising that, after decades of capital destruction—caused by falling rates—the ruins of a once-great accumulation of wealth cannot be repaired by raising the interest rate.

I do not see any way out for the Swiss National Bank and the franc, within the system of irredeemable paper money. However, unless the SNB can get out of this jam, the franc is doomed. I can’t predict the timing, but I believe the fuse is lit and the powder keg could go off at any time.

One day, a bankruptcy will happen. Soothing voices will assure us it was unexpected. Then another will happen, perhaps triggered by the first or perhaps not. Then the cascading begins. One party’s liabilities are another’s assets. ABC’s bankruptcy wipes out DEF’s asset. Since DEF is leveraged, it cannot absorb much loss until it, too, is dragged under.

Somewhere in the midst of this, people will turn against the franc. Today, it’s arguably the most loved paper currency. However, I don’t think it will take too many capital losses in Switzerland, before there is a selling stampede. The currency will fall to zero, in a repeat of a pattern that the world has seen many times before.

People will call it hyperinflation (I don’t prefer that term). Call it what you will, it will be the death of the franc. It will have nothing to do with the quantity of money.

Two factors can delay the inevitable. One, the SNB may unwind its euro position. As this will involve selling euros to buy francs, the result will be to put a firm bid under the franc. Two, speculators will of course know this is happening and eagerly front-run the SNB. After all, the SNB is not an arbitrager buying when it can make a spread. It is a buyer by mandate (in this scenario) and must pay the ask price. Even if the SNB does not unwind, speculators may buy the franc and wait for it to happen. And of course, they could also buy based on a poor understanding of what’s happening, or due to other perverse incentives in their own countries.

Bankruptcies aside, the franc is already set on a hair-trigger. Something else could trip it and begin the process of collapse. There is little reason for holding Swiss francs in preference to dollars. The interest rate differential is huge. The 10-year US Treasury pays 1.8%. Compare that to the Swiss bond which charges you 26 basis points, and the difference is over 208 points in favor of the US Treasury. Once the risk of a rising franc is taken out of the market (by time or price action) this trade will commence. A falling franc against the dollar will add further kick to this trade. A trickle could become a torrent very quickly.

I would not be surprised if the process of collapse of the franc began next week, nor if it lingered all year. This kind of event is not susceptible to a precise prediction of when.

What is clear is that, once the process begins in earnest, it will be explosive, highly non-linear, and over quickly (I would guess a matter weeks).

I plan to publish a separate paper revisiting my Gold Bonds to Avert Financial Armageddon thesis in light of the Swiss crisis. I will save for that paper my assessment of whether or how gold bonds can provide a way out for the Swiss people trapped in the terminal phase of irredeemable paper money.

Keith..man you are way out there.!!!

Love your articles and they are top of my reading list when they arrive..

Any chance you can darken the type, its so difficult to read ??

Yes, this looks like a brilliantly frank article.

I increased the font size, read it a few times and thought about it for a couple of days to let it sink in.

This is my supportive comment: Money needs to function as a store of value, not a hot potato.

They could always sell Euros and buy gold. Oh yeah, I forgot, they voted against increasing their gold reserves !

They did not vote against buying gold.

They voted against holding a minimum percentage of assets in gold AND not selling it ever.

The SNB has the flexibility to buy AND sell gold.

In effect, they will only sell/lease, they will never buy a single gram except if a new monetary world order emerges.

By the way, great article !

I find myself having to argue against the article. I only have about 30 minutes, so it will be a bit short and sharp.

– A negative Yield to Maturity indicates that the CHF is currently considered a safe haven and that large investors are prepared to pay a premium to hold them. The bonds are not actually charging holders interest. And indeed, any foreign owner has now made substantial currency gains in the last two weeks. A negative YTM does not mean the Swiss are in the dung heap.

– The statement “If the long bond rate is zero then the net present value of all debt (which is effectively perpetual) is infinite” is a fallacy. If the long term rate is zero, then the NPV = Face Value of the bond.

– I now have to jump over the other fallacies, as they follow on from the previous fallacy. For example,

“Debtors cannot carry an infinite burden. As we’ll see, any monetary system that depends on debtors servicing their debt must collapse when the rate goes to zero”.

There is no infinite burden. The debtor, or bond issuer, only has to pay the bond interest and the FV at maturity.

– “Certainly, the idea of the central bank repaying its debt is absurd. By law, payment is deemed made when the debtor pays in currency—i.e. francs in Switzerland. However, the franc is the very liability of the SNB that we’re discussing. How can the SNB pay off its franc liabilities using its own franc liabilities as means of payment?”

In the same way that the Fed or the BoE only promises to pay a USD on a USD, or a GBP on a GBP. Since we moved off the gold standard that is the way the banking system works. Nothing to consider, really.

-” If the commercial banks withdraw their deposits—and they do generally have a choice—the central bank would be forced to sell its assets”.

Oh come on, where on earth can a commercial bank move its reserves at the central bank to? It is an IMPOSSIBLE accounting function unless it asked for paper cash. Which is hardly likely, substituting tonnes of decaying paper for a nice number at the Central Bank.

Central Banks cannot go insolvent, they will simply carry the losses as a negative accounting number forever.

Even banks can remain insolvent for decades provided that they have liquidity provided by the Central Bank. Just go and check on the Japanese lot.

Running out of time here.

Another fallacy “depositing cash in a bank just pushes it to the bank, who buys the asset” NO, the commercial bank will normally leave the deposit it at the Central Bank as reserves. Check out how the increase of reserves at the BoE, Fed, SNB EXACTLY match the amount of QE.

There was a lot more to comment on, and I agree that the result is that asset prices get pumped up.

But there is no reason to think that the CHF will collapse overnight. The SNB would probably be happy to see a decline in value, but they still have an interest rate lever, a load of forex assets to keep things steady and above all a functioning economy with a current account surplus and some 6,000,000 hard working, conscientious Swiss producing quality world beating products.

“The statement “If the long bond rate is zero then the net present value of all debt (which is effectively perpetual) is infinite” is a fallacy. If the long term rate is zero, then the NPV = Face Value of the bond.”

Keyword here is “perpetual”. A perpetuity bond discounted at 0% will have an infinite NPV.

Yep, but the above was not talking about perpetuity bonds, and are there any left in existence?

There are still perpetual war bonds in the uk but that is not what keith is talking about. In a fiat currency system the debt cannot be extinguished. From the point of view of the issuer the debt cease to exist but that is not true system wise since the proceed will eventually be deposited at a bank and thus be used either to generate new credit or as reserve at the central bank. From the point of view of the system the debt as merely been transferred. At least that is what I gathered from keith’s previous article.

Hi,

– “In a fiat currency system the debt cannot be extinguished”

On an individual basis debts are repaid, however collectively I agree, if all the debts were cancelled there would be no money left and the world would grind to a halt.

Generally people will not borrow to fund buying bonds, as the interest paid on the loan would be greater than the interest gained.

Bond purchases.

If both the bond issuer and the buyer have an account at the same bank, then all that happens is that the deposit is transferred from one account to the other. The bank’s balance sheet does not change, no extra reserves are created.

Note that banks do NOT lend out deposits. This is an often misunderstood concept about banking. Every time a bank makes a loan it issues new money.

Its balance sheet is expanded on both sides, no reserves are used and no other deposit accounts are required.

However, if a CB enters the market and buys bonds, this results in a one-to-one increase in reserves at the CB. The proceeds of the bond sale are paid into a deposit account, which is the bank’s liability, and the same amount is entered as a bank’s asset, and drops into the reserve account at the CB.

Keith,

That is a brilliant piece, congratulations and thank you!

Thanks for the comments, everyone!

Bastiat: thanks for your explanation. I would add one thing to respond to Windman. Suppose Acme Inc sells a bond at 4% yield. And then the prevailing rate in the market falls to zero. Acme continues to pay 4%. The sum of the payments is not the face value, much less the net present value of that payment stream.

Hi,

Once the bond has been issued the issuer is not affected by the market price of the bond. He pays the 4% on the FV of the bond in perpetuity or until the bond has reached maturity, at which time he repays the FV.

The price of the bond will clearly be calculated based on prevailing interest rates, the date of maturity and market assessment of risk. But the issuer does not care about this and is not affected by it. The business decision was to raise long term finance at a certain level of interest, which is expected to be attained by future revenues.

Markets determine the price of tradeable bonds. Above you indicate that somehow the SNB will take a huge hit as bonds could reach astronomical levels. This will not happen as the market prices risk into the equation.

And ACME will continue to pay 4% on the capital raised by the bonds, whilst the bond holders will have to handle market fluctuations based on interest rates.

Windman: You may disagree, but I am saying that the NPV of the bond must be calculated–not at the original rate of interest when the bond was sold–but at the current market rate of interest. In other words, the NPV rises when the market interest rate falls.

I have written a lot on this subject. I am pretty sure I linked one of my articles in this paper. If not, let me know and I will post a link.

Agreed.

I am not arguing that the NPV does not reflect the prevailing interest rate. That is clearly the way that the bonds are priced in the market.

I am saying that the liability of the bond issuer does not increase with the market value. So even if the interest rates sink to zero and the bond price shoots up, there will be no change on the balance sheet of the bond issuer.

Windman, what you say about liability is true enough, and GAAP may not require a mark-to-market treatment in every balance sheet. But that isn’t what the NPV calculation is about.

NPV is the way to factor time and risk differences out of a calculation of fundamental value. As soon as a company issues a bond and is holding its then-NPV in cash, we are at the zero-risk origin. They could instantly extinguish the debt. Then they start using the money (hopefully in a productive way, but) inevitably also risking it. Midway through that business strategy you are asked to appraise the company, perhaps to determine their creditworthiness. The valuation you’ll want for that debt is NPV, even if the company hasn’t booked it at market. That is what it would cost you today to replicate this plan at this half-complete stage. It is what you’d realize if you bought the company and scuttled all its plans and sold off all assets. Sure those are extreme situations, but they represent level playing fields where you can start to compare business A with business B.

I just read the first part of this, and I think IT ROCKS! It’s an excellent explanation of how the current banker monopoly money is indeed a debt based money system. Regardless of the intentions of how it got started down this path, it is what it is now, a debt-based system of money, which doesn’t work! It may work for those that have a huge amount of debt on their balance sheet, and therefore try and purport that debt is wealth, but it doesn’t work for me. I do not believe that debt is wealth and never will.

I feel I will be able to better explain how our current system is without question, a debt-based system after having read just the first part! Hopefully I will be able to finish reading the entire thing this evening. Off to work for now.

A Big Thank you to Keith Weiner!

The money system has always been debt based.

I cannot envisage a alternative system that would work. Maybe you could propose one?

Actually money doesn’t require debt since it started as simply a medium of exchange. Similarly debt can exist without money for instance in a barter economy. The monetary system wasn’t debt based before 1971. However it is tempting to ask for abolishing the very concept of debt but for all it’s ill consequences debt does have an essential role to play and could not be abolished without the cure being worse than the disease.

Hi,

A debt based money system goes way way further back.

Here’s a potted history.

http://www.xat.org/xat/moneyhistory.html

You are referring to the end of the gold era. There was never enough gold to back the currencies, ever. It was all trust in IOU (some non-existent gold).

The world is run on debt and always has been.

Windman,

Gold is money. But it does not have to be the “currency” for indirect exchanges. When paper instruments entered the scene, they were at first, not DEBT instruments (indeed usury laws prohibited this); they were CLEARING instruments. Yes, there is a component of trust and a sort of IOU involved, but there is also (usu)tangible goods being cleared and well-trod marketplace routes to carry the goods and monies, so the “trust” involved had a wholly different character and related to patterns of consumption, not of long term saving or investment.

The world may indeed need to run a “debt” because at the very least we will mostly all be here next year, still needing to survive. The debt that puts us in is something no one minds being monetized. It will be extinguished as we finally do survive by producing enough to pay our bills.

But the debt Keith describes is not merely monetizing some larger certainty such as the immutability of the gold stock, or the survival of the species. It is irredeemable debt for its own sake, backed by the force of a Legal Tender Law and a tax on gold transactions. These artificial and coercive additions to the natural order call the whole enterprise of modern currency into doubt. Keith is solidifying those doubts.

Keith’ presentation is fascinating. Thanks for the great piece.

Windman’s arguments should be carefully considered & studied – often trivial logical errors can lead to terribly false conclusions. I will monitor this debate with great interest.

There is a 4h possible explanation for the drop in interest rates 10 days before: if anyone had heard rumors about dropping the peg, they could have decided to front-run the event by buying CHF in huge quantities beforehand, in view of making a quick forex profit. Surely the SNB did not decide 10 minutes before and without consulting at least a few people. 10 days does feel plausible. And any of the people consulted would typically know how to access leveraged money to buy CHF with e.g. EUR, to make a quick buck. It is then the logical conclusion to place those CHF into bonds until it’s time to pull out. It is very similar to point #2, but with the evil twist of deliberate front-running the event, rather than external economic considerations.

Finally, if Keith is 100% right, and if I understand correctly, then it means there exists a catastrophic state in the “macro monetary system” that has never been envisaged by monetary theorists and/or Central Banks (to my limited amateur knowledge).

This oddly resembles an unforeseen Nash equilibrium in a complex system, which is not normally reached (never happened before) unless a sudden & drastic external condition (De-pegging) causes the system to fall into this particular state – and it can’t exit from it naturally (equilibrium / attractor). I would be delighted if someone could reproduce Keith’s arguments above in Game Theory presentation, to determine if there indeed such state?

Windman’s objections need to be examined first, obviously.

Virgule: I agree speculators always have ways of finding out what the bureaucrats will do and front-run them, That would explain upward pressure on CHF, but how does it explain upward pressure on Swiss bond prices / downward pressure on Swiss rates?

As to equilibrium, well right now who would risk a spike in CHF, by shorting it? Especially with everyone knowing that CHF is a “good” currency, and everyone knowing the SNB could unwind its euro trade. However, sooner or later…

George Soros was some how able to move be for most.not sure what he did, but his loss was minimal. Some one with more understanding of the matter may like to look in to it (How The Swiss National Bank Almost Crushed George Soros)

Thank you Keith

I am new to all this,you explain with more clarity then most, under standing the mechanics of the financials helps me to comprehend a little more.

I have seen no indication that the intention to lift the peg was disclosed outside of the SNB.

Although it has been speculated about for some time that the peg would be relaxed sometime this year.

Christine Lagarde stated on an interview that she was not informed beforehand about the intentions of the SNB.

Keith,

Agree bankruptcy will happen eventually, but don’t the Swiss have time even in case of rising rates for a year or two? The debt to GDP is 40% if I’m not mistaken, and their annual budget is under control. Couldn’t they reverse course in a year or two and really start levering up their balance sheet. Japan is at 260% and still operating. What am I missing ?

Thnks as always,

Andrew

Why do you agree that the SNB will become insolvent?

It cannot happen, the SNB could run an insolvent balance sheet for ever, and will never have any liquidity issues, it is the ultimate source of CHF liquidity.

A Central Bank cannot default as long as it’s liabilities are legal tender. Effectively it’s liabilities are infinite and act as money. What’s interesting in this article is the issue of final settlement. It is true that in our global fiat system there is no final settlement but the question remains how important is this and if all the participants are happy to exchange each others IOUs what’s to prevent such a system from functioning successfully. One of the commentators refers to 6,000,000 hard working Swiss and indeed that is the eventual backing of the SNB’s liabilities but the question remains are those hardworking Swiss entirely happy to effectively back an infinite stream of IOUs? My personal guess is the Japanese will be the first to answer that all important question

Keith, I still cannot get my head around a central bank getting into financial difficulty since it usually holds bonds until maturity any paper loss will never materialise unless the sovereign defaults.

Winning!

As an aside, almost no one on ZH understands a word of your articles and they are therefore grumpy and angry when they comment but your blog gets great, thoughtful comments even in disagreement, and more of them now if I’m not mistaken.

Your success could help us all Keith. Thank you!

The “basis school” might have a fatal flaw which is continuously dismissed any eastern political influence and its potential impacts.

They believe in “dismal monetary science” which is great in theory but not performing as well in the real world.

Swiss franc even rotten will survive longer than most of other fiat and will still be here at the end of 2015…

Brilliant piece Keith; you really bring it all together in this one. Belongs in a time capsule somewhere. Maybe in Bill Gates’ seed bank serving as an explanation for future generations for what these policies can do.

One thing. You say persistently falling rates cause “capital destruction.” If “capital” is anything, it is wealth. If “wealth” is anything, it is (stored) energy. According to the Law of Conservation of Energy, energy is never destroyed but transferred from one form to another. Therefore wealth (capital) is never destroyed but transferred. So capital is not being destroyed per se, but being transferred up the pyramid. Agree?

There is no relationship between wealth and energy. None at all. To draw a parallel only causes confusion and misunderstanding.

For example I can plant a bomb under a Ferrari. This will convert a minuscule amount of material into energy but destroy a fair chunk of wealth.

You are thinking too literally. Money is abstract. As our time, labor and resources is represented by money, energy is the only objective scientific definition of wealth.

The sun transfers energy into plants. We convert that energy into the product of our labor and exchange it for someone else’s energy. Commerce is just bartering energy. Money is the proxy. Money must serve the purpose of storing this energy. But of course it doesn’t because it is controlled by the banks who through inflation and deflation use it as a mechanism of wealth transfer.

You making the same mistake Ricardo did when he tried to measure value in units of labor except you are using units of energy. If you use a lot of energy producing something nobody wants is the value of the energy spent “stored” in that useless item? Similarly if an item can be produced in a more energy efficient way does it become less valuable than the one produced with more energy?

My point is how money interacts with “wealth” and how it is used to transfer that wealth, which must be defined in the most objective way. Your example wouldn’t apply because there would be no market price for such waste. Yes, energy exists outside of commerce.

You have moved the goalposts, but in any case this argument is not going anywhere, as the claim

“energy is the only objective scientific definition of wealth”

is false. The concept of wealth itself is context dependent. As a simple example, a man with a water source in a drought would be very wealthy, but in a six month monsoon would have no income and be poor. And it is difficult to see where the amount of energy expended is relevant.

The only way of measuring material wealth is to base it on the market value of his possessions and skills.

You will understand what I mean when your currency crashes. Your wealth will not have been “destroyed.” It will have been transferred up the pyramid to the bankers. The result of persistently declining interest rates, which was the original context.

Another thought provoking article. It is refreshing and instructive to look at things with a fresh pair of eyes. Keep up the good work, Keith. Well done!

Some follow up questions:

1.

Would you consider this mechanism, or let’s call it ‘sequence of steps and events,’ to be the typical way in which make believe currencies make their way to the graveyard? Critically, is the so-named “hyperinflation” of currencies signalled/caused/preceded by a seemingly unstoppable fall in interest rates into the black hole? Did, for example, the Zimbabwe Dollar hyperinflate this way?

2.

Conversely, should we see rising interest rates, such as in the case of the Rouble, as a healthy sign for that currency? Or, this is also, but for different reasons, a bad sign?

3.

Would it not make sense for the SNB, and CBs in general, to buy up as much real money as they can get their hands on before their baby turns into dust. Indeed, could they save it in this way, by backing it with gold? Would that arrest its slide into the abyss?

Thanks.

1. Hyperinflation is caused by a total loss of faith in the currency, not by interest rates.

2. Putin raised the interest rates dramatically to prevent further slides of the Rouble. The Russians are teetering a little on the edge.

3. We will not see a return to the gold standard and the CHF is not about to collapse, the Swiss have a well deserved unshakable faith in their currency, country, political system and themselves.

-“This perverts the business model of a bank into what is euphemistically known as maturity transformation—borrowing short to lend long. It’s not possible for a bank to borrow money from depositors with 5-year time deposit accounts in order to buy 5-year bonds. The bank has to borrow a shorter duration and buy a longer, in order to make a reasonable profit margin.”

That IS the banking model, they lend long and borrow short. This gives them a liquidity risk, but that is nowadays always fixed by the CB.

Banks do not hold substantial numbers of bonds. Their assets are mostly loans to companies and individuals. In order to reduce the volatility of their balance sheets, they may offer higher interest rates for long term deposits, particularly if they expect interest rates to rise.

“SNB put itself at the mercy of the currency market. It had no particular goal, and therefore no particular budget or cost”

I would argue that the SNB has the most clearly defined goal of any central bank. To sell enough CHF against EUR, USD, GBP, CAD and a few others in order to peg the CHF at EUR 1.20.

On the other hand I have no idea what Draghi is trying to do, that is just a huge mess.

I am broadly in agreement with the effect on asset prices, this has become a large problem.

However, I am unsure why you decided to single out Switzerland. The US, the UK and Europe have even worse problems, at least the Swiss have a functioning economy. People will continue to hold the CHF as it has exhibited very long term stability. The USD has a huge advantage in being the world’s reserve currency, but the GBP is not stable, they regularly have a GBP crisis, and the EUR is simply not intrinsically stable.

The commercial banks are at risk from property prices and company defaults, but not generally from stock market or bonds.

The investment banks running proprietary trading are vulnerable, but the area where the SHTF is the shadow banking sector, all those pension and insurance companies, trading companies and dealers, where liquidity is loaned against assets. When those assets collapse, then so does all the liquidity, and it is Hello 2007, nice to see you again.

Keith is right, without drastic action which so far the CBs are dead set against, the CHF will be destroyed, but it will be the Swiss economy that goes first, taking the CHF with it.

Don’t believe me? Rising asset prices and declining yields reflect the difficulty of getting a return – on anything. This shows up in the real economy and is currently a worldwide phenomenon, witness falling commodities, energy as obvious symptoms. For sure, paper financial assets appear to be rising measured in paper money but this is an illusion and will disappear the moment faith in paper is lost because the paper money does not track the real economy. That’s when you get “hyperinflation.”

At present, real assets are becoming less and less productive, nobody can invest and get a satisfactory return – only malinvestments can get made, think government schemes, but these are illusions also, there is still no return.

In Switzerland, the real economy is about to get another hammering, one obvious sign is the overnight 20% loss of export competitiveness when the CHF jumped but this is just a symptom of the return on assets malaise.

The only way out is for asset prices to fall and thus become productive again. Coming soon to an economy near you whether you like it or not.

-“without drastic action which so far the CBs are dead set against”

So a few trillion in the States, a trillion in Europe, lost count in Japan, half a trillion in the UK, interest rates at zero is NOT drastic action? Jeeze, what would you define as drastic?

But you start off against the CHF and then go straight into the rest of the world which has even worse problems, but somehow the Swiss and the CHF are in your opinion by far in the worst position?

Swiss exports are among the highest quality you can find on the globe. From watches to industrial machinery, “Swiss Made” is a recognizable brand, and sells at a premium. If the watches go up in price, then the Asians will buy even more due to the extra “status”. Knowing that reliable, modern technology sells, the Swiss invest large amounts in staying at the forefront.

With no natural resources the Swiss also have to import all energy and raw materials. These have now become 20% cheaper.

I have somehow become the defender of Switzerland. It was not intentional, but to see where far greater problems exist you really have to look at other economies.

For example the UK, which has been running a current account deficit for decades, appears to survive on selling inferior inflated property to each other and arrogance.

We are talking about Switzerland on this thread, no? I do not diasagree that the RoW is worse. The CBs have certainly taken drastic action of exactly the wrong kind. They are propping paper assets up – exactly what the banks want but a disaster for the real economy, which is my point.

On the subject of NPV of a bond at zero rate, Keith is correct. Given a zero discount rate, the value of future cashflows, interest and principal, is simply the sum of all the future cashflows, with no discount for time value. If the cashflows never end, the sum is infinite. However, nothing in this world is infinite, all promises that do not have a term limit are broken.

The assertion that banks will suffer negative cashflows if short term rates rise enough, is not true. Most banks lend money at floating rates. Credit card debt and commercial lending is done this way, linked to ST rates. A competent bank will pay attention to duration mismatch. They try to match the duration of assets with that of funding. Deposit funding is also short term duration. So when rates rise, both the interest income and interest expense of a bank will rise. All banks will make bets on the direction, so some will skew more towards longer duration loans and securities, others will shorten the duration of their assets. It is a dynamic process, not fixed.

Mortgage REITs play the game of borrowing in the repo market and buying 15yr and 30yr mortgages, but they offset much of the duration mismatch with lots of hedging with swaps and swaptions. Some financial institutions will suffer losses with big interest rate moves, but who and how much is not easy to generalize.

Keith’s analysis of Swiss negative interest rates is a fantastic contribution. I wish it could be revised and corrected where there are mistakes because this is history, a very big deal in my opinion. Understanding what is happening now could is crucial to our wellbeing.

Windman,

“Note that banks do NOT lend out deposits. This is an often misunderstood concept about banking. Every time a bank makes a loan it issues new money.

Its balance sheet is expanded on both sides, no reserves are used and no other deposit accounts are required.”

This contradicts what is being taught by textbooks and universities. Also if what you say is true then what happens when the borrower withdraw the money? The liability of the bank shrinks but surely it will not reduce the size of the loan on the asset side to match it. Therefore the reduction must come out of the total deposits. Furthermore if deposits weren’t used to make new loans then why would banks compete for them and often pay interest on them in a normal environment?

Text books and universities still go on about fractional reserve banking, loaning out deposits and all that nonsense. It is all rubbish. Forget it if you want to understand how banks work.

From your question, when the customer takes out a loan he has a liability to pay back (which is the bank’s asset) and a deposit in his account to use.

Cash withdrawal.

Customer withdraws 5 USD paper at a counter. His deposit account is marked down 5 USD electronically, and the bank takes 5 USD paper from its vault cash, marking down its assets accordingly. (The bank’s balance sheet has been reduced by 5 USD)

Electronic transfer to account within same bank.

Customer tells bank to transfer 5 USD to customer B. Bank simply electronically marks down 5 USD for customer A and marks up 5 USD for customer B. (The bank’s balance sheet remains unchanged)

Electronic transfer to account at another bank.

Customer tells bank to transfer 5 USD to customer B at Bank B. Bank simply electronically marks down 5 USD for customer A and tells Bank B about the transfer.

Bank transfers 5 USD reserves at the Central Bank to Bank B, Bank B then marks up Customer B’s account 5 USD. (Bank’s balance sheet has been reduced by 5 USD and Bank B’s balance sheet increased by 5 USD)

In all case clearly the debt remains.

-” Furthermore if deposits weren’t used to make new loans then why would banks compete for them and often pay interest on them in a normal environment?”

Banks are required to balance their balance sheets. In order to keep the payment system functioning the Central Bank will always lend money at the discount window so there are enough reserves to settle all IOU’s at the end of the day.

However borrowing from the discount window costs money and the banks would rather pay a bit less, so they will either borrow reserves from another bank at the interbank rate or go to the money market at the MM rate or encourage customers to deposit cash with them and the deposit rate.

So there is a hierarchy of interest rates and the banks will always try to find the cheapest way to balance their balance sheets.

Now, this is a key sentence, when a bank issues a loan it also creates a deposit which funds that loan. So, ignoring bankruptcies, there will always be enough reserves in the system to balance things out, but there will be imbalances between banks, and so the interest rates are used to sort out this.

I realise that is a very brief description. But it is the way things work.

So much for universities dispensing knowledge instead of myths!

For anyone insterested the Bank of England has a good pdf on how money is really created (i.e. not the money multiplier myth) http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Documents/quarterlybulletin/2014/qb14q1prereleasemoneycreation.pdf

If you already knew that link, then I wonder why you posed the question to me?

Just testing, eh?

No probs.

It is interesting that this has only recently in the last decade or so, been “made public” or admitted publicly by the Central Banks. And if you ask 99.99% of people they all solidly believe that banks take in deposits and lend them out. Even bank employees. I know, I’ve asked.

I guess that before the internet people had to believe what was disseminated to them. Nowadays a lot more questions are being asked.

The downside is that there is a lot of crap published on the internet too.

I didn’t know until you corrected me and I found this link (who said arguing on the internet was pointless).

I still don’t see why banks would ever want to attract deposits since that will create an equivalent liability it cannot be used to balance the balance sheet.

That phony scheme breaks as soon as there is a transfer to other bank. Issuing phony deposit on bank’s balance sheet does not adds up to reserves in CB or corresponding (nostro) account with any other bank. So to proceed the payment (customer borrowed to pay for something) to any other bank the lender-bank should get money somewhere. Phony deposits against new loans could work only as long as all payments originated from a new loan took place within a lender-bank. That’s obviously not the case in real life. Otherwise, why would any bank pay interest on deposits or sell bonds? And they sell a lot of bonds and attracts a lot of deposits. Why would they do that if they could “create new money” every time they underwrite a new loan to a customer. Personally I spend a few years at the Treasury of a commercial bank and I could certify – there is no such thing as phony deposit against new loan for commercial bank. Every time bank extend a loan, it MUST find financing somewhere outside. Lol.

Thanks for all the comments. I will respond to some questions raised later today.

Mo: I appreciate your observation that the tone is generally civil here. Thank you and everyone for helping keep it that way! :)

This article is over my head, to be perfectly honest. I have no argument with the fact that governments and individuals are drowning in debt, or the idea that money printing doesn’t create any real wealth. But I just don’t get the idea that fiat currency is not money, incapable of extinguishing debt.

Fiat currency absolutely IS money. Weak, prone to sudden crises of confidence, manipulable, and imperfect, but money. It is money because I have confidence that other people have confidence they can receive money for their goods and services, and go out and spend that same money and get goods and services in return.

It is money because congress (let’s use America as our example) says so, and people have confidence that congress has the power to say so. The collective belief makes it so. Gold is no different. We value gold because we expect other people will value it, too, and that confidence has remained stable for a long time. Gold has no issuer, true, but so what? The lack of issuer just makes gold a better form of money.

The dollar is money because Congress says so, and because everyone believes it so. It doesn’t matter where the little green scraps of paper come from, so long as their number is limited, and it doesn’t matter how the central bank keeps its books. Worrying about how the accounting takes place just complicates something quite simple.

Can debt be paid off with fiat? Can it be “extinguished”? Here, watch:

Me: Hey, bob, lend me a hundred bucks until payday, OK?

Bob: Yeah, sure, here you go.

Now my balance sheet (lol) shows a liability of 100 dollars, and his shows an asset of 100 dollars. Come next Friday:

Bob: You got that 100 bucks I lent you?

Me: Yup. Here you go.

Boom! debt “extinguished.” I don’t owe Bob a hundred bucks anymore. Can congress pay government debts with dollars? Yup, same way I paid Bob. Easy!

What if the national debt becomes too large to be paid? Congress can order the central bank to print up some green and pay those debts off with dollars, too, consequences be damned. As a matter of fact, that’s what it’s been doing these last several years.

What about the central bank’s balance sheet? Won’t it get awful big? Of course it will. But here’s a little reminder: It’s just a scrap of paper. It can be torn up, like Queen Cersei tore up the old king’s will in Game of Thrones, gone and forgotten like a fart in the wind. Extinguished. Nobody will come looking for the “debt” the central bank owes, because it doesn’t actually owe anybody anything. It is just an accounting fiction.

Congress can’t decree the sun to rise in the West tomorrow, but it can do anything it wants with the laws of men. Can it pay bills with dollars? Yes. If it runs out of dollars, can it print more? You betcha.

Can it burn up the central bank books in a big, ceremonial bonfire on the White House lawn, along with a few contrary economists? If they so choose! How about declaring ALL debts null and void, or “extinguished”? Of course they can, should they find the will and the people’s confidence to do so.

Sovereign currency has a value because

1. It is made legal tender to pay all debts.

2. The government insists that you pay taxes in it, so you must acquire enough of the currency to pay that bill. And note just how aggressive they are getting at ensuring the taxes are paid.

3. Faith and hope

Although effectively a chunk of the debt has been monetized through QE, they are not allowed to even indicate this. This means that we will be hearing “when QE is unwound”. However, I reckon it is a permanent monetization of the debt, and those bonds will remain on the books of the Central Banks forever.

But they cannot be written off, that is against the legal framework the banks operate in.

mossmoon, your point was that wealth is energy and therefore cannot be destroyed only transferred. Let’s say I have a Rolex and I melt it down for scrap. Not only have I used more energy in addition to the energy used to build the watch but I now have an asset that is less valuable than the previous one. Energy has been transferred but not wealth. I have simply destroyed wealth. No one has been made wealthier but I am certainly poorer now. You simply cannot define wealth in terms of energy.

Wealth is energy *in the context of using money to store and trade wealth.* When the money is destroyed the wealth is not destroyed, it is transferred. This is the point I am making that until now I thought was rather uncontroversial.

Wow! It is gratifying to see so many people respond to this article here (and on many other sites). It is important that the failure of debt-based currencies become part of the national (international!) conversation. I will try to respond to a few questions and comments here.

Mossmoon says that wealth cannot be destroyed. My argument was about capital, but a similar response works for wealth as well. What do you call it when a factory or house burns down?

cbarton asks if this is the typical collapse process. In one sense, yes. A debt-based currency collapses when the debt backing it becomes worthless. In another sense, not necessarily. Switzerand and the franc enjoy a position that’s atypical of a currency heading towards collapse: it is beloved by nearly everyone.

He also asks if rising rates are good. No, rising rates causes capital destruction by a different mechanism. Please see my theory of interest and prices (published here and elsewhere) where I discuss the rising cycle.

He asks if the SNB could buy gold. That would change the equation for sure. I would want to think about it more, but it will also cause the problem of a rising franc against the euro, thus squashing the commercial banks even more.

Windman says that the franc is strong due to faith, that hyperinflation is when faith is lost, and that it can’t happen. I think this view places too much faith in … faith.

horatio says it really well, and more briefly than I did. “At present, real assets are becoming less and less productive, nobody can invest and get a satisfactory return – only malinvestments can get made”. My only quibble is that I don’t think a strong currency harms exports.

JamesToronto says “nothing in this world is infinite, all promises that do not have a term limit are broken.” The catch is that the debt must be perpetual as there is no way to pay it off.

He also says “Most banks lend money at floating rates.” It is my understanding that banks own bonds. *Someone* owns lots of bonds, as there are certainly lots of bonds outstanding!

prattner says that the dollar is money, on grounds that the government says so. What if the government says that PI is defined as 3 (the government of the state of Tennessee did that, at one time) What if they say gravity repulses massive bodies? The government has no power to change physical law, or economic law.

He also says the dollar extinguishes a debt, but illustrates only what I call “getting one’s self out of the debt loop.” The debt itself does not go away. Now the Fed owes Bob the money.

This is a complex topic with lots of new concepts and ideas. It’s hard!

Thanks everyone for reading and engaging! :)

He also says “Most banks lend money at floating rates.” It is my understanding that banks own bonds. *Someone* owns lots of bonds, as there are certainly lots of bonds outstanding!

The Fed, BoE and BoJ own a vast chunk of the bonds through the QE purchases. The others are mostly held in the shadow banking sector by pension and insurance companies, who have a lot of cash to place somewhere, and government bonds are pretty much the only place this can be stored. Accounts at commercial banks do not meet the requirements, FDIC only guarantees up to a very small limit.

It would be interesting to see how the dynamics would change if they could have accounts at the Central Banks.

Keith

Agreed entirely that a strong currency does not harm exports, other than in the short term. Exporters who produce real value soon adjust as do their customers.

I think exporters are harmed depending on the busns sector. In my humble opinion both windman and keith are right and wrong in some ideas. Yes there is too much faith in faith but history teaches us that a system collapses due to 3 main reasons

1 the braveheart wallas does not die on the table of torture due to bribery by the king and the elites join the masses against him for their own benefit

2 we have been noticed cheating so we pretend that a better system has been found and we adopt it but again with same background rules

3

3 there is a new kid in town with better tech power etc and we either follow or we go to war

Yes gold is money but the masses have been brainwashed so so much that not only acceptsthe paper as money they donnot understand what we are talking about Apart ofall this i have a question do negative interest rates imply a way to give notes by the cb to the government as income without the need by the government to issue more bonds in the future? And thus upon the maturity of the bond the liability on the cb side as cash notes remain but the gov has a profit so can extinguisg the bond ie pay it back plus another bond of past seqience

You seem to be confusing negative rates on bonds with negative interest rates charged on reserves at the CB.

The negative rates on bonds has arisen because the bonds are selling in the market at a higher price than the NPV. At time of issue the bonds were certainly not offering negative rates, but some small percentage dividend, which the government has to pay.

The negative rates charged on reserves at the CB does not apply to all reserves, and is designed to prevent the inflow of forex into CHF, holding the currency down.

The small amount of interest charged by the SNB will not make a significant difference, indeed will not come even close to offsetting the huge paper loss on foreign bond holdings.

To windman

Thank you for your reply! I do not understand then how come and 2 friends of mine bought german bonds and accepted to get less money upon maturity because the rates were negative! I could not believe in my ears! I would never do this. So they either lie or they bought something else without knowing it? Oh by the way the NPV is negative! So what for the average Joe?

I had to read the article twice, but I think I get the gist now :).

Essentially, when a monetary regime’s interest rates fall to zero/negative, the currency no longer works as capital, since there are no longer borrowers who are willing to give you income in exchange for that currency (capital). Since capital ownership’s main attraction is the ability to exchange it for income, this INABILITY to exchange the currency for income means the currency is NOT capital anymore.

Therefore, there is no reason to hold that currency, and, once the holders of the currency awake to that fact, they will quickly diversify out of it. So, that is where the currency collapse comes from, as a side-effect of the extreme interest rate regime.

Keith,

If your argument proves to be true (you have convinced me) then NASOE will eclipse all other economic theories and you will be hailed as Caesar. If you are wrong you will be put in stocks and pelted with rotten eggs for the rest of you life. You are a brave man.

Thanks for the vote of confidence and the dire warning! :)

Btw, I have no affiliation with NASOE.

Hats off to any scholar who stands by his convictions.

Having said that, there are lots of dirty tricks CBs, backed by their working boyz and galz, can pull down the track, and there is no telling how vicious they will get if cornered.

They way I see it, the fundamental problem is that people don’t save in real money, which makes us all extremely vulnerable and dependent on our political leaders and bankers for providing the means of exchange.

Barter is too inefficient for sustaining a complex society, and the woeful absence of real money in people’s pockets will keep us all dependent and vulnerable on so-called “solutions” that are anything but.

cbarton: Thanks.

I agree, and I’ve said it many times. Never underestimate how many tricks they have up their sleeves…

Yes, Keith, they certainly do.

I have mulled over this long and hard, and the more I am looking at possible solutions, the more exposed and vulnerable we, the people, appear to be.

Because of our dependency on a currency for an efficient mean of exchange, we are easily and hopelessly being held hostage by those who issue, control and manipulate the value of that currency.

To escape their clutches, their manipulations and dirty tricks, we would first need to reject their currency as our means of exchange, and start using instead natural forms of money, as provided by the Founding Fathers and the Constitution of the United States. If enough people started doing that, used gold and silver in settlement of debts, instead of the current promissory notes, then the game would be up and the parasite classes would have to start looking for honest and productive lines of work, or starve.

People could actually make this happen, through peaceful resistance and the rejection of the currency through which they are being used and scammed by the parasite class. Alas, in the absence of real money in their pockets, there is little chance of that, so the beatings are set to continue until morale improves.

Actually, the people’s acceptance of using what nowadays pass for money (dollars, euros, roubles, and what have you) is analogous to what is known in game theory as a “dollar auction.” Once one agrees to participate in the game, the dollar auction, one gets hopelessly trapped with the very first bid. Almost invariably, even the winner of the auction overpays in a hollow victory. It is an insidious and hopeless game.

Many have argued that the most compelling analysis of the nuclear arms race, for example, is in terms of the dollar auction, not to mention the insidious nature of wars, where, once started, both sides feel trapped, and quitting becomes almost impossible, no matter how grave the losses might be, because of the compelling rationale that “if we quit now, all our efforts and sacrifices will have been in vain.”

The same sort of dynamics appear to be in play with the use of intrinsically worthless fiat currencies as a means of exchange. They are killing us with them, but we cannot quit using them, because we would suffer immediate disadvantages and losses that we are poorly prepared for and are unwilling to take.

Notwithstanding, as the dollar auction quite clearly illustrates, the only real solution is to avoid and refuse participating in such games.

Individuals can still do this, converting and holding their savings in real money and tangible assets, and avoiding, as much as possible, counter-party risks.

But as a society? I doubt it. On masse, as complex societies and economies, we appear hopelessly trapped. The vast majority of people are not prepared and are in no position to switch to a practical alternative. Hence, our collective beatings are set to continue, and we will just have to be on the look out for any signs of improving morale.

Are there any updates on the outlook for CHF? What delayed its collapse?

Can you provide an analysis of why this did not come to pass, as of yet?