I Know Usury When I See It, Report 4 Aug

“I know it, when I see it.”

This phrase was first used by U.S. Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart, in a case of obscenity. Instead of defining it—we would think that this would be a requirement for a law, which is of course backed by threat of imprisonment—he resorted to what might be called Begging Common Sense. It’s just common sense, it’s easy-peasy, there’s no need to define the term…

This is not a satisfactory approach. Leaving aside concerns with undefined terms as the basis of sending someone to jail, it is an admission that one cannot define the term. As Richard Feynman once said:

“I couldn’t reduce it to the freshman level. That means we really don’t understand it.”

Obscenity has an analog in monetary economics: usury. Most people think usury is a bad thing, like obscenity. But they can’t define it.

At dinner with an investor on Friday, this concept came up. We’ll call him John. John is in the middle of reading Barren Metal, by E. Michael Jones. John has also read a draft of a book that Keith is awaiting to see, from a mutual friend and fellow monetary traveler. The draft also has a chapter on usury, so the idea was topical at New York’s Arno Ristorante.

John thought the concept of usury could be a matter of degree. For example, if a loan shark lends you $20, and demands $50 repayment after a week, most people would say that’s usury. Or a young unskilled worker goes to a payday lender to borrow $100, and the interest charge is $15 for two weeks (which works out to be around 400% per annum). Payday lenders are under pressure from regulators, precisely because this strikes most people as usurious (we are not fans of outlawing everything we don’t like).

How about if you buy a flat screen TV on a credit card, and pay it off over two years with 20% interest? This is pretty bad, if you think about it, and is it not the same in principle? What about if an 18-year old kid buys an old used car and the dealer charges him 10% for financing?

Or a student borrows over $100,000 to go to university to get the job he wants?

If you know it when you see it, which of these do you know is usury? Where do you draw the line?

We think that the very fact that this question of the line shows that the concept is missing something. Two somethings: genus, and differentia. A proper definition gives the genus, which is the category of thing that the concept comes from. For example, in usury, the genus is lending. Usury is a kind of loan. If there is no loan, then it’s definitely not usury.

The definition must also give the differentia. This is what makes the concept unique, and not the same as all other things in its category. Usury is a loan, but only certain loans are usurious. There is something different from usury compared to all other loans. What is the difference?

The loan shark has an element of brutality. If you don’t pay, he will break your kneecap. But this element is missing from the payday lender. The payday lender is taking a big bite out of the worker’s income, like a tax. Is that it? No, the credit card company isn’t taking that much, as a proportion of the consumer’s income. The student lender has the student over a barrel—tuition is so high that he cannot pay without financing, though the loan shark does not. So what is the common element?

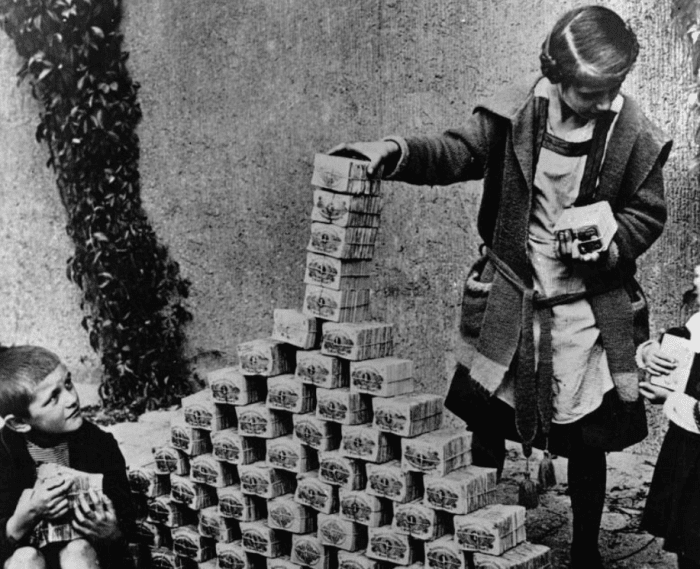

If one goes through all of the obvious factors, one gets no closer to the differentia of usury. So, let’s tie it to a concept we have written much about. Inflation.

Inflation (no, it’s not rising quantity of dollars, nor the commonly believed outcome of rising prices) is the counterfeiting of credit. It is when one or more of the following occurs: the lender does not know he is lending (just ask someone with a hundred dollar bill in his hand if he thinks he is a lender!), the lender does not agree to lend (just ask someone who sold his Treasury bonds, on grounds that the government is going to default sooner or later, and who now holds a stack of hundred dollar bills), the borrower lacks the means to repay, and/or the borrower lacks intent to repay.

In other words, legitimate credit is a win-win deal between a willing lender and a borrower who is in a position to pay.

What can we glean from inflation? Usury has some overlap, in some cases the borrower is in no position to repay. Inflation is analogous in some ways, but not the same concept.

It is analogous, because both are a type of bad credit. In inflation, the lender is losing economic value sooner or later. The lender is getting a bad deal, no matter that the first lender can sell the loan off to another investor, who sells it to another, etc. At the end of the day, as cold ashes follow a hot fire, deflation follows inflation. Deflation is a forcible contraction of credit. A default or haircut or bail-in or cramdown or debt-for-equity swap will occur.

In usury, it’s the borrower who loses.

In inflation, the lender would be better off simply by not lending (which is why governments disenfranchised savers, and took this option away from them). And in usury, the borrower would be better of simply by not borrowing. This is no subjective opinion. Let’s consider what this means.

In contrast to most of the examples given above, suppose Productive Growers Corporation borrows $2 million to plant its crop. After 4 months, it harvests the crop at a cost of another $800,000 and incurs interest charges of $200,000. Productive sells its crop for $8 million, thus it nets $5 million.

This is an example of good borrowing. Certainly, Productive is better off for having borrowed that $2 million.

We can begin to see the essential characteristic here. One more example may help cement it. Suppose David Devlor borrows $1 million to build an apartment building with 25 units. He rents each unit out at $2,000 a month. After maintenance and costs—and after setting aside a budget to pay for capital replacement such as air conditioning—he makes $20,000 a year per unit, or a total of $500,000 a year. Clearly, $500,000 a year in income justifies a $1 million loan.

And we can calculate how much the income is worth in the present. If the interest rate is 10% a year, then the Net Present Value of $500,000 a year is $5 million. David borrowed $1 million to finance the creation of a $5 million asset.

David added a $5 million asset and a $1 million liability to his balance sheet. In other words, he added $4 million in equity. Good borrowing is when it creates a greater asset than the value of the liability, when it adds equity.

And that leads us to it. Usury is a loan when the borrower is subtracting equity.

If one borrows to consume, by definition one is subtracting value. However, note that the case of the university degree is not trivial. A degree increases the salary one can earn over a lifetime. And one can calculate its net present value. If the net present value of the higher earnings is (significantly) greater than the loan, then it’s not usury. It’s a good deal for the borrower.

However, this leads us back to a topic we’ve addressed many times, especially in Keith’s theory of interest and prices. When the government manipulates the market rate of interest, it distorts incentives, and even human perception of matters economic. This market rate is the only rate available for discounting future cash flows, and hence to assess the net present value of an asset. Including the university degree asset.

The apparent economic value of the asset rises, with each drop in the interest rate. But this deceives people. The calculation of NPV of a university degree might be $200,000, and so the loan of $100,000 might appear to add value. However, if one discounted future earnings with the interest rate that would occur, if the market were free of central banks and their bloody irredeemable currencies (which there is no way to know exactly), one could very well find the $100,000 student loan to be usury.

Finally, non-usurious loans can become usurious. Each time the interest rate drops, the NPV of outstanding debt—which was borrowed at higher rates—increases. This could make the liability grow bigger than the asset.

The NPV of the asset does not necessarily grow with it, as it becomes more difficult to earn the same dollar of revenue when competitors are stimulated to add capacity by the falling rate.

There is an elegant parallel between inflation and usury. They are two kinds of bad credit, assessed from the perspective of the lender and of the borrower, respectively. And while both did occur when gold was the asset backing the banking system, they grow like cancer when gold is banished and irredeemable credit becomes the ersatz backing.

Supply and Demand Fundamentals

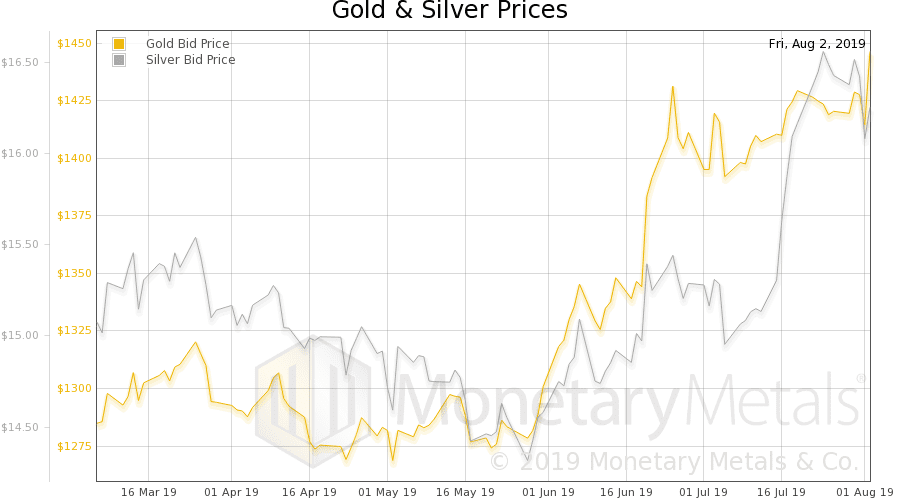

The price of gold went up $22, while the price of silver dropped ¢17.

The big news this week is that the yield on all German government bond maturities is now negative. They are also all negative in Switzerland. And in Denmark, all maturities out to 20 years are negative. Interest rates are dropping rapidly in the US as well.

Remember the stories about inflation, rising quantity of dollars, Fed losing control, and the certainty of higher interest rates? This was way back in fall of 2018. In our report of 4 February 2018, we said:

“The falling-rates trend will resume soon enough. The only question is how big a crisis occurs before the Fed abandons tightening and aggressively reverts to loosening.”

By that time, the rate on the 10-year US Treasury had dropped a bit from its prior level around 3% (and its peak of 3.2%). It was then around 2.7%. The consensus, especially among the gold community, was for higher rates. Now this same Treasury trades under 1.9%. That’s a big drop in rate, around 42% from the peak.

It’s also a big capital gain for bond speculators. How will these wealth-affected people boost GDP, what will they buy, how will they consume the capital now forked over to them?

Keynes was smirking when he said “…not one man in a million is able to diagnose.” He proposed to drive the interest rate to zero, to kill the investor. He counted on the investor not seeing his own death, because the investor is looking at the flip side of interest going to zero: asset prices rising to infinity.

If you wonder why anyone would buy a bond with a negative yield (aside from the problem of being disenfranchised), this is why. A bond—the longer the maturity, the better—is a great vehicle for speculation. One can buy low-yield bonds, in a speculation the yield will go to zero. One can buy zero-yield bonds, in a speculation the yield will go negative. And one can buy negative-yield bonds, in a speculation the yield will go negativer.

We have but one thing to add. The temptation to usury increases with each drop in the interest rate. Perhaps the loan shark does not drop his rate, and maybe the payday lender. But there are countless ways to borrow on a self-destructive basis. If Tommy Temptation says “no” at a rate of 10%, maybe he will say yes at 8%. And, if not at 8%, perhaps at 6%…

Monetary Metals is excited to be bringing the first gold bond to market. Please contact us if you are interested in investing.

Now let’s look at the only true picture of supply and demand for gold and silver. But, first, here is the chart of the prices of gold and silver.

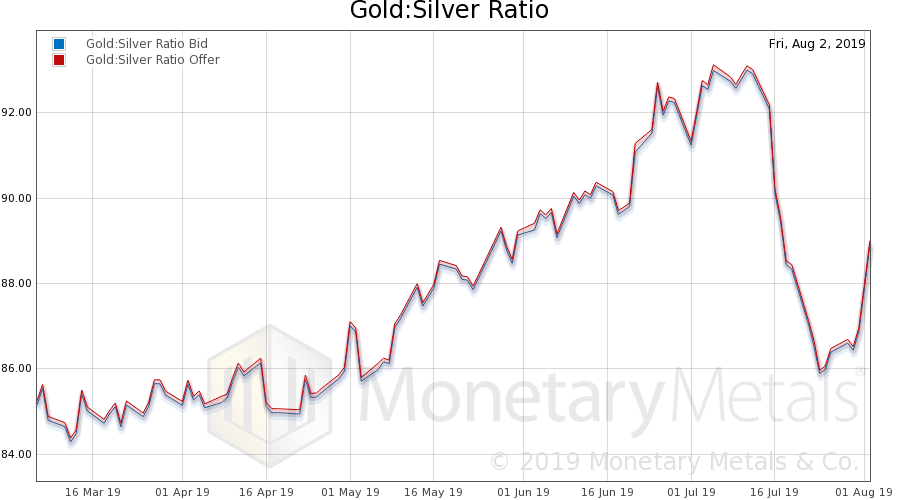

Next, this is a graph of the gold price measured in silver, otherwise known as the gold to silver ratio (see here for an explanation of bid and offer prices for the ratio). The ratio rose this week.

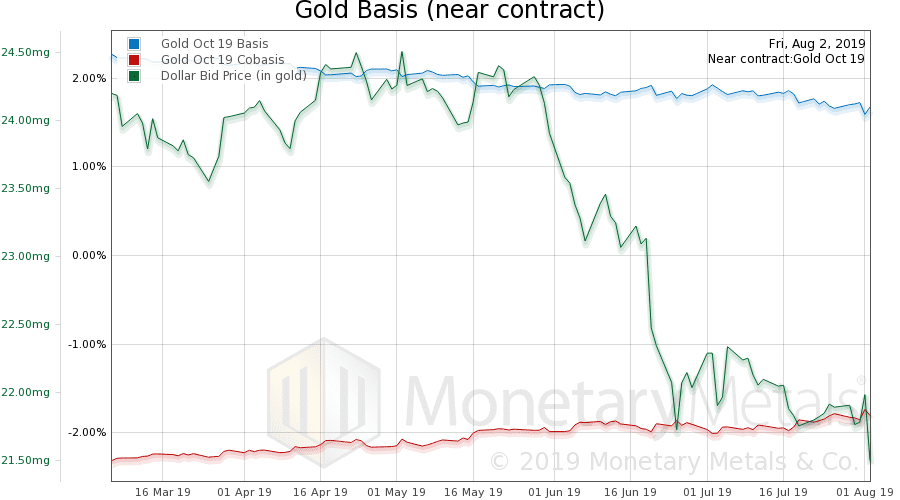

Here is the gold graph showing gold basis, cobasis and the price of the dollar in terms of gold price.

That scarcity (i.e. cobasis) sagged just slightly.

This week, the Monetary Metals Gold Fundamental Price is up $15 $1,436. This is still below the market price.

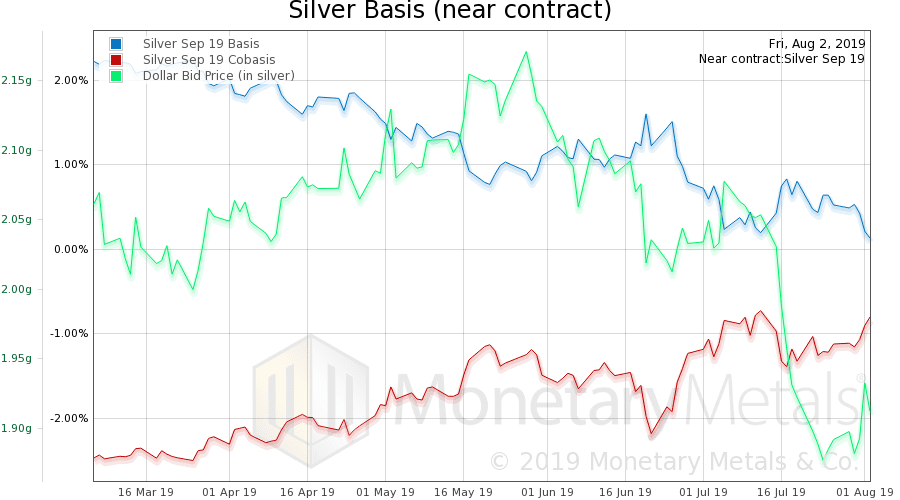

Now let’s look at silver.

The scarcity (i.e. cobasis) is up a little, but not that much.

Last week, we mentioned the drop in the Monetary Metals Silver Fundamental Price, saying:

“…[it] puts the silver fundamental price below the market price.”

This week, the fundamental dropped from $16.21 to $15.72.

© 2019 Monetary Metals

My understanding is that the Bible et. al. condemned as usury the lending of money at *any* (positive) interest rate, and that the meaning has shifted since then to be as you describe, lending at a usurious (unreasonably high) rate.