There’s Your Hyperinflation

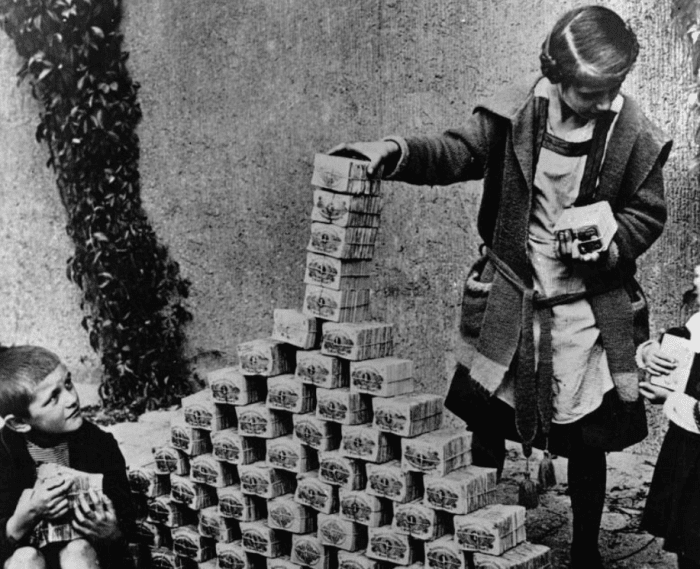

Hyperinflation is commonly defined as rapidly rising prices which get out of control. For example, the Wikipedia entry begins, “In economics, hyperinflation occurs when a country experiences very high and usually accelerating rates of inflation, rapidly eroding the real value of the local currency…” Let’s restate this in terms of purchasing power. In hyperinflation, the purchasing power of the currency collapses. Before the onset, suppose one collapsar buys ten loaves of bread. Soon, it buys only one loaf. Shortly thereafter, it buys only one slice. Next, it can only purchase a saltine cracker. Pretty soon the collapsar won’t buy any bread at all. Stick a fork in it, it’s done.

Many critics of the Federal Reserve, the European Central bank, and others have predicted that this end is coming soon. They have been frustrated as prices are clearly not skyrocketing. For example, the price of crude oil was cut almost in half (so far). There’s little to see if one looks at the purchasing power of the dollar, euro, Swiss franc, etc. Purchasing power, as conventionally understood, is doing just fine.

Fed apologists are happily cooing about this. Last month, Nobel Prize winning economist Paul Krugman said, “This is actually wonderful.” Last year, he was gloating, comparing people who predict runaway inflation to “true believers whose faith in a predicted apocalypse persists even after it fails to materialize.”

And yet, all is not well in the realm of the central banks. Krugman may be right about prices, but nothing is wonderful. The economic downturn, which began in 2008, has been so bad that central banks persist in their unprecedented monetary policies. So if purchasing power isn’t collapsing, where can one find evidence of the problem?

Yield Purchasing Power (YPP) shows how much you can buy, not with a dollar of cash, but with the earnings on a dollar of productive capital. No one wants to spend their life savings or inheritance. People are happy to spend their income, but not their savings.

To come back to the analogy of the family farm, people should think in terms of how much food it can grow, not how much food they can buy by selling the farm. The tractor is good for producing food, not to be exchanged for it. Why, then, do people think of the purchasing power of their life savings, in terms of its liquidation value?

If they want to live long and prosper, they should think of their yield purchasing power. Their hard-earned assets should provide income. And it is here, that hyperinflation has set in.

Previously, I compared two archetypal retirees. Clarence retired with $100,000 in 1979, and Larry retired with $1,000,000 in 2014. Clarence was able to earn 2/3 of the median income in interest on his savings. Larry was nowhere near that. He would need over $100 million to do the same. In 35 years, the YPP of a 3-month CD fell more than 1,000-fold.

The collapse in YPP suggests an analogy to hyperinflation. Look at how much capital you need to support a middle class lifestyle. Measured in dollars, the dollar price of this capital is skyrocketing.

This skyrocketing price of capital has the same effect as hyperinflation: it undermines savings and causes people to eat themselves out of house and home.

What does this mean for anyone with less than what they need to support themselves—$100M and rising? They must liquidate their capital, and live by consuming their savings. It’s terrifying to anyone in that position—which means anyone in the middle class.

This problem is not well understood, because it masquerades as rising asset prices. The first tractor to go to the block fetched $1,000. The second went for $2,000. The farmland may fetch a few million. Everyone loves rising asset prices, and so in their greed and euphoria they miss the point.

Keith is speaking at FreedomFest in Las Vegas this week.

This article is from Keith Weiner’s weekly column, called The Gold Standard, at the Swiss National Bank and Swiss Franc Blog SNBCHF.com.

Have been trying to get my head around Prof. Fekete´s concept of capital destruction via falling interest rates for some time. This illustration of cause and interest rate effect gets me much closer to a gut appreciation of this important concept.

Henry

What a great article. Thank you for explaining this!

Exactly!

Hi Keith, you are making the same mistake here as in the blog entry about real rates. Clarence is not able to cover about 2/3 of the annual median income with interest income. His interest income is negative. He is loosing purchasing power to inflation. Larry is clearly better off because at least his purchasing power is not shrinking. The level of nominal yields is irrelevant for the arithmetic, but I concede that it has a behavioral component. However, this is no hyperinflation. The purchasing power of money is measured as the weighted average of individual exchange rates between money and goods and services. With regards to goods and services the purchasing power of money has been quite stable. With regards to finanical assets and various goods that cannot be reproduced (works of art, real estate in prime location) it is a different matter.

Are you saying that the Clarence example is not valid because inflation in 1979 was running at a rate higher than risk-free interest? Furthermore, are you saying that we are no worse off today because it is still the case that (objective measures of) inflation are higher than the risk-free rate?

If that is what you are saying, it seems very counter-intuitive. How can prosperity spring from a system in which purchasing power is lost by anyone who attempts to save at the risk-free rate? If the only way to prosper is through risk, then that is a zero-sum game, and it produces no net prosperity.

Hi bgoldman,

I’m not saying any of that. All I’m saying is that the nominal interest rates does not matter for a saver. What matters is the real rate. Clarence is not better off than Larry just because he receives a high nominal yield while Larry receives a small nominal yield. Fact is that Clarence sufferes a high real loss of purchasing power while Larry is not. Clarence is not covering 2/3 of the median income with interest income. He is not covering any income at all. Instead, he is loosing purchasing power of his saved wealth, while Larry is not.

Thanks for your comments.

dfaltin and bgoldman: Learning a new idea is easy. Just listen and think about it. However, a new paradigm is much harder, because you have to check–and challenge–assumptions, including deeply held and implicit assumptions that are not fully stated.

The concept of yield purchasing power is a paradigm shift. It’s easy to state, “Look at what you can buy on the interest, not on liquidation of the capital itself.” I understand that it is much harder to get your head around. Nevertheless, I believe it is of paramount of importance to talk about this idea and add it to the conversation.

Hi Keith,

I like the idea of thinking about such new concepts. However, I think your calculation does not work out. Instead of two persons at different points in time with different amounts of savings, we can simplify the example and think of Larry who still has 1 Million USD on which he receives 0.03% nominal interest with no inflation, i.e. nominal = real interest. Larry lives in country A. Now think of Peter, who lives in country B. He also has 1 Million USD he received 3% of nominal interest, but suffers inflation of 5%, meaning that his real interest is -2%. Who is better off? Peter with his high nominal yield or Larry with his very low nominal yield? Clearly, it is Larry, who is also better off incomparison to Clarence in your example.

dfaltin,

It’s important to understand exactly what Keith is talking about. He is not asking what is the real return on the investments. Clarence is using his $100,000 of capital to live off of. He is not going to add to it from the investments. Therefore, the prevailing rates provide him with 2/3 of the median income of the time. He is going to consume this income and not reinvest it. 2/3 of the median income is very good for a retiree who owns his own home. To live off investments in 2015, however, retirees need multiples of $100,000 at the same *risk* level to ensure 2/3 median income. So, it’s obvious retirees will either have to increase their risk or eat into their savings.

Best.