Heat Death of the Economic Universe

In physics, the heat death of the universe occurs if all matter is moving apart. If it happens, it will be long after we’re gone. But there’s a troubling move towards the heat death of the economy. There is a diminishing return on debt. CEO Keith Weiner gives a lecture for the Ayn Rand Centre in the UK where he deconstructs the end game of the dollar system. Keith answers questions on depressing margins, Modern Monetary Theory, how much gold the US has, the credit gradient and more.

In this talk, Keith also discusses

- Nixon closing the gold window

- Inflation and other threats

- Exponentially rising debt

- Where are the bond vigilantes?

- The Credit Gradient

Make sure to subscribe to our YouTube Channel to check out all our Media Appearances, Podcast Episodes and more!

Transcript of Heat Death of the Economy Talk and Q&A

Sometimes I despair of what passes for economics education nowadays, as the apologists for the monetary regime become pretty aggressive. And now, is everybody familiar with modern monetary theory, so called? Which isn’t modern, it isn’t really about money, and it’s certainly not a theory in the sense of something that explains observations about reality. It isn’t that. It’s basically the same old socialist rubbish gussied up in a chic new brand and then they put wrapping paper on that and a big shiny red bow. And they’re very pugnaciously, saying basically that the government can print and spend as much as it wants as long as it doesn’t cause too much inflation. The critics of this regime agree. Not with the idea that you should just print as much money as possible. They don’t really put that forward, but they agree that basically the primary, if not the only bad thing that can happen is consumer prices will go up too much. So they say, well, don’t do it too much because the consumer prices are going to go crazy. And then the socialists, yeah, we get it right, don’t have too much inflation, but we can print just below that and it’ll be okay.

And there’s a magic threshold, and above the threshold, there’s too much inflation. If it’s below the threshold, it’s just enough inflation? So much inflation we can get away with and no more? None of these things are really named or voiced explicitly, but the critics agree with the propaganda that the problem is inflation, so called. And I’m here to say that, as I did in my last talk with this one, which has a very different focus. That ain’t the problem, not at all. Now, we have skyrocketing consumer prices at the moment, I think largely due to non monetary forces. So here in the UK, you’ll pass two really bad laws at around the same time. I think 2017, 2018. One forces the domestic consumers, especially the big industrial power plants and heavy industry, to switch from oil and coal to natural gas. And the other one shut down all domestic production of natural gas. So first, force everybody to use it, secondly force everybody to have to import it. So that’s a one two punch.

And then with COVID, we have lockdown and then what I call whiplash from unlock. And then suddenly you can’t ship Christmas tree ornaments from China to Los Angeles. You can’t ship natural gas or anything else. And then the net result, very predictably, is that the price of natural gas skyrockets. What if it went up ten x or something like that? It went up enough that one of the things that produces natural gas is fertilizer. It went up enough that it was too expensive to manufacture fertilizer anymore. So domestic fertilizer production shutdown, that has not affected the price of food so far because right now we’re eating the things that already were grown. But next winter, things may take a turn for the worst. People will call that inflation and say it’s monetary. No, it’s a result of three bad laws. One, banning domestic natural gas production. Number two, forcing increased consumption of natural gas. And then number three, the response to covet and the lockdown. Whatever you think of the medical issues, economically, it has been absolutely horrific. And then the consequences will still be rippling through for quite some time.

So anyway, the problem isn’t rising consumer prices, certainly not from the monetary side. It’s something else. So the concept for this talk, the Heat Death of the Economic Universe. I’m very grateful to Razi and the Ayn Rand Centre UK to be recording it so we can get this on tape, because I think it’s an important concept.

Heat Death and Positive Feedback

Heat death of the economic universe. What am I talking about? Is everybody familiar with the physics concept of the heat death? So in physics they believe that the universe is expanding. I’m not a physicist, but I could quibble with that and say, I’m not really sure that makes a lot of sense. And there’s some conclusions of that whole theory that just the deeper you go, the more bizarre it gets. But just to go with it for purposes of this talk, the idea is that if everything we witness the telescopes is moving away from us, that’s the interpretation of the observation. Observation is that everything is redshifted. We know from Doppler, redshift means it’s moving away. There may be other reasons to redshift have nothing to do with that. So the universe is expanding, and the idea is that if it’s expanding faster than a certain rate, which is its escape velocity, then even though gravity is pulling it all together again, the velocity is greater than that, and everything is going to escape and get farther and farther and farther and farther apart forever.

And that means that as matter and energy becomes less and less dense than one by one, the stars wink out as they reach the end of their life. But there’s no further new star formation because everything is getting too low density. And so then the universe gets colder and colder and colder, darker and darker and darker, asymptotically approaching absolute zero. And then that’s the so called heat death of the Universe. I like physical analogies to the economy because it gives the mind a way to kind of think about something that otherwise could be pretty intangible and pretty abstract. So let me talk about how and why this relates to the economy. So first, getting back to inflation for a minute. If the problem was inflation, the problem was we print and double the quantity of money, so called money is a dollar. It’s actually not money, it’s an irredeemable credit, but everyone calls that money. We print a double the quantity of dollars and that should in theory, roughly, with leads and lags and maybe not exactly double, but approximately double the general price level. If that were the problem and the full extent of the problem, there’s no real finite terminus to that. I mean, it’s been going on for 100 plus years, going on for another 100 plus years to go on for a thousand years. It’s really, actually not that severe problem. Inflation would be a tax.

So if you say to the average critic of the regime, inflation is a taxe. Yeah, absolutely, it’s a tax! You look at that and say, wait a minute, what is VAT here? 20% What’s income tax here? 50%? So not only does it not have a finite terminus, it can go on forever. It’s a tax. And actually not the biggest tax and not even the second biggest tax, maybe the third or fourth biggest tax. So it shrinks in significance. And if nobody gets outraged about the monetary problem, you can see why you just told them it’s actually not that big a deal. It’s annoying. When life goes on, they tax you. And the two things that are certainly in life, death and taxes, okay, tax rate, whatever. The physics analogy suggests that I’m trying to go in a different direction and suggest there’s actually a finite terminus to all this. It’s not just simply because prices double every eight or ten years or whatever it is, and you keep doubling, which could go on forever.

Every once in a while you add a zero to it. I mean, look at prices today. What is a flat in central London? A million pounds? A pound used to be 16 troy ounces of sterling silver. A million pounds of that stuff is like 30 tons. That’s an enormous amount of silver. And yeah, obviously it’s nothing to do with silver anymore. Prices just double, double, double. But it hasn’t really caused society to collapse. It hasn’t caused any calamity. We’re richer today than they were when a pound actually meant 16oz of metal. Okay? So 100 years from now they’ll be talking about a billion pounds for a flat, whatever, but salaries will be a million dollars or £17 million for a barista at Starbucks. So everything changes proportionately. According to their theory not according to mine. Okay, so what?

The way I want to explain this and why I want everybody to think about this is that the economy is not a linear system. It just simply isn’t true that, okay, you double this variable, this independent variable, and therefore you’re going to double dependent variable. So in math you say f of x equals some function of x, right?

And now if you change x and say x doubles f of x equals two x or whatever, this isn’t how things in the economy work, and that the economy is full of nonlinear systems. What do I mean by nonlinear? I don’t just mean straight line, I mean even a curve. In a certain sense, you could say linear, because it’s contiguous, because it’s stateless. So from computer software, a stateless function is one where you call this function and the output depends entirely on whatever you pass it as inputs. A statefull function, the opposite. It has memory. So let’s say you feed people cheap credit before 2008. How do they behave then? You offer them the same cheap credit in 2009. You get a very different outcome because people remember, they’re not goldfish. A goldfish is swimming along in a tank, I’ve been told, I have no idea if it’s accurate, 6 seconds is the limit of their memory. So if you wait 7 seconds and offer the goldfish the same stimulus, it should, if that theory is true, respond the same. And then you wait 7 seconds to do it again. It doesn’t learn because it only remembers 6 seconds.

But people have memories that last a lifetime. You know, there are places in the world, Austria, for example, that had hyperinflation in 1956, that is very much living memory. There are people that remember that. And whatever mistakes individuals were making before 1956, the people who remember that may behave quite differently, and their kids probably as well. And maybe by the grandkids that are ready to repeat the same mistakes, the institutional memory or the population memory is forgotten. The economy isn’t linear like that. So I would ask the following question. Suppose you have a rock star who played his guitar, Jimi Hendrix, and he goes up to the amplifier and he holds the guitar two inches from the amplifier. What frequency does he get out of that and how loud does it get? There isn’t a single answer to that. Because what happens is it will get louder and louder and louder because the sound coming out of the speakers is vibrating air, which hits the strings. It makes the strings vibrate. The strings then have magnetic pick ups that go and become an electrical signal that feed into the amplifier and amplify and go back into the speaker, which is now vibrating even more.

And it would keep feeding back and feeding back and feeding back until the amplifier caught on fire, unless they put a special circuit in to detect this and stop it. So there isn’t a single answer that, well, how loud does it get? How loud it gets depends on where it is. It’s a positive feedback loop cycle, and it keeps feeding back and feeding back, leaving aside that there’s a circuit to clip it. And the economy has this positive feedback loop that relates to or as part of the causal mechanism for what’s leading to what I call the heat death. I’ll explain what I mean by that in a minute.

The Adulteration of Money

So let’s start with by degrees, the monetary system was adulterated, was perverted in various ways. So there was a time when money meant gold or silver, and currency was a deposit of money, ie. of metal. You brought your metal to a bank and deposited it, and everybody understood you had a right to have the return of that metal, or you could pass a piece of paper to somebody else, and that person then had the right to redeem that metal.

There wasn’t a price that a dollar or sterling was set at in terms of metal, or metal was set in terms of the currency. It was just a standardized unit. It’s like on the Internet. You have a byte and you have a packet, you have all these things. It’s not saying that your application should be limited to that. It’s just saying we just standardized these things so all the different applications can talk to each other. A packet is 1024 bytes or whatever it is. But then by degrees, they preferred it adulterated to introduce central banks in the United States. They introduced a central bank in 1913 to begin manipulating things and so on. 1933, President Roosevelt infamously made gold illegal to possess. It was a criminal act, just like cocaine is today. As in go to prison, if you get caught possessing, it. Voided all the gold leases and contracts, including bonds, confiscated all the gold, and then the dollar became redeemable to Americans, but continued to be redeemable to foreign governments. But I don’t think foreign governments really were in the mood to be moving gold out of the US. And back to Europe in the 1930s because things were leading to war.

And the US is probably a safer place to have your gold than a place that was likely to be invaded or bombed or whatever. But after the war, the US. Dictated this insane monetary treaty at Bretton Woods in 1944 and basically said to the rest of the world, here’s the deal, and you will like it, because we’re the only ones standing with a productive economy and guns, and here’s the terms. Everyone thought that was good for the US and bad for the rest of the world. They were half right. It was bad for the rest of the world. The architect was a guy named Harry Dexter White, who was later proven to be a tool working for the Soviet Union. And this system was his idea of how to undermine and destroy America and Western civilization. It’s not actually good for America at all, but when people have a win/lose, zero sum mentality, if it’s bad for one party by a process of deduction, it must be good for the other they don’t really understand it’s actually lose lose. But the lose on the American side is a different kind of lose. It’s like when a thief steals from a victim. The thief isn’t winning either.

Anyways, the system was unstable, and the European powers, in particular France, were redeeming greater and greater amounts of gold from the United States infamously France sale to Battleship into New York Harbor to offload pallets of dollar bills and on load pallets full of probably much smaller pallets full of bricks of gold. And so the gold was being drained at a rate of something like 100 tons a day, I want to say, or a week. Something like that was an enormous thing. The US. By that point was down to 8000 tons. You’re losing gold at a rate of 1000 a week. You can quickly see it’s going to run out of gold. So this crisis, the leading Keynesian thought that Nixon should reprice gold, the actual answer is, and if you’re going to have central planning, all the rest of that, he should have changed the interest rates. And Milton Friedman was whispering in Nixon’s ear, and by that I mean writing letters saying he should default entirely. So Samuel, the Keynesian of the day, had actually penned an oped for the Washington Post saying that Nixon reprices gold, and they’re just waiting for the numbers to see what he’s going to do.

And Nixon just completely defaulted on it. So anybody who hasn’t seen the video of that on YouTube it is utterly mendacious. I’ve directed Secretary Connolly to temporarily suspend blah, blah, blah, blah, blah. This isn’t going to affect you unless you travel abroad. Blah, blah, blah, blah, blah. What a lying sack of you know what that Nixon was. The dollar becomes irredeemable.

Focusing on the Wrong Problem

Most people at that point focus on what? Consumer prices. Because that’s the only thing to focus on. That’s the only symptom that matters. That the only thing the system does, is it makes consumer prices go up. And after 1971, consumer prices went up. The end. Isn’t that terrible? And I’m here to say, okay, yes, consumer prices went up, but something else happened. The dollar becomes irredeemable after 1971. There is no longer a way to extinguish a debt. When you pay a debt after 1971, you pay a debt using dollars. It’s itself a credit. You’re paying a debt using a debt. You’re paying a credit using credit. You’re paying IOU using IOU, which means you don’t actually make it go out of existence. You simply shift it around. The total aggregate quantity of it necessarily goes up as a feature, not a bug of the system.

Necessarily goes up and necessarily goes up exponentially. The debt necessarily goes up exponentially because there’s no way to pay off a debt, only to shift it around. So that itself now causes a problem. So imagine everybody somewhere on the aggregate balance sheet, we’re accumulating debt that’s not any longer productive. It’s one thing if you borrow in order to finance a business, but at some point the asset that you finance, whether it’s a machine tool, a truck, the asset goes end of life. But the debt is lingering somewhere and that debt becomes increasing drag and increasing weight. So the problem is the debt is going up exponentially.

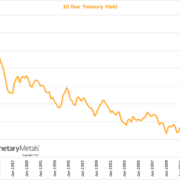

That would mean, should mean, that the interest payments, interest expense to service the debt should also be going up exponentially and that would quickly drag everyone in the economy to a standstill. It wouldn’t be possible to make a living or make a profit in business if the interest expenses going up like that. So initially interest rate was actually going up, but by 1981 the interest rates begins epic 40 year plus free fall. There’s some zigs and zags but you can see it’s practically a straight line down. Yeah, I get it, it’s up right now to 3% again, to put this in perspective, 3% is right here. So in terms of this epic fall. It isn’t much by any longer view, it isn’t very much.

So this magic trick is that by pushing the interest rates down then it makes the data more and more easy to service. Debtors should love this, right? Let’s say you owe a million dollars. If the interest rates is 10%, you have to pay $100,000 a year in interest. If the interest rates is 5%, you only have to pay $50,000.

The interest rate is 2%, it’s only 20 grand. See how that works? The interest rate has been falling for a very long time. Which raises the question. The theory says that interest rates should be at least proportional to inflation, so called, because otherwise why would anybody lend their money? Well, in an irredeemable monetary system, the saver is disenfranchised. There’s no longer a way to have money and not be a lender. I mean, even if you hold a piece of paper currency, I’m not exactly sure what the language says in the UK but in United States it says Federal Reserve note. Note is a word for credit. You’re extending credit to the Fed and the Fed lends to the government and the banking system to hold the money balance is to be a creditor. They got you and they don’t need your consent. And they don’t care about your opinion. And you might complain in the sense of whining about some stupid law that says you can’t produce domestic natural gas anymore, you can whine about it, but you have no say in the matter. You’re disenfranchised, there’s nothing you can do to change it.

You could buy gold or properties or whatever but then the seller is just taking your place. So they changed the name on the record of the banking system, nothing actually happens economically and life goes on. That’s how it’s possible to have an epic fall in the interest rate. If the savior’s preference had real teeth, then that would be stopped because when interest rates hit time preference, we can’t get interest rates lower then time preference because everybody redeems. Everyone says give me my gold back which forces the bank to sell a bond which pushes the bond price down and the interest rates is the seesaw, strict inverse. Bond prices and the interest rates are strict mathematical inverses. All that selling of bonds drives it up and that’s exactly what we should have in a free market. If you go to the grocery store and the price of steak is for some reason £200 sterling for 100 grams of steak, what are people going to do? I’m not buying that. The act of everybody not buying forces them to lower the price until the price will come to whatever the marginal steak preferences for people who are shopping, which is not going to be £200 sterling for 100 grams.

So the same thing should be happening here. But they’ve put a penny in the fuse box, they’ve disenfranchised the saver and now the saver is captive. Now, in the UK you sort of have negative interest rates on a few things but it doesn’t really go all the way out on the yield curve. In Germany and Switzerland they’re complete basket cases, it’s negative interest rates. Now, everything’s picked up a little bit in this recent bout but before this last thing in Switzerland it was negative interest rates from overnight all the way out to 50 year maturity, everything negative. So the system has got everybody captive or captured. Nobody has a choice in it and that’s how things can fall.

So you have the falling interest rates here as part of the positive feedback loop. Suppose you run Hamburger restaurant chain and you’ve got a spreadsheet which is your business case for building 50 stores all around the south of England and you have a business case to try to justify building the 51st store but it just doesn’t quite balance. So expenses are greater than net profit, so it doesn’t work. And then they come along and lower the interest rates.

Magic trick just like that to lower the interest rates and interest. Of course, interest expense is a major component of the expense of opening a store. You have to borrow a lot of money to go build out all of the fittings and fixtures and the tile and the stainless steel and all that and they lower the cost of money. So suddenly your spreadsheet clicks and then the red bottom line turns green and now it makes sense to borrow. So you open the 51st store because the falling interest rates essentially an increased, I would say incentive first, but also an increased subsidy to open that store. You and all the other hamburger chain operators. What happens with an increase in the supply of hamburgers? Unless the British diet changes to suddenly eat more hamburgers, what happens to the price of hamburger? False. The theory says increasing quantity of pound sterling should cause an increase in prices. But we see here there’s now an increase in supply with no change in the demand. We’re going to get a drop in the price of hamburgers.

Now the same thing is happening when the interest rates falls. That is universal. That’s not at interest rates just for hamburger operators. That’s an interest rates for everybody else. That’s an interest rates for everything from fish and chip places, to the companies that make the kitchen equipment, to the companies that make the glass that you put in the storefronts, to the companies that are raising the cattle and so on. Everybody has a drop in the interest rate. Everybody’s business case for expansion suddenly clicks green, everybody’s borrowing and expanding. Now, normally in a free market, the pool of lendable funds is not only finite but controlled by the savers. This sudden increase in borrowing demand would be self correcting. But in irredeemable currency, the borrowing is occurring because they push the interest rate down. And the demand for that fresh borrowing is only when the interest rates drops. When the interest rates ticks up, the demand for borrowing disappears. That’s the dynamic of why we’re in the falling interest rate. So the interest rate falls, you get an expansion of supply because it subsidized artificially by the falling interest rates and for no other reason. And so what you get then is falling margins is really what you get. That everybody selling hamburgers is now forced to sell at a lower price and so margin is just getting crushed, which has been the story of the past 47 odd years.

The Marginal Productivity of Debt

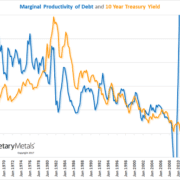

I really define the heat death of the economic universe is when marginal productivity of debt goes negative for the last time and that’s it. So what do I mean by that? A lot of people take a look at what’s the total debt in the economy? It’s not really that meaningful a number because what does that mean? Like how many people are there in the economy and how big is the economy? So then they might say, okay, well, you should divide data to GDP or something, but still isn’t really giving you a high resolution picture. What you really want to see is change at the margin. If you borrow a fresh new pound sterling today or fresh new dollar, how much does that add to GDP? Or state of the other way, how much GDP is added for each new currency unit?

This is based on the US. This is not government debt, by the way. This is total debt. This is loans, corporate bonds, consumer credit, government debt, everything all in and GDP all in. It starts out to add a dollar GDP for a dollar debt. Okay, that’s kind of interesting, but it’s falling until the global financial crisis, where arguably we’re at $0.10. So what that means is we’re getting a diminishing return. One way to look at this is it requires more squeeze to get the same juice, or the other way to look at it, as for the same squeeze, we get less juice, but there’s a diminishing return. What happens when that goes negative? We are obliged to keep borrowing because we have an irredeemable currency system. The debt is growing exponentially or else everything’s collapsing. But that is going up, but GDP is going down. It takes economic activity to support servicing the debt.

So when those two things are going opposite directions, debt is going up and GDP is going down, then that is completely unstable. That’s a thermonuclear. I guess the analogy I’m using is that the heat death that’s when everything comes to a finite end. So notice this isn’t like, okay, well, every ten years consumer prices double. This is we’re getting to a point where the thing cannot be sustained. And I don’t know if you have the expression here in the UK. Kicking the can down the road? So that can have a lot of kicks in it. That’s the thing that surprised everybody. A lot of people would have thought that by 2008 that was it, but they kicked that can and then they kicked it several times post 2008, and that can have a lot of kicks in it and probably has a bunch of kicks left in it even now. But this is saying that there’s a point at which there’s no kick left in it. The GDP is going down and debt is going up, and then what do you do? There is no there is no way out of that. You’re destroying economic activity with every dollar you’re borrowing. You’re obliged to be borrowing exponentially more dollars. That’s going to be the death of a literal death of a great number of people will perish in this. This will be a cataclysm. I don’t want to dwell too much on the negative. I’m not a big fan of doom porn, as it’s called.

What is GDP?

Okay, so what is GDP? I think GDP is production plus destruction. And so it gets the sign wrong. I mean, GDP is absolutely not just a wrong measure of the economy, but to use the term for Wolfgang Pauli, it’s not even wrong. You can’t add production plus destruction. It includes consumption, it includes capital investment. Those things don’t even belong in the same place. And then government spending on welfare programs are additive. What??

What’s the cash value of adding government expenditures on either useless programs or regulatory programs that actually impede production or pouring it down welfare drain? What is the purpose of having that be added to GDP and getting everybody and by everybody, I mean the people that try to advocate for capitalism in the free markets, business, Wall Street, the city, getting them all to agree on this definition?

And in the definition you smuggle the idea that government pouring money down welfare drain is additive to the economy. So it’s not GDP as such. Think about when you owe a debt. It’s not your gross revenue, it’s not your gross salary that enables you to service the debt. It’s the net. So out of your gross salary, first you take all the taxes, then you have to take out your cost of living, paying rent. You have a car, the Oyster card on the tube, whatever it is. Take all that out, whatever’s left, £100 a month, I don’t know, whatever that number is, all the debt service has to fit into that. So when you take out all the expenses and everything from revenue into profitability, all this borrowing is generating less profitability, which should be, again, very worrisome. It takes profit to service the debt.

Zombie Corporations

Every time I talk about zombies, I have to talk about the movie Broken Arrow, where they come into the president’s office and they say, sir, broken Arrow, sir. What the hell is a broken arrow? Well, sir, nuclear warhead has gone missing. He says, I don’t know what’s worse, that nuclear warhead has gone missing or that apparently happens so often you all have a term for it. The bank for International Settlements, not some fringe lunatic group on the Internet, but the central bankers central bank in Basel, Switzerland, has a term called zombie. And a zombie, I mean it’s slightly more complicated than this. But a zombie is a business whose profits are less than their interest expense, which means they have negative ability to service their debt.

So the rise in interest rates will push a lot of companies into this category who hadn’t been previously. Notice we’re already at 16%. Something like that. I’ve got other statistics. 20% of the SMP 500 stocks are zombies, something like that. So for zombies basically it’s terminal. It’s walking dead that is only able to walk because we’re pumping ever greater amounts of crack cocaine mainlining into its blood to keep it going. And obviously that isn’t sustainable.

Diminishing Returns

The point of this being that as the interest rates gone down, it’s an incredible incentive to borrow more. That borrowing more gets a diminishing return in GDP, let alone in profitability. But the debt remains like a hangover that lasts forever. Imagine if every time you drank whatever degree of headache, it’s like plus one on your headache meter like this is a video game and it never goes away. It only increments up. Obviously you shouldn’t drink if that’s how the world works. But it just gets worse and worse and worse. So we have this positive feedback loop situation. Interest rate falling incentivizes and encourages more borrowing, more borrowing to finance things that appear to be productive. But unfortunately it’s not just you that’s borrowing to add capacity, it’s all of your competitors.

So you get a diminishing effect even in terms of gross revenues, let alone in terms of net profit. And the whole thing is just sinking down. Down meaning margins, profits, debt service capacity. That’s what’s going down. Consumer prices going up. That’s the least of the problems here. Of course, this actually is the force for driving the interest rate lower. With the savers being completely disenfranchised. What is the one force that could drive interest rates up? A demand for borrowing by corporate enterprise. But as the corporate enterprise is sinking deeper into debt with lower margins, then their ability to demand more debt is decreasing and they only step up and borrow more when the interest rates comes down. Their new bid is falling. And every time the interest rates takes down, they’ll borrow more. Now the Fed thinks they’re going to hike interest rates. I think what’s going to happen is either they’re going to back away or they’re going to cause another 2008 style calamity. Only this one will be greater in magnitude because the imbalances are built up greater with the house of cards. We’ve added several more stories to that house. I like to use the analogy of something brittle. The economy become more brittle. One good whack of the finger and it shatters into a billion pieces.

So this is the heat death of the economic universe. Obviously there’s infinitely more to say about this, but I just wanted to present a thesis that there’s something that inexorably, inevitably leads to a finite terminus. It’s not ongoing forever, it’s not just okay. A simple linear function, double the money supply, double the prices. There’s something very pathological about this. The debt is a cancer and it’s eating the corpus economicus alive.

And this isn’t 50 years in the future. I don’t think anybody can predict exactly when. I don’t think anybody could predict first of all when that can will need another good kick, nor can they predict how many kicks are left in it. But clearly we’re getting close to the end here.

Questions

Thoughts on Modern Monetary Theory?

Yeah, it’s the Platonic ideal of there’s a few people that are imbued with some intrinsic, divine, revelatory powers and that’s why they have to put over the rest of us. To force us. This is the ancient old idea, not modern at all. Plato was what 2500 years ago, not modern in the slightest. And the same idea gussied up in a whole new package.

In order to keep people fed do we need to subsidize farming?

If the prices were skyrocket, then farmers would be able to make a profit. But stopping short of that for a minute, the whole picture I’m trying to paint is everybody, their margins are getting crushed. It’s not just farmers, it’s everybody else. Somehow we have an entire civilization which we enjoy a microphone with some really cool LED lighting in it. We have such wondrous technological things, right? And food is very plentiful and all these things and nobody makes much money producing any of it. We’re like on a treadmill frenetically running faster and faster and faster, producing more and more and more and more to get a diminishing return of a few pennies of margin out of it. And that’s the sort of cold death by drowning. It’s not the hot death by hyperinflation, it’s the cold death by crushing everybody’s margin, including the farmers.

Why are we having slower production?

Everything becomes more and more of a struggle. I think the reason why production of computers is getting slower is because of real problems in the supply chain which are caused by the lockdown and the whiplash of the unlock, not because intel or HP are yet at that point I think a lot of industries are. High tech will probably be one of the last industries because they have really strong margins. It’s everyone else’s margins are getting crushed to nothing.

What is the solution to all of this?

Solution? It’s amazing how often you find the solution is that you need a free market. In a free market you don’t have these one way ratchets without corrective. In a free market you have negative feedback loops. That is like the higher that the grocery store jacks the price of beef, the less buying you get because everybody is free to make their decision as to what they want to buy or not buy. And that freedom is corrective. You don’t get imbalances. But we have the opposite of a free market and money and it’s been that way for a long damn time. In the 19th century a lot of things are pretty free, certainly in America, but I think in the UK also. You didn’t need a lot of business licenses to open things. But banking has always been controlled. You need a money that enfranchises the savers. There has to be a real possibility to redeem your currency, force the banks to sell the bond and raise the interest rate and obviously that’s gold. But this talk isn’t really about promoting the gold standard as such. It’s really just talking about the pathology of this cancer ridden system with the antidote it’s a free market.

So do you reject the Quantity Theory of Money?

I make a distinction between monetary and fiscal. So monetary is the bank of England buys some guilts off of the banks and gives them reserves in exchange. That’s a monetary policy which drives up the price of the guilt, which drives down the interest rates. And so you end up with some monetary changes. Versus her exchequer, I guess you call it, gives everybody a stimulus check of £1000. So free money to go spent, which I would call fiscal.

Is there a fear over how much gold the United States has?

We’re speaking for the United States. I think the assertion is there has not been an audit gold specifically, or I guess the stock take of the gold specifically, since, as in our administration, I believe the Fed itself is actually audited. The problem with this stuff is that it’s a massive undertaking. It’s very complicated. I mean, a certain sense who could oppose? The government owes us accountability. They work for us in theory. Who could be opposed to holding the government accountable? Who could be opposed to an audit of the government laying bare and shining sunlight as a disinfectant on everything they do? But I think if you publish the audit report for the Fed, it’d be 100 million pages of accounting stuff, that only an accountant specializing in government accounting could even read. And then, of course, every side is going to declare victory because then they could cherry pick something that either actually supports their side or they misunderstand or misinterpret it, and then they believe it supports their side, and everyone declares victory and goes home and what have you accomplished?

You got to get rid of this damn central planner. I don’t think the government should be in the business of owning gold or any other asset frivolously anyways. I mean, the government needs to own some army bases and some police stations and some courthouses. The legislative House of Parliament has some basic properties that it needs to own, but if it owns property all over the place, that should all be liquidated. And the same thing with owning gold. What is the purpose of all that? Is there any irregularities there? I don’t know. Maybe. I think in the West there probably isn’t the kind of simple, obvious criminal fraud that people in dark corners of the Internet like to allege. The West doesn’t operate that way yet. There isn’t a culture that excuses or justifies fraud like the people that commit fraud have to hide under a rock. It isn’t generally accepted. It’s not like Argentina. It’s not like even, I think, China. It doesn’t work here. Most people would be repulsed by it. And so what I would expect is you wouldn’t find that kind of regularity. Would you find mistakes that compound over a long period of time? Would you find other questionable transactions, perhaps? Who knows? Probably. Maybe. Okay, so you find that then what I guess becomes the next question anyway, what are you going to do? Unwind the transaction, go to the counterparty, force them to plot back? I mean, some of these things are probably decades old too. So as a practical matter, I don’t know what good it really does or who’s really accountable for anything anyway.

I think the key is to just make a clean break and say, okay, going forward, let’s handle this properly. Not having the government centrally planning anything and not having the government just owning what is it? It’s a couple of hundred billion dollars. In the case of the United States, a couple of hundred billion dollars of gold? Why? Sell it, be done. You stole it from the people. It’s now three or four generations after those victims. I don’t know if there’s any way to really identify the rightful owners and return it. Too much time has passed. Just sell it. It’s gold. It has a market value. Sell it and be done.

How do we move to a free market in money, with the least amount of shock?

That is a nice segue for a paper that I’ve written in another talk. So I talk about The Dollar Cancer and the Gold Cure.

And the dollar cancer is kind of a different view of this. It’s all the same system, obviously. I’m just trying to tease out and look at different aspects of it, make them more comprehensible. The gold cure is the key is to remonetize gold. And the key to that is that gold has to be investable to earn interest, which happens to be what my company is all about. At Monetary Metals we pay interest on gold by investing it productively, not by sticking it in a vault and betting on its price to go up. And when the price goes up enough, then you sell it. That’s not a gold standard, that’s just treating gold like artwork or antique Ferraris. It’s just something you buy for the price to go up and then sell it. It has to be financing productive enterprise in gold and people have to be earning return on their gold in gold. And when you’re doing those things, you get a graceful transition to the gold standard and a bottom up entrepreneurial free market approach, not the government declaring the gold price is henceforth is going to be $2,000 an ounce or whatever, but an organic process that goes there.

And I think the question kind of implies, and I agree, if we don’t go there gracefully and organically, we’re going to end up there in a very cataclysmic sort of way. But things will collapse and then at that point, obviously, all the paper currencies will be wiped out. Gold will be the only thing left standing for the few survivors that emerge from whatever dark age ensues. Yeah, they’ll be using gold again, but that’s a small comfort to those that live to see that day.

Why is the interest rate falling?

So that get’s into my theory of interest in prices. So it’s another ratchet effect positive feedback loop with resonance system. With free people in a free market you have two spreads. So there’s time preference which is kind of part of the nature of being a human being. Mises calls it originary interest. I think there’s some intrinsicism overtones to what he’s saying. But to be a human being is to value a bird in the hand versus the promise of a bird one year from now. So there’s time preference and if you’re not going to get a certain interest rates to compensate you for the time, let alone the risk, just the time, then you might as well have the gold coin in your hand and not be a creditor. Then there’s the market rate of interest which has to be greater than or equal to time preference or at least marginal time preference because if it ever gets to that point the marginal saver is withdrawing their gold which is forcing the interest rates up and so it will always be greater than equal to that.

And then finally you have return on capital. Marginal productivity of the entrepreneur. As the entrepreneur you can’t borrow at 10% to finance a hamburger restaurant that gets an 8% return on capital. And so if the interest rates were to go to 10%, you certainly would get a cessation of all opening of new hamburger restaurants. You might even get liquidations depending on whether they borrowed a variable interest rate or fixed interest rate. So there has to be two positive spreads. Time preference to market rate of interest and market rate of interest to marginal productivity. Both of those have to be positive spreads. Saying I’ve got some dollars, you got some gold, let’s trade. It has no monetary effect. It has an effect on you personally obviously, but not on the monetary system.

Do you think continuing on with subsidies is our best worst option?

No. I address this question head on in my dissertation. I talk a lot about gold and backwardation and all these things but I think probably the most important thing I said in my dissertation is that the government has a dozen or more different ways they can interfere in the economy. So they can set a price floor, they can set a price cap, they can set a subsidy, they can set a tax. All kinds of things they can do. And always the promise is we’re doing this to improve the outcome. You idiots in the free market are selfish and stupid and you’re going to mess it all up. You are messing it all up for yourselves. We will do good to you and make better outcomes, which in economic terms means we will solve the coordination problem and make you coordinate better than you could ever figure out in the free market on your own. That is the promise always. Otherwise nobody would vote for it. The promise is we’re going to improve coordination. And in one sense you could say economics is the field that studies coordination. If it’s one person alone on the desert island, there’s no field of economics.

You start to have people that are coordinating get division of labor and specialization, comparative advantage. A term, I think coined by Adam Smith or at least used by him. And people begin to sort themselves out into an economy. What I proved in my dissertation by looking at, I think, ten or eleven different cases, is that in every case of government intrusion in the economy, leaving aside they professed good intentions, leaving aside the bogus Platonic philosophies, in every case and I proved this scientifically, I think Ayn Rand in objectivism, gave a moral underpinning why people should be free. But I looked at it economically and proved, using what I call the calculus of spreads, that every time the government intrudes necessarily and always, it causes a reduction in the ability of people to coordinate or an increase of discoordination. Whether that’s a protectionist measure, a tariff, a ban on imports, a ban on immigration, whatever it is that they’re going to do. Necessarily and always makes it worse while they’re promising loudly propagandizing how much good they’re doing to you by doing all this. When you observe people making this promise and then their actions are producing the exact opposite outcome and the more that their actions produce the opposite outcome, the more loudly they proclaim their intentions you can tell they’re not honest. The people that are doing this have to be aggressively indifferent at best to the outcomes they’re causing.

A simple example suppose you set the minimum wage at 100 lb/hour. What would happen? Anybody? What would happen if the wage was set by statute, by law it was a criminal act to hire somebody and pay them only a mere £99 sterling per hour? What would happen? Everybody gets laid off. The end. So all they’re doing, they can’t make the payment of something more than it’s worth. All they can do is outlaw the transaction altogether. So what you observe then is huge numbers of layoffs, I guess you call them furloughs here. And whenever you see there’s a group of people over here who want to sell something, in this case labor, and a group of people over here who want to buy something. And somehow these two groups cannot get together. Cannot coordinate if I were to use that term. There’s some force that was holding them back that force is literally government with a gun force that’s the thing that’s holding people away from coordinating and if the government got the hell out of the way then the labor market would clear there’d be no such thing as unemployment as such. Not at a wage of 100 lb/hour but whatever wage it cleared and everybody has a job. Everybody wouldn’t be as rich as they want to be but the government can’t create that wealth all they can do is criminalize low value work.

Explain the credit inequality between small businesses and large corporations?

Yeah that’s a very interesting observation. So even in normal times in a free market a major corporation will have more access to credit cheaper than a mom and pop store or startup. Obviously they’re more credit worthy. Picture a swimming pool where the level of the surface of water is of course flat. Underneath is a slope and the mom and pop small businesses and early stage companies are on the shallow end and they don’t get a lot of credit and maybe even there’s little waves of credit that lap and they can just get a taste of it and the major corporations are in the deep end and they get what they need. But when the central bank, you want to talk about non neutral, it’s not pushing it down evenly like an old cast iron platinum on a printing press with two giant steel posts. That thing absolutely has to move down evenly because if it moves down 1 mm more on one side versus the other the mechanism jams it won’t move at all. No. This is more like on some sort of amusement park ride that as they push it down actually they’re pushing this side down and this side is going up. There’s like a hinge or pivot in the middle and they’re actually stripping the credit out of this end and making it harder for them not necessarily raising the interest rates but making the credit less available. Harder to obtain through a variety of different mechanisms. Higher underwriting standards. Banks are simply not pursuing that segment in the first place.

More compliance and paperwork and all sorts of stuff to go through because the regulators are trying to supervise the banks in what’s called macro potential regulation. And when there’s so many different mechanisms, they’re steering the banks away from this. So these guys are absolutely drowning, flooding in lot of oceans of dirt cheap credit. I call it credit effluent. I mean, it isn’t healthy for them. It’s effluent. It isn’t good stuff, but they’re drowning in oceans of it. And these guys are high and dry. Right? So I call that the credit gradient. And as they lower the interest rates, the credit gradient becomes steeper. And, yeah, that’s a very good example of non neutrality, of money and monetary policy.

Make sure to subscribe to our YouTube Channel to check out all our Media Appearances, Podcast Episodes and more!

Additional Resources for Earning Interest on Gold

If you’d like to learn more about how to earn interest on gold with Monetary Metals, check out the following resources:

In this paper we look at how conventional gold holdings stack up to Monetary Metals Investments, which offer a Yield on Gold, Paid in Gold®. We compare retail coins, vault storage, the popular ETF – GLD, and mining stocks against Monetary Metals’ True Gold Leases.

The Case for Gold Yield in Investment Portfolios

Adding gold to a diversified portfolio of assets reduces volatility and increases returns. But how much and what about the ongoing costs? What changes when gold pays a yield? This paper answers those questions using data going back to 1972.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!