Why Do Investors Tolerate It, Report 17 Dec 2018

For the first time since we began publishing this Report, it is a day late. We apologize. Keith has just returned Saturday from two months on the road.

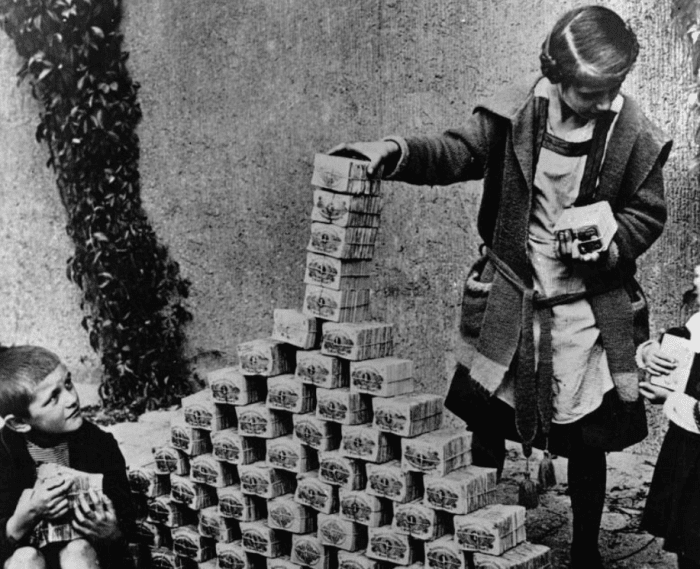

Unlike the rest of the world, we define inflation as monetary counterfeiting. We do not put the emphasis on quantity (and the dollar is not money, it’s a currency). We focus on the quality. An awful lot of our monetary counterfeiting occurs to fuel consumption spending. And much of this, certainly a very visible part of it, is government borrowing to pay for the welfare state that is not supported by taxation.

There are four components to our definition of legitimate credit:

- The lender knows that he is lending

- The lender agrees to lend

- The borrower has the means to repay

- The borrower has the intent to repay

It is counterfeit credit, if one or more of these criteria are breached.

If the government cannot pay current expenses out of tax revenues, then obviously it can never amortize its debt. So this shows the Treasury bond itself to be counterfeit credit. But let’s consider the dollar.

The funny thing about the dollar, it is universally regarded to be money. This is no mere dispute over definitions or semantics. It means that people who hold dollars deny being lenders! They do not believe and would not agree if you told them that they are creditors, financing profligate welfare-state spending. The dollar is base money, end of story. Well perhaps not end of story, if push comes to shove. Yeah, the Fed accounts for it as a liability but since it’s not repayable, it’s not really a liability. And so on.

So the lenders cannot know that they are lending, as a definition neatly forecloses on this knowledge. Or admitting to having this knowledge.

Anyways, borrowing to finance welfare spending is covered under #3. Let’s consider a different case. It is when corporations sell a bond to finance a capital asset. Perhaps they are acquiring a profitable company. Or maybe they are building a new plant.

Corporate bonds today are often non-amortizing. They pay interest only, with a balloon payment at the end to return the principle. How do they plan to pay? Either they must sell more shares (raise equity), or else they must sell another bond to repay the first bond.

Obviously, this exposes investors to the risk that the market will not let the company sell equity or debt at the time when the bond matures. From where we sit today, after nearly a decade of endless bidding up of assets, this seems a remote risk. But 10 years ago, the market was closed and many companies were forced into bankruptcy as they were unable to pay debts when due. Including the acquirer of Keith’s previous company, Nortel Networks.

So this leads to a question: why is it this way? Obviously, a non-amortizing bond puts less pressure on borrowers’ cash flow. The borrower is not paying the principle. So of course borrowers prefer it. But why do investors tolerate this?

One reason is that it’s easier. The principle is not dribbled back. Picture an institutional investor who deployed $10,000,000 in a bond. It has the entire ten mill working for the entire 10-year maturity. If the bond amortized principle, the fund manager would have to work harder to deploy the principle that came back every payment period.

And of course, in a chronically-falling interest rate environment, if you buy a bond that’s yielding 6%, then you do not want to get some of it back and be forced to start buying bonds at 5.5%, then 5%, then 4%, etc. You want to lock the full ten million for 6% for the full 10-year maturity.

Does a non-amortizing bond signal the issuer’s breach of #4, lack of intent to repay?

This leads Monetary Metals to a dilemma, as we bring gold bonds. A future gold standard, if we are to have one, must be based on monetary integrity. If we are not to have integrity, if we don’t choose to have it, then we have no need of gold. Irredeemable paper serves the purposes of monetary counterfeiting just fine…

So the question we face is this. Should gold bonds be amortizing? If they’re borrowing to finance construction of a mine with a 20-year expected life, should the bond be amortized in 10 years (or less)? Or if they’re financing a vault or a refinery or a jewelry production line, should the bond be amortized in no more time than the business plan projects profits for the asset?

Or should the first gold bonds be designed meet investor (i.e. institutional investor) expectations? Expectations that were set in today’s world.

There is one other investor advantage to an amortizing bond. It reduces the exposure to the risk of default. Any principal that is repaid, is not lost if the issuer declares bankruptcy.

We would love your feedback. Please contact us with any thoughts you have to share. Thank you.

Supply and Demand Fundamentals

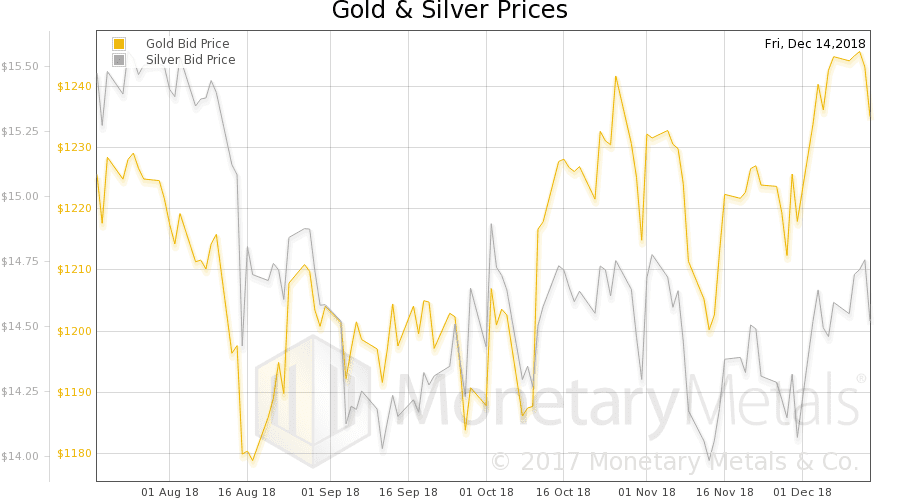

This week, the price of gold was down ten bucks and silver four cents.

Someone on Twitter demanded if we didn’t find it odd that the biggest sovereign debt bubble has managed to inflate a bubble in virtually every asset price except for gold. Given that he went on to assert there is a bubble in paper gold claims, he is trying to say that gold has to be suppressed. Otherwise its price would be much higher. We won’t reiterate here the proof that this conspiracy theory is false.

Instead, we want to address two points. One, the term bubble is used quite flexibly. Does it mean the price of something is too high? For example, the S&P Index at nearly 3000. Or does it mean there is too much quantity of something, e.g. debt. Or that something is being done to unhealthy degree, e.g. sending non-students off to university to get degrees that will not increase their employability? One should use each word with care and precision. Otherwise ambiguity permits one to migrate freely between different concepts.

Clearly, this guy is jealous that the prices of other assets have gone up, making other speculators rich. But the price of gold has not, thus not making him rich. Instead of admitting he was wrong to believe the gold-to-$10,000 story, he blames the world. Also, he is wrong about something else. The price of oil has not exactly gone up. Or real estate in many non-trendy locations.

But that’s not quite our point. We think it’s important to understand that prices of things do not go up in an automatic way, as many take the quantity theory of money to imply. Prices go up when buyers are aggressive and sellers are reluctant. Whether or not an increase in the quantity of the counterfeit paper that is yet called money causes this, we leave to another day. But even if so, this would obviously be a two-step process. Step one is increase quantity. Step two is when many people take their surplus free cash and trade it for assets such as gold bars.

And even that is not quite right. There is no such thing as a helicopter drop of free cash. There is lending, perhaps at near-zero interest (in the US—in some countries, below zero). Would you borrow money to buy gold? You can, you know. It’s called margin. You can buy GLD with 2:1 leverage, or a gold futures contract with 10:1.

But people don’t do this casually, as leverage increases risk. They do this only for assets that are going up. We have already established that gold is used by people like our Twitter interlocutor for one thing. For betting on its price. We don’t know his portfolio, but we would bet that even he is not betting with leverage right now. It’s much easier—and less risky—to complain that others aren’t betting with leverage. I.e. driving the price up so he can sell and make profits in dollars.

He does not conclude that every asset is like the planchette of a Ouija board, moving around as speculators shift their preference. And instead of concluding that the price of gold is really just the mirror of the price of the dollar, which is strong right now for readily visible reasons, he feels hurt.

And he does not think through that if gold were useful only when it went up, then it would be useless for any other purpose (one of our main criticisms of bitcoin), and hence its price would move all over the place. Including downwards and sideways. And only begin moving up again, when all the frustrated speculators like him finally capitulated and sold off their gold. Then, unloved and neglected—not breathlessly anticipated by a whole sector full of self-declared contrarians—it would finally begin a stealth bull market once again.

Of course, the whole point of our extended bout of snark today is that this is not so! Gold does have uses other than betting for dollars.

Gold is the once and future unit of finance.

There is a way to analyse the likely price direction of gold. It’s not to buy into stories, even true ones much less manipulation conspiracies. It is to look at the basis, the spread between spot and future prices.

So let’s look at the only true picture of the supply and demand fundamentals of gold and silver. But, first, here is the chart of the prices of gold and silver.

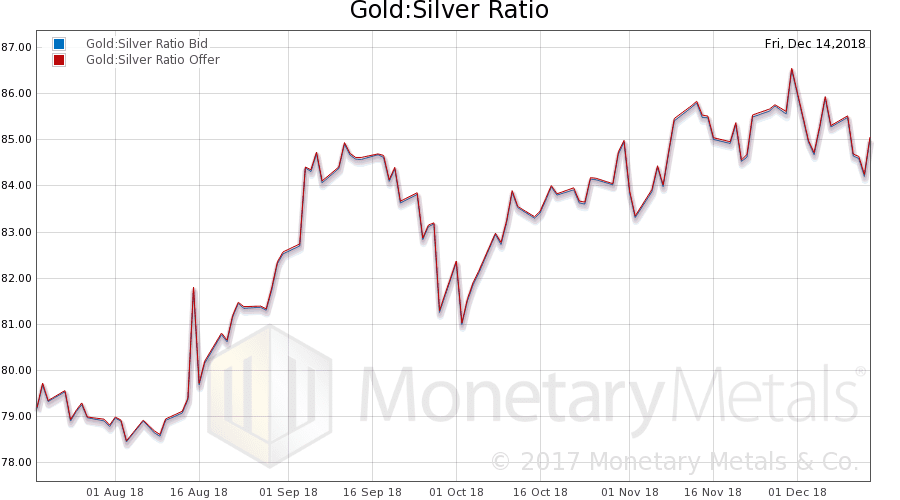

Next, this is a graph of the gold price measured in silver, otherwise known as the gold to silver ratio (see here for an explanation of bid and offer prices for the ratio). It fell this week.

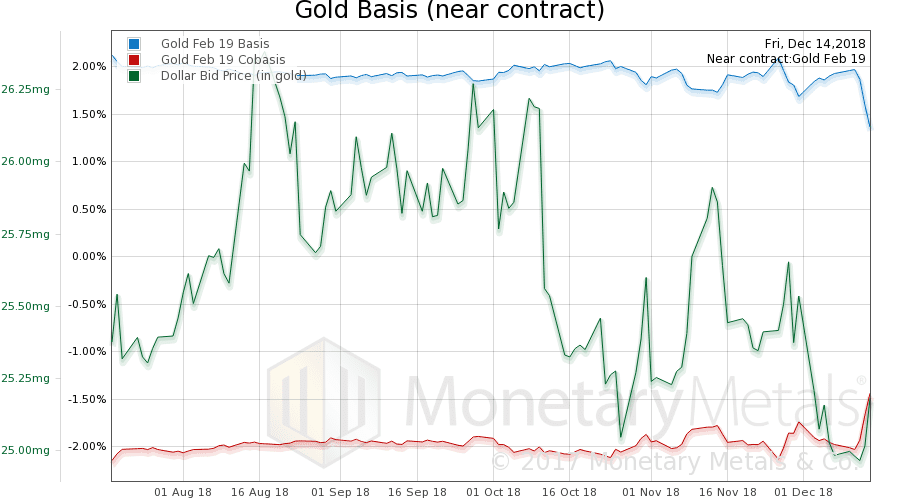

Here is the gold graph showing gold basis, cobasis and the price of the dollar in terms of gold price.

As the price of the dollar rises (inverse of the price of gold, which fell), we see a rise in the scarcity of metal (i.e. cobasis).

The Monetary Metals Gold Fundamental Price fell another $5 this week to $1,288.

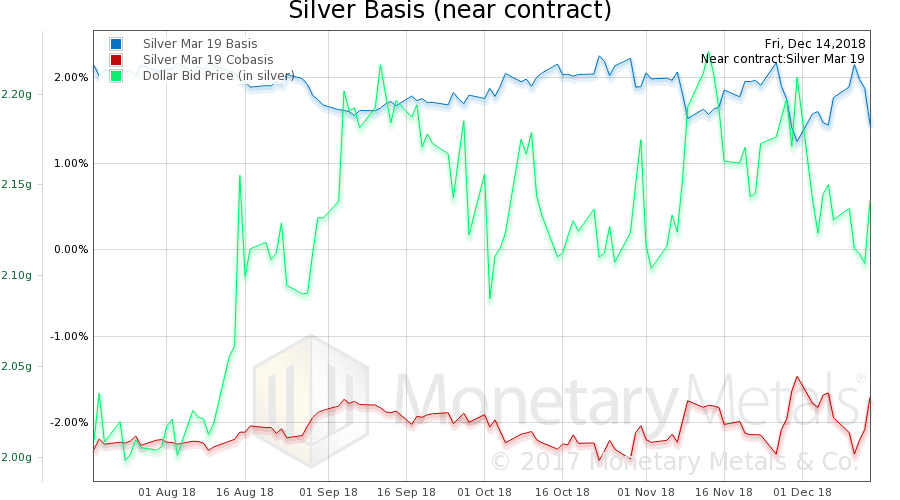

Now let’s look at silver.

In silver, we see the same pattern.

And unlike in gold, the Monetary Metals Silver Fundamental Price rose 8 cents, to $15.14.

© 2018 Monetary Metals

In response to your question, I suggest that a good gold bond design would be non-amortizing, but with relatively short duration, like 3-5 years, with options for both lender and borrower to roll over to another term. You can make the offering more favorable to the lender by locking in the rate for 15 years, say, with an option every three years. Or, reverse those terms to make it more attractive to the borrower, if you like.

Sounds almost like a dividend or a long-term lease agreement. Personally I’d call a perpetual loan an investment, more like a I was holding a share, precisely because I’m exposed to higher risk of default. The terms depend on lender & borrower expectations and then hash out something that runs down the middle.

Prior to 1933 gold bonds were commonplace. I’m not informed about how they were structured but wouldn’t they serve as a model for gold bond issuance nowadays? As a potential lender via a gold bond, I think that I would want the bond to be self-liquidating – i.e. to have a fixed maturity rather than to be perpetual. U.S. Treasury-bills, -notes, and -bonds are primarily defined by their maturities with T-notes usually considered having a maturity out to as much as 10 years. I’m not sure if your gold bond would fall into the notes category or the bonds category; that might be up to the terms that both borrower and lender agree upon. Given present day financial conditions, as a potential lender to a commercial borrower I think I would want my principal back no later than 10 years although I understand that institutional investors might be comfortable with a longer time frame. A question: does your “yield on gold paid in gold” mean that the bondholder receives periodic interest in gold or that the interest is paid in full only at the time of maturity?

Today’s credit markets are unusually liquid. Amazingly so. What most don’t remember, however, is that “liquidity is a chicken”. At the first sign of real trouble we can expect credit market liquidity to dry up almost instantly. First, lending standards will tighten… and if things deteriorate further banks and other intermediaries will simply shut off access to all but the most credit worthy customers. That’s the way it always is. In fact, if is wasn’t for the “Greenspan Put” or the “Bernanke Put” (and the promise of “helicopter money”) I believe things would have already changed.

In other words, the next good recession/depression will end this perpetual bond nonsense. (But alas, “today is not that day”) Today, the party continues.

As an example of credit market changes that are possible, consider what happened to the mortgage market back in ’07 – ’09 Defaults started, credit standards tightened, down payment requirements increased, and so on. You see, as the real estate market dropped we were reminded once again that “liquidity is a chicken!”

But that was just one sector. NOW imagine a world where the financial stresses and defaults are widespread, and world wide.

Would that change things? You bet. What if the entire planet slowed down? Let’s say Europe slowed first (happening now) and then the emerging markets, and Asia… then the U.S. Is there never any concern about repayment? That’s crazy… we’ve been spoiled by access to virtually unlimited credit. Phony credit at that!

As a lender, I vote for amortization. It’s like a dividend. If a company doesn’t have sufficient cash flow to pay me a dividend, something’s wrong. A principle payment tells me that everything is going reasonably well.

As a borrower, sure, I’d vote for no amortization! It’s a matter of self-interest.

My perspective is obviously old school. Don’t like it? Then tell me, how’s the new school been working out for ya? You know…. the school of thought that has lead the entire country if not the entire world into bankruptcy? Yeah, that one. So I’d say the old school is looking pretty darn good right now.

I’d expect a vibrant gold bond market to offer a range of products, callable and non-callable bonds crossed with both amortizing and non-amortizing instruments. Each prices a different credit/risk assessment, but only the non-callable, non-amortized, bond with (quarterly) coupon interest payments and principal due at maturity is the “pure” product. You can model all the others as compounds (ladders) of pure bonds.

That said, the business model and its maturity will determine how its credit risk should be priced. In the case of a nascent gold bond marketer, the primary hurdle is to establish the best possible credit reputation so as to drive the bond yield down to the desired long term borrowing rate for the enterprise when running at optimum (business maturity). Since in Monetary Metals situation the market is rather small and will be ‘feeding’ off of repeat business until it can grow its financial market share, I’d think amortizing bonds fit the picture best (or what would be equivalent, a yield-curve across various durations, with very little long-term borrowing at first while you must pay higher yields to compensate the risk long term lenders take in a new enterprise).

The answer will always depend on the circumstances of each bond issuance, and for the first many rounds, a lot of information is being conveyed and market structure being formed. The higher yields are the borrower’s price for building a credit reputation. As that gets built it changes the circumstances of subsequent bond issuance. Plan to succeed.

One further thought: I just read the tax reporting rules for amortizing bonds (the return of principal denominated in gold is likely to incur a dollar-denominated capital gain/loss component in the tax treatment of the proceeds). For that glitch alone, it may be best to let the buyer structure a ladder if (s)he’d like something that recovers principal stepwise over the life of the bond(s).

Gregory: it would not be treated as a return of principle?

Yes, it certainly should be that simple; if the bond was purchased with a gold transfer or the bond’s gold principal was purchased with dollars, it should retain its basis cost and the taxable gain or loss would only be realized when it is traded for dollars. Still, in the case of an amortized bond, the (gold) interest probably needs to be reported as a dollar amount of interest paid and you’d need to separate out the (gold) principal-return portion. The bond owner may also have to track basis across a more complex portfolio.

Suppose an amortized gold bond has returned half of its principal and is then sold (in either gold or dollars) for a capital gain/loss vs the bond purchase basis minus the returned principal. A gain/loss denominated in gold is a capital return on the bond asset, what is the basis of any new or remaining gold in one’s portfolio? Does realizing a gain/loss on the sale of the bond (for a new amount of gold, presumably) change one’s per ounce basis? It seems that these distinctions would matter if gains and losses on gold buliion are taxed at a different rate than similar gains or losses on the securities derived from the bullion.

I am certainly no expert, nor any friend to taxing authorities. I also don’t think it would be wise for Monetary Metals to proffer tax advice. But it’d be nice to have an overview of how tax law has historically applied to these topics. I just observe that amortized securities pose relatively more complex accounting for the basic transactions.

As you must know, gold bullion is taxed as a “collectible”, so that long-term capital gains do not qualify for a 0% rate bracket (if your marginal rate is 15%) and are always taxed at your ordinary income tax rate up to a cap of 28%. This applies to bullion ETFs also, but not to derivatives in the gold futures markets.

As a “security’, a gold bond should be taxed like an ordinary dollar-denominated bond (or perhaps a better analog would be a bond in some other non-dollar currency). I’m just trying to tease out which parts of a gold-denominated bond contract transaction will be current ordinary income and/or current investment income and which parts would be sales or purchases of a collectible. I’ve been assuming that coupon payments made in gold are current ordinary interest income reported as dollar amount at the exchange rate prevailing on the coupon date–that amount then being one’s basis in the new collectible asset lot.

I suppose there could be another taxing model, where payment made in gold is not current income, but rather just a non-taxable stock dividend wherein you’d lower your basis per ounce held and wait to realize the (dollar) income until the collectible is sold. That should lower the tax rate on the coupon payment for anyone above a 28% marginal rate and also defer the tax until the gold position is sold (when hell freezes over). Somehow I think that accounting would need special dispensation from the IRS ;-).

Thank you. Great comments!